It’s April 2012 in Chicago, and I’m riding the el train with Bruce Lack and another friend from graduate school, Dan. We’re in the city for AWP, headed to a restaurant in Humboldt Park—Borinquen, home of the jibarito sandwich—when Bruce begins describing to us a movie, a 2005 British horror film called The Descent. If you haven’t seen The Descent, let me catch you up with a quick plot summary from Wikipedia: “The Descent … follows six women who, having entered an unmapped cave system, become trapped and are hunted by troglofaunal flesh-eating humanoids.”

These troglofaunal flesh-eating humanoids, also known as “crawlers,” scuttle about underground Appalachia in search of nubile young spelunkers to devour. Director Neil Marshall draws inspiration for his thriller from The Thing, Deliverance, and Texas Chain Saw Massacre, a combination resulting in the sort of good old-fashioned fun that makes you rock yourself to sleep in the fetal position afterward. Bruce, recounting the movie on the way to dinner, is no miser when it comes to narrative detail: he delivers intricate character histories, above-ground and below-ground double-crossings, and of course there’s the epic, climactic battle wherein Sarah, the main character, “goes hard”—meaning she gives herself over to primal instincts and brute strength in order to defeat a gaggle of bloodthirsty crawlers before scrambling to safety atop an impressive Ben Bulben of human bones.

If The Descent doesn’t sound like your cup of tea, let me stop here and say this: I hear you, I really do. Some of us can barely get through reruns of the X-Files (that one with the inbred farmers and the hillbilly mother on a skateboard under the bed—oh my god) without pacing the floor or peeling fruit with frantic intensity. And the thing is, we’ve all been there—caught in a moment listening to someone describe a movie we know we’ll never see, a movie we might like to stop talking about because it bores or aggravates or even unsettles us, distracting us from the thing we’d prefer to discuss. Except here is where things get tricky, because this wasn’t that moment at all. This was an altogether different experience because Bruce Lack happens to be an excellent storyteller, one capable of deftly managing pace while still finding room to weigh in on the psychological nuances of the tale. So compellingly did he deliver the play-by-play of this horror flick about murderous mole people that I found myself leaning in, wondering with no self-censure whatsoever, But what did Sarah do after attacking Juno with the pick-axe? What’s stronger, a crawler’s sense of hearing or his sense of smell? When Bruce Lack tells you a thing, you care about it. This is not only because he puts words in the right order but because of a rarer, more vital artistic quality: a sharp instinct into the stakes of human survival, the tiny spinning center of all good stories.

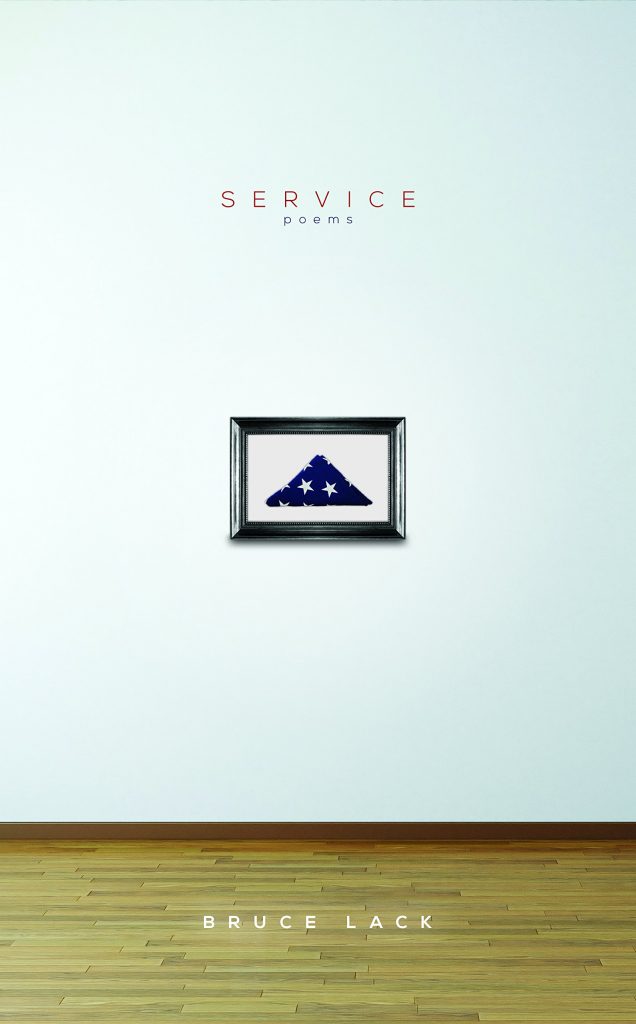

Service, Bruce Lack’s debut poetry collection, centers around his experiences as a Marine in Iraq—the deployment, the hardships of battle, the frustrations of returning home. “There is no funny business in Service,” writes Diane Seuss, “no fragmented text, no baloney a Marine would distrust. The voice in these poems is that of a man for whom all artifice has been blown away. The searing poems of Service are heroic in the artfulness and generosity of their telling. There are boots to the sand and then there is the language of boots to the sand, the holy language of witness.”

To read Service is to learn the rules of engagement, and later, the methods of disengagement, if there can be such a thing. We slip backward and forward in time, one unwitting, vulnerable foot perpetually in enemy territory, one moment searching under the couch for a hair tie and the next moment, “in a hallway I will never be able to describe, I gulp crematorium-hot air and drip sweat onto the flak-jacketed back of my best friend, who will breach the door and survive the next several seconds. When I knee him he moves as if lives depend on it. Lives depend on it.” We feel whisper-close to the action and at the same time impossibly, embarrassingly removed: “Jesus Christ, get up / off the deck, hard-charger, / incoming happens all the time. / If you heard it, it didn’t hit you”—such are the speaker’s directions in “The War According to Master Sergeant Marsh,” a poem that leaves us blushing, brushing desert from our knees, and hardening our hearts. We’re soldiers, too, tramping through the heat and dread, and then “Thirteen Months of Talking to God” comes along to remind us how much we cannot understand: “Lord help / me help us all / Christ Almighty Jesus / let him / stick his head / up / again oh / Jesus— / if you’re there, / look away.”

Winner of the Walt-McDonald First-Book Series in Poetry, Service (Texas Tech University Press, 2015) is a compelling, unputdownable collection. I had the pleasure of interviewing Bruce on topics ranging from war writing, to craft, to poetry as an act of empathy.

Let’s start with something basic. When did you start writing?

I’ve always known I wanted to be a writer–which is not remotely the same thing as actually writing, of course. When I was younger, I didn’t think I had much to write about, or the skill to make growing up poor seem interesting. It wasn’t interesting to me. Just frustrating. The socioeconomic gap at my school was pretty pronounced, so I didn’t really feel I had the luxury to try being a writer and have it be okay to fail. Starving artists are a romantic notion unless they are, you know, actually starving.

Did you always take the writing serious?

I mostly dreamed about writing without doing it in earnest until after I got out of the Marines. Getting out of the Marines is like dying: you do it alone. I was disconnected from the built-in support of my platoon, disoriented from having been actively at war just two weeks previous, and suddenly surrounded by civilians who didn’t even think of themselves as living in a country at war. I had to do something to quell the urge to shake the hell out of people and yell, “DO YOU KNOW WHERE I’VE BEEN?” Can’t do that or you’re just another vet who lost his shit. So I started seriously writing instead.

The most basic way to summarize Service is to describe it as a collection of war poems, a response to your time as a Marine in Iraq. Do you feel that’s an accurate description? Would you complicate that summary?

I think that description is accurate-ish. I think Service is also about coming home, trying to re-assimilate into a culture that 1) seems to have changed radically in the time you’ve been away, 2) is somewhat distasteful in its refusal of complicity in your experiences, and 3) thinks that Support the Troops bumper stickers and the ever-maddening “Thank you for your service” counts as “doing their part.” Total war, this ain’t.

What drives you as a writer?

As a writer, I just hope that my work becomes part of a greater dialogue that we need to be having in this country, where the realities of war are so far removed from the lives of the citizenry. I read an article the other day about embracing war with Iran as the strategy of choice. Written by a man who had no danger of having to actually fight the war he so cavalierly proposed–who had, in fact, actively avoided service in the war he was young enough to fight. At one point, he spoke of the acceptable reality of American forces having to “absorb some hits.” As if we’re talking about a boxing match, all neat rules and padded gloves and absorbing hits. I remember thinking, “this asshole has never seen how a humvee ‘absorbs’ the explosion of an IED.” I hope that people will read Service and have a thought for the actual cost of war where the rubber meets the road. It’s hard to describe without sounding preachy. On a practical, much more achievable note, I hope my work can help my fellow veterans.

Because much of your work is drawn from lived experience, what is the writing process like for you in terms of calling up memories you might otherwise wish to leave alone?

Generally those memories are coming either way. With the writing, I can turn them a little. Does that make sense? Like using a much bigger opponent’s momentum to throw them. It’s still a question of self-defense. I don’t have much of a captial-p Process, per se. Something sets me off, and I write. Though I do prefer to be alone in the house when I write because getting back into that headspace means inhabiting and redirecting a lot of anger.

In “Conversations We Might Have, If We Could,” we learn the worst question to ask a veteran; I’m curious to know what you think is the worst question to ask a poet.

“How’s that going for you?” I think all writers have heard this question, usually in the same tone of voice folks use when talking to children, the cognitively impaired, or other subsets of the population they feel better than. I hate that question; and the fact that, for non-artists, success–and therefore satisfaction–can only be expressed in terms of the quantifiable. It’d be much more honest if they’d just ask how much money I’m making from it.

Rumi wrote that poetry “can be dangerous, especially beautiful poetry, because it gives the illusion of having had the experience without actually going through it.” How do you think such an observation figures within the context of poetry about war?

I don’t actually think I agree with Rumi on that. Poetry gives the reader a chance at a profound act of empathy, which at its best inspires readers to go out and have their own experiences. I don’t imagine people will read my book and have the illusion of actual warfighting experience. Just an echo of it, and hopefully a much better understanding of what they don’t know or didn’t consider about war. But I do think that readers who have experienced trauma of any kind will experience a resonance with my work. I think the beauty of poetry is that readers connect in their own way and take what they need from your work. Reading Robert Frost’s “Birches” for the first time as a child, I was struck not with a proxy experience of swinging on birch trees, but by a vivid memory of the trees in my neighborhood bent over from an ice storm. An impression of silence and beauty in my own world from Frost’s description of his.

Then again, if Rumi is right then surely the best way to experience war is through poetry about it rather than the actuality of combat. I’d highly recommend the former.

Do you agree with Neruda’s assertion that “poetry is an act of peace”?

I love Pablo Neruda. I’d agree with him in a knee-jerk way just as a groupie. Then I’d try to find a way to make my deviations of opinion sound like agreement so he’d still hang out with me. It’s true that I derive some peace in my life through writing poetry, but I’d be lying if I said it didn’t also cause frustration, anxiety over being misunderstood, hope, communication. That’s mostly it for me: my poetry is an attempt to communicate with civilians.

On a craft note, some of the poems in Service, such as “When Reid Died” and “David Gomez: El Paso, Texas,” have very short line breaks, whereas poems like “As Long As I’m Wishing” and “That Feeling You Can Only Describe in Arabic” have no line breaks at all. Can you speak to how you decide where and whether to break a line?

With “When Reid Died” and “David Gomez” I was hoping to convey the necessity of cramming something huge into a compartment too small to contain it. “Reid” is kind of a sucker punch poem. I hope the short lines disorient and stun. And short lines and short poems encourage the reader to spend more time with them, read more than once, read in different tones and paces. The block texts like “As Long As I’m Wishing” and “Arabic” are meant to be heavy. There are also practical concerns: “Wishing” is a one-sided, literal speech act to a mute religious figure and “Arabic” is a cascading stream of connections made in a split-second of real time. Both are about mental processing, and in the same way that these experiences hit your mind all at once and then have to be gradually parsed, I wanted readers to be confronted with blocks of text.

What sort of changes happen during the revision process for your poems? How did you decide which pieces were right for the book?

Revision is mostly learning an effective way to be suspicious of your first instincts as a writer. What comes out first is rarely the final product, because the language of the heart and mind is completely different from the language we speak. Something is lost in translation, and revision is an attempt to get some of it back. Sometimes it’s curbing your atavistic desire to reduce everything to pieces, sometimes it’s reigning in your tendency to make artistic flourishes. Always it’s admitting that you aren’t quite as brilliant as you wish you were.

Sequencing a book of poetry is its own kind of hell. You spread your poems out on the floor, and stand on a chair overlooking the concrete product of months or years of work. You arrange the poems chronologically by when you wrote them. That’s stupid. You arrange them chronologically by experience. That’s too storybook-y and besides a few of them are unmoored by time completely. You arrange them alphabetically by title. That is the stupidest sequence yet, but its ridiculousness frees you: having perpetrated that incoherency, you are now capable of anything. You arrange the poems by how you feel they convey themes/transformations in your life. This sequence is most subjective, least clear to anyone besides you, the poet, and just feels like the best. You still aren’t satisfied, but you feel you’ve done your best and you’re ready to stop crawling around on the floor. You realize that you’re still holding poems in your hand. Some of your personal favorites. You get a little frantic trying to make them fit somewhere but they don’t. You promise them space in your next book, and hope you aren’t lying.

You’ve become a father since composing many of the poems included in Service. Has parenthood changed either how you write or how you see yourself as an artist?

Parenthood has changed the time I get to dedicate to being an artist, and at the same time raised the stakes of making this endeavor count. Time spent writing has to be more effective now because it’s time I could otherwise have spent cooking or cleaning or at either of my non-artistic jobs. There’s a mathematical equation of fatherhood that has to come out positive before I can start being an artist. My adorable little tyrant doesn’t care how close daddy was to stitching together the vignettes he’s been writing into a coherent whole during naptime: he’s just awake and wants a diaper change, food, and to read “Bats at the Beach” seventeen times in a row. I’m learning to carve out time and try to work more in tightly focused bursts, but it’s definitely a process.

Can you talk about what you’re working on now?

I’m writing poems always, of course. Still war poems. Another annoying question for war poets is “when are you going to write about something else?” How is that not offensive? It sounds an awful lot like “when are you going to abandon your schtick and write REAL poetry?”

I’m also writing nonfiction that I think is serving me very well at the moment. I feel connected to it, and it allows me to get at more of what my poems approach peacemeal. I’d call them lyric essays, though that may be a little too highbrow of a descriptor. The hardest part is getting them to hang together in a way that makes them an aesthetically pleasing whole.

Let’s switch gears; I want to present you with a scenario: you’re Kevin Costner’s character in Waterworld and you have room for five books on your makeshift shanty boat. What do you keep?

If I had to be dystopian Costner, I wish I could have been the Postman. These questions are hard: you always want to sound smart without being dishonest. Like “what would the best version of me take?” Or show off my cleverness by going with five nautical themed classics or cheating by going with five anthologies. Well, I’m going for honesty here: what the version of me who has to live life on a shitty boat, water-hating and sunburning every day, would take. Personal favorites, and pure escapism:

The Old Man in the Sea, by Ernest Hemingway, so I can feel like someone in a boat has it worse than I do.

To Kill a Mockingbird, by Harper Lee.

World War Z, by Max Brooks.

It, by Stephen King — roll your eyes all you want, intelligencia. In Waterworld, your rafts probably capsized from all the Tolstoy and Shakespeare.

The Poetry of Robert Frost: the Collected Poems.

There. I’ve revealed myself to be sappy and pulp-loving. But if I have to endure hellish boat-life, I could do it with those five books.

What books are top-of-list for you to read in the near future?

As a veteran who writes, people always expect me to know every other veteran writer’s work, so I should get on that.

Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, by Ben Fountain.

Redeployment, by Phil Klay.

Refresh, Refresh, by Benjamin Percy.

All kinds of poetry:

Claudia Rankine’s Citizen.

Laura Kasischke’s The Infinitesimals.

Gary McDowell’s Weeping at a Stranger’s Funeral.

The list goes on, and I’m reading at a glacial pace these days between dadding and working and writing. But I’ll keep chipping away.

To wrap up, are you game for an irreverent round of Literary Would-You-Rather?

Absolutely I am.

All right, here goes. Would you rather be devoured by a man-eating lion or cowboy poet Wally McRae?

The lion. He’s a pro and would finish me quickly.

Would you rather spend the rest of your natural born days writing dirty limericks or dirty haikus?

My ancestry is Irish, so I was born for dirty limericks but there are already so many. Dirty haikus for their novelty.

Would you rather be trapped on a deserted island with Lord Byron or William Blake?

Lord Byron. He was well-traveled, adventurous, a scrapper. I feel he’d be better in a survival situation than Blake, who spent almost all his life in London.

Would you rather serve as the personal poet laureate to Justin Bieber or write the crossover screenplay for Saw VIII: Sisterhood of the Traveling Husqvarna?

I’m ALREADY writing the crossover screenplay for Saw VIII: Electric Boogaloo.

Would you rather act as a waiter at Bread Loaf or as Henry VIII’s Groom of the Stool?

I hear Henry’s grooms of the stool had quite a bit of clout. And at least they make no bones about having to suffer shit to make their break.

Would you rather be abducted by extraterrestrials with no capacity for understanding poetry or be forced to travel the galaxy with poet-aliens who endlessly argue craft points?

No understanding of poetry is probably better than an endless back-and-forth nit-picking of craft points. Again, I respect the honesty of the aliens that say “we don’t get it. And we never will.” Plus I would be sure to be the most talented poet on the ship.

Service is available for purchase through Amazon.com and Texas Tech University Press. For more information on Bruce Lack’s current and upcoming projects, follow him on Twitter at www.twitter.com/TheBruceLack.