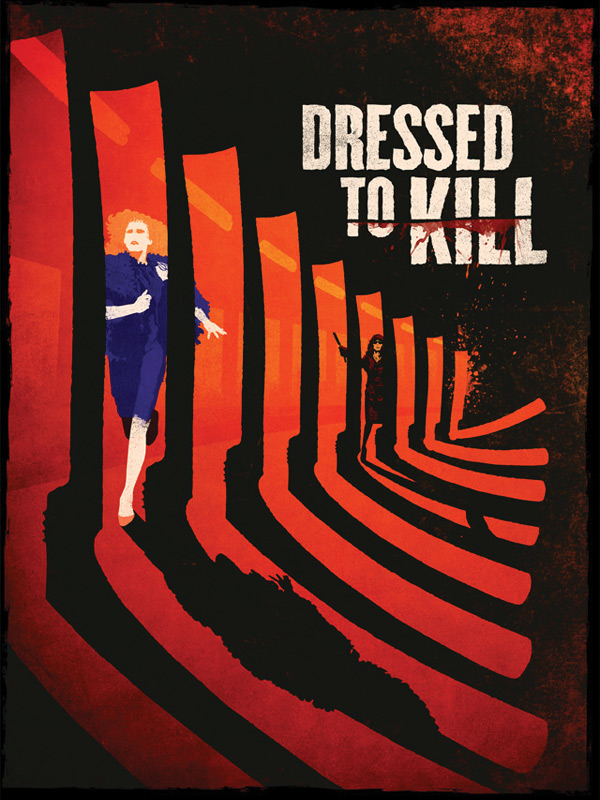

Depending on whom you ask, Brian De Palma’s 1980 thriller Dressed to Kill is either a brilliant reworking of Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) or a cheap style-over-substance rip-off. From IMDb message board shouting matches to painstakingly nuanced scholarly reappraisals, the debate (as part of a larger one regarding De Palma’s body of Hitchcockian films) survives in one form or another 35 years later. Yet what interests me, having viewed Dressed to Kill for the first time only recently, is the relative (not total) and conspicuous silence surrounding what should be a more important cinematic appropriation: the film’s representation of transgender identity.

At the risk of flattening some of the genuinely interesting and complex commentary the film may be making about gender (see Sam Krowchenko’s recent post for a thoughtful reflection on this)—and at the cost of spoiling the plot—the most important detail for the present occasion is that Dressed to Kill is a murder mystery in which the killer is revealed to be a “transsexual” psychiatrist “about to make the final step” but whose “male side,” his own doctor explains to the police, “couldn’t let him do it.” “There was Dr. Elliott,” he goes on in a scene called “Sexual Pathology 101” on the DVD menu, “and there was Bobbi…. Opposite sexes inhabiting the same body—the sex change operation was to resolve the conflict. But as much as Bobbi tried to get it, Elliott blocked it. So Bobbi got even,” the doctor says, gesturing expertly with his pencil, by killing a female patient who has aroused Dr. Elliott’s “masculine self.”

Dressed to Kill is hardly the first movie (and certainly not the last) to play off of and perpetuate transmisogyny—remember we’re talking about a riff on Psycho—which unfortunately may have to do with why so few viewers are remarking on the fact. Indeed the film participates in an even more specialized tradition of harmful representation. “[P]eople have always used horror stories to work out their fears around gender,” says Malic White in a Bitch Magazine article. “For years the ‘transsexual killer’ trope has haunted the trans community with a bad reputation.”

Yet it’s not the sheer repetition of this trope alone that has naturalized it to that large portion of viewers whose only complaint about Dressed to Kill is that it’s a pale imitation of a masterpiece. Perhaps more pernicious to my mind is the fact that these misrepresentations come packaged in the subtle and immensely powerful argumentative logic of narrative—and cinematic narrative especially, which invites us to sit back and consume so passively. The pleasures of stories, foremost the cause/effect movement of plot and the emotional investments we make in characters, can also be distractions that make us susceptible to mistaking subjective fictional representations of reality for reality itself. The fictional world seems so true, its events so inevitable, we tend not to realize we’re being subjected to an argument at all. There’s a reason John Gardner’s famous analogy likens successful fiction to a “vivid, continuous dream,” where we forget what we’re reading is actually artificially constructed.

In another post, I described my resistance to the narrative argument I found in Damien Chazelle’s film Whiplash, that the true path to artistic accomplishment is ruthless, selfish dedication. This is the idea Chazelle’s protagonist jazz drummer, Andrew, puts forth and the method he pursues; the film’s triumphant climactic scene eventually “proves” him right, and thus his dangerous and clichéd idea true. Narrative logic works in other ways, too, for example by omission, caricature, or tokenism—see this Salon article on “the overwhelming whiteness of Boyhood,” or “Why Are All the Cartoon Mothers Dead?,” an Atlantic essay that interrogates a disturbing trend in animated children’s movies, where “the creator” is given “total omnipotence.” And despite—no, because of—how trivial and entertaining narrative may seem, it really is powerful. Shakespeare wrote The Merchant of Venice over 400 years ago; in college I met someone whose parents had named him Shylock, so that he might redeem the evil name.

Because narrative can mislead us this way and because so many films have represented transgender identity so irresponsibly, “for many viewers of these movies, these characters have been their only pop culture reference points when a trans* woman is mentioned,” suggests this Autostraddle piece. “That means that when they hear that someone is a trans* woman, they have a list of characters that are lumped into this general category of ‘women who are really men’ and that category is filled with psychopaths and serial killers.”

And while Dressed to Kill probably isn’t anyone’s favorite movie (Bitch categorizes it as a “bad B movie”), the popular success of certain household-name classics, say Psycho, again, or The Silence of the Lambs (1991), “makes them perhaps more dangerous for trans people. Because they are so influential and so many people see them, they help widely spread the idea of the ‘scary transsexual.’ The characters in the movies are icons of American film. It could easily be argued that Norman Bates and Buffalo Bill are two of the most famous trans* characters in all of pop culture. It’s dehumanizing to realize that when you tell someone that you are transgender, there’s a good chance that the first people that will pop into their mind is the villain from a horror movie.”

And while De Palma’s Dr. Elliott or Bobbi may pop into fewer minds, Dressed to Kill’s narrative logic is no less sly or effective. The movie predetermines the revelation of the killer early on, when in the absence of his female receptionist, Dr. Elliott must do her job, playing two gendered roles: “Go right in,” he tells the patient he—as Bobbi—will soon kill. “The doctor will be with you shortly.” The revelation itself offers all the satisfying finality of a truth, presented as not simply the solution to the problem driving the film forward but the only solution, the only answer that makes sense given the logic of the plot. Of course! we say, even more pleased if we’ve outsmarted the movie and guessed the ending ourselves.

In the “Sexual Pathology 101” scene, we’re put in the point of view of a female character out of the know, allowing the film, through the doctor, to “teach” us. “What’s wrong with that guy, anyway?” she asks the doctor. The answer: “He was a transsexual.” And as he answers, the doctor—the actor playing the doctor—looks like a doctor, he sounds like an authority. And in the very next scene our newly enlightened point of view character, now with the air of an expert herself, passes on what she’s learned to a curious teenage boy—as if the film were mimicking the very process of misinformation in which it participates itself.

I have to wonder what I would have thought of Dressed to Kill not long ago, before my own continuing education about the transgender community as well as the growing Internet attention and awareness. As a straight cisgender male it’s my privilege not to notice or be hurt by these kinds of phobic misrepresentations (or any, really). Would I have woken to see the fictional dream for what it is—a fictional nightmare?