When we encounter images of the dead, how does looking proceed? It might begin with mourning, a mourning that clouds the image the way the oils on human skin cloud glass, because we know what comes after the image. Cruelly, we can see over the subject’s shoulder and beyond the horizon. If you knew the subject, this mourning is not just for them, but for the period of innocence you once had as a viewer, when the image’s tyranny of stillness did not dominate your memory: the period where you could look from a photograph or a video to the living subject beside you, watch time unfreeze itself.

But if you have encountered a photograph of a person only on the occasion of his death or years after – as was the case with the first photos most of us saw of Eric Garner and Michael Brown this summer, and as is the case with most of the photos that introduce the victims of historic tragedy and injustice – you mourn for the fact that never in your life will you have been able to look at these photos of a man embracing his wife at a party, a boy graduating from high school, without knowing what comes next.  In the wake of their deaths and the non-indictment verdicts for the cops who killed them, small clusters of Michael Brown’s and Eric Garner’s images quickly became iconic. Brown in a cap and gown, his gaze lowered slightly, his mouth set, the hint of a goatee; Brown looking quizzically at the camera with his headphones on, an arcade in the background, his face looser. In the first, he tells the camera nothing; in the second, his eyes reach out, you can almost feel the start of a silent conversation between Brown and whoever is behind the camera – someone he surely knows.

In the wake of their deaths and the non-indictment verdicts for the cops who killed them, small clusters of Michael Brown’s and Eric Garner’s images quickly became iconic. Brown in a cap and gown, his gaze lowered slightly, his mouth set, the hint of a goatee; Brown looking quizzically at the camera with his headphones on, an arcade in the background, his face looser. In the first, he tells the camera nothing; in the second, his eyes reach out, you can almost feel the start of a silent conversation between Brown and whoever is behind the camera – someone he surely knows.

Because he was older, and perhaps because there was already a horrifying moving image of his death, a greater number and variety of still images of Eric Garner seem to have made it onto the public web. There is the image of him and his wife, Esaw, both dressed in red, faces broken into smiles; the image of him with four of his children; and one of him as a younger man, in a dress shirt and bow tie, sitting for what looks like a graduation picture. This last image has been silhouetted and silkscreened onto signs and banners like the one hung outside Spike Lee’s 40 Acres offices.

These men, dead, have been introduced to the country mostly by way of the use of their faces as symptoms of an epidemic of racially motivated police violence and symbols of a movement to protest that violence. The trickle of candid images of their lives is important, because as we memorialize them, as we amplify their faces and gestures and last words, we are enlarging the last moments of their lives, but little more. Critics have warned against memorializing Michael Brown by writing about him as college-bound or a “good kid,” because the extent to which a young black man is “good” shouldn’t be the criterion for keeping his life. They are right, but as protesters call for an equal valuing of black lives in America, it’s also essential that we look directly at those lives: not as a silkscreened or abstracted image, but as collections of human moments.

We are lucky, maybe, to live in an age of images, of constant capture: so that even in death, the ordinary weight of a life in photos pushes back. Look long enough at Garner’s smile as he holds his infant daughter, his wife’s and his grins as they embrace each other; the combination of teenage reticence and playfulness in Brown’s eyes, and it’s almost possible to enliven them, to recreate the stream of stolen moments before and after these photos were taken. We don’t really know them, and we never will. But imagining that continuity, the weight of that life, is a powerful antidote in a country whose status quo asks us to always cloud our vision when we look at black men and women; in a country where many of us may be looking more often at photos of pre-dead black people than living ones.

~

How will our treatment of the images of black victims of police violence look in fifty or seventy-five years? How will we remember remembering them? I think of the difficulty of looking at images associated with other tragedies, the challenge to see life where we have been taught to see death. In the 20th and 21st centuries, American Holocaust education has encouraged us to look at every pre-war photo of a European Jew, from Anne Frank on, with gravity and mourning. Like our images of Garner and Brown, the Jews in these photos are not alive but pre-dead. The teenage Anne Frank was by most accounts a social butterfly of a girl who was crazy about boys and a little bossy. But when an iconic school picture of her face is covered with the Dutch yellow star reading “Jude,” it’s hard to see her as anything but a Holocaust victim. There’s danger in this kind of memorial, obsessing over the details of death at the expense of countenancing the complexities of a life.

Currently on view at the Museum of the City of New York is an installation, Letters to Afar, based on nine home movies taken in the 1920’s and ’30s by Polish Jews who had emigrated to New York earlier in the century and who paid return visits to Vilna, Warsaw, and a number of small towns in the years before World War II. The prevalence of the amateur movie camera in America made it possible for these immigrants to film daily life in the country they’d emigrated from: children walking to school, young girls sitting in a field applying lipstick. Because moving images were still in their adolescence, some of their subjects did not know how to behave in front of the camera. Some stare into it, as if sitting for a photo. Trying to hold their poses, they betray subconscious tics and gestures that a still camera might never show. These movies were taken to help elicit donations from American Jewish societies who had come from the same cities and towns in the films; and they were taken as a kind of painstaking status update, to show American Jews what life was like for the people they’d left behind.

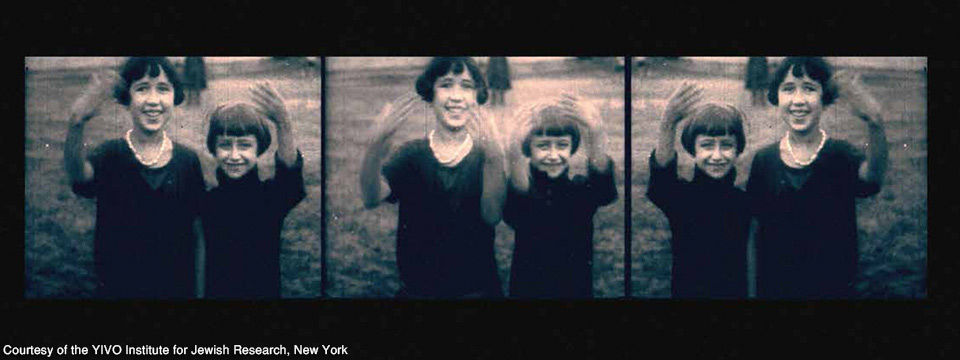

Peter Forgács, the Hungarian artist who manipulated digital transfers of the films and paired them with original music, edited and arranged them in the gallery so that they play in loops, often with the same image shown twice in one screen, in staggered time. Moments repeat, as we sometimes talk about moments doing in our memory: a woman staring into the camera rearranges a lock of her hair again and again; two young girls wave their hands at the camera (goodbye? hello?); a man walks toward the camera until a frame where the artist cuts him off.

For the viewer in mourning, these repetitions ring of preservation, of the grasping we do after great loss. In the mind of the mourner, these images repeat because they are trying to stay, clinging not only to the film or the walls of the room but to the insides of our heads. Most viewers, maybe especially Jews, see the exhibit for the first time with this gauze of mourning. The music piped through “sound showers” overhead, the silence of the sepia faces, even the little girls waving, all gets recast as an elegy.

When I first viewed these films, I mourned, too – but I found it hard to linger there, because I was surrounded with the repetitive evidence of life, people taking out the trash and serving food, reading and lounging and walking. These bodies moved, they carried out their last (and in many cases, first) recorded motions. Peter’s carefully timed repetitions turned thoughtless motions into a kind of dance. The woman’s hand moving up and over the crown of her head became part of this dance vocabulary, as did a strong arm hefting a bag of trash, and the little girls’ odd wave that could signal beginning or end. By my third viewing, the gestural vocabulary highlighted by Peter’s repetition was thrown into relief. As with a stage-lit image of a real dancer, the high contrast of the black and white film exposed to natural light was dramatic, accentuating the urge of the eye to follow the body. I felt a transformation in the way I viewed these people: I wanted to mirror their gestures, to speak to them and hear them speak back to me.

Photography and film can serve as evidence of life, and yet it can take forever to really see life in a photograph. Because of the Internet, the photos of unjustly lost lives come at us faster now than the photos or films that predate or document earlier tragedies. And thanks to the ease of capture, there are more ordinary photos of the black men and women who have been killed in recent years than there are of earlier victims. Let this technology teach us: we owe it to the wrongfully dead to put their images together, to make them move, to talk to them even as we try to amplify their voices. We can never un-know what we know, but we can know more than that.