“I think the subject matter is there more than anything else,” Philip Levine told David Remnick in a 1980 interview in Michigan Quarterly Review. Remnick—at that time an undergraduate at Princeton—had asked Levine about the lasting aural effects of Detroit in his work.

REMNICK: There are certain New York poets like Allen Ginsberg or Ohio poets like James Wright whose origins influence the rhythmic quality of their work. Do you think there is anything that Detroit contributed to the sound of your poetry?

LEVINE: I think the subject matter is there more than anything else. It seems to me that the rhythms of my poetry come from the history of poetry in English and songs that I’ve listened to and the way people speak. I think if you knew Detroit and then read the poems you would say “this is the cityscape of Detroit, this is the tone of Detroit.” There is a certain kind of defensiveness and aggressiveness there; it’s a very masculine city to a disgusting degree. Everybody’s so goddamn aggressive, they are ready to punch you for nothing.

REMNICK: That aggressiveness is very evident in the early work.

LEVINE: And I think it continues in my work. It’s a healthy cynicism. We’re all being lied to and a healthy cynicism is one that says “Hey, those are lies. Don’t give me that shit, I don’t believe it.” That’s what you derive from a place like Detroit.

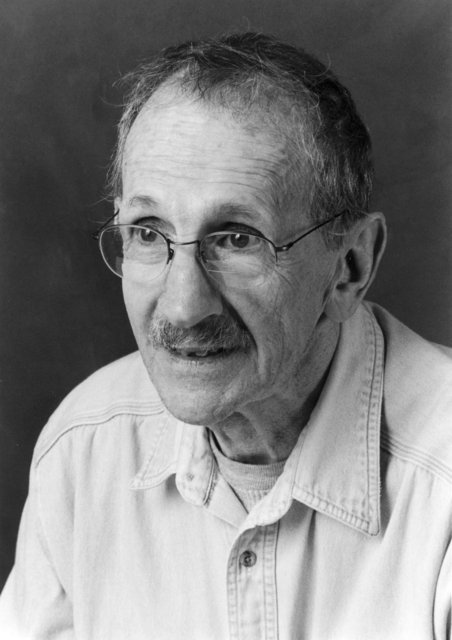

That interview, of course, was thirty-five years ago; Levine passed away on Saturday at the age of eighty-seven; and David Remnick is now a household name in magazine journalism. At the time of their interview, Levine’s poetry had already been recognized by the American Academy of Arts and Letters as well as the National Book Critics Circle; a Guggenheim fellowship and National Book Award in Poetry that year would further endorse him as an important figure in the twentieth-century canon. More accolades would follow: a Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, another National Book Award, a Wallace Stevens Award and the appointment to United States Poet Laureate.

Times, people, mastheads—they all change. What will go on is Levine’s legacy at home and abroad. In Ann Arbor, Levine has long been loved and revered through his ties to the university and local literary community. At Michigan Quarterly Review, Levine played a crucial role in developing the journal’s voice and style these last three decades. His importance to the region cannot be overemphasized. As MQR’s former Editor Laurence Goldstein wrote following Levine’s nomination to Poet Laureate in 2011:

Levine extended the range of Detroit poetry in crucial ways, […] especially by focusing on factory work, and did so plainly and forcefully, in one artful poem after another, from the 1960s to the present. What Charles Baudelaire did for Paris, and Walt Whitman for New York, Levine has done for Detroit. Every poetry reader in the state of Michigan knows his work and speaks of it with reverence.

Goldstein goes on to stress the continued—if not renewed—relevancy of Levine’s work, not merely in Detroit, but nationally:

During the last few decades the state of Michigan has needed this local voice, stoical and fervent by turns, to console and uplift during times of trouble. Now the whole country would do well to take note of his gritty and eloquent poems. It is customary for schools in all fifty states to expose students to the work of the current Poet Laureate as part of their lesson plans. Levine’s narrative poetry is capable of making contact with young and old alike.

Indeed, in light of economic downturns leading to greater divides between the privileged and working classes, Levine’s poetry only seems to increase in relevancy. Never has there been more urgency for, as Edward Hirsch noted in his essay “Naming the Lost: The Poetry of Philip Levine,” poetry that reflects “the stubborn will of the dispossessed to dig in and endure.” Such poetry is not merely ornamental—it is practical, useful even. In his 1997 Hopwood lecture delivered to students and faculty at the University of Michigan, Levine himself spoke to the need for poetry to be just that: useful, necessary, a portal to the sublime.

I confess I not only find poetry useful these days, I find it absolutely necessary. I am presently living in one of the most complex, turbulent, disturbing, unfathomable communities in the world: New York City. Even my twenty-six years in industrial Detroit failed to prepare me for this. But through the work of its poets—Whitman, Hart Crane, García Lorca, and Galway Kinnell—I have come not only to a degree of peace with all the tumult, I have also become so comprehending of its presence that at times I can see its ordinary diurnal street life as the arena of the sublime and the sacred.

And in that statement Levine delivers one of the finest, lasting pieces of advice I’ve ever read: look into the abyss and discover the sublime, not merely for the sake of poetry but for the sake of sanity and survival. Don’t let the bastards grind you down—dig in, reconcile yourself to the tumult, and endure.

Goodbye, Philip Levine. You will be deeply missed.

FROM THE ARCHIVES (SPRING 1989: VOL. 28, NO. 2): Click here to read “My Grave,” by Philip Levine.