This is the second in a short series of posts on directors’ first films—films often overshadowed by the blockbusters that come after them but that catch their makers at an important stage of evolution while providing plenty delights of their own.

* * *

Some directors are known for the distinctive styles and sensibilities they return to with each project—we might think of Wes Anderson’s films, for example, as each participating in some way in a single world, or cinematic worldview. Other directors reinvent themselves again and again, protean and unpredictable. A different Anderson—Paul Thomas—is such a filmmaker. Each of his offerings shifts the direction of his trajectory as an auteur, and this flexibility is for me often as pleasurable as the more expected and reliable output of directors I wholeheartedly love. In fact it makes more sense I think to speak of P.T. Anderson’s worlds, in the plural—a variety not only of specific places and times but also of narrative, formal, and stylistic choices and strategies.

What are these worlds? In his most recent film, The Master (2012), Anderson introduces us to “The Cause,” a post-WWII touring cult group. The broody There Will Be Blood (2007) takes us back to the early days of the oil boom in Southern California, while Punch-Drunk Love (2002), a romantic comedy, represents something of an aesthetic departure with its tight and linear (if puzzling) portrait of a troubled consciousness—a kind of world itself. To move back further still, Magnolia (1999)—braiding the worlds of TV quiz shows, police investigations, and self-help dating courses—expands upon the large-cast polyphony attempted earlier in Boogie Nights (1997), an excursion into the “exotic film” industry on the brink of the 1980s.

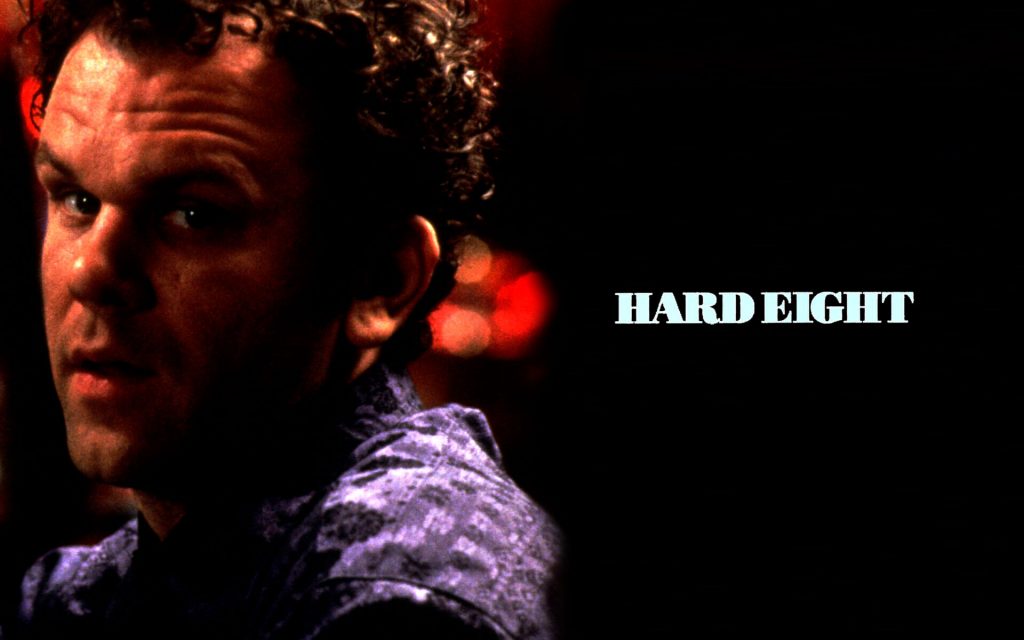

Which brings us to P.T. Anderson’s modest but mature feature debut, Hard Eight (1996). Like many other first films, this one began as a short, or rather as one strand of a short, called Cigarettes and Coffee (1993). It’s a cigarette or a cup of coffee that Sydney (frequent collaborator Philip Baker Hall) offers John (John C. Reilly, another actor Anderson has often called on) in the opening scene of Hard Eight. From there Anderson begins his world-building quickly, as Syd goes on to give John—who’s been in Las Vegas trying without luck to win the $6,000 he needs to pay for his mother’s funeral—a chance to get back on his feet. We enter Syd’s world of casinos and gambling alongside John, who takes every order he’s given, from shaving in the men’s room to scamming the casino into comping him a free hotel room and two tickets to a show. Syd delivers his instructions with the cool certainty of a mentor; John follows them like a disciple. The former’s in the know, and the latter knows nothing. And as it turns out, knowledge is a valuable currency in the world of this film.

Knowledge and its close cousins power and trust—the three in some ways exchangeable (not to say interchangeable) with each other. When we first meet our two protagonists, John is the powerless, vulnerable one, positioned defensively on the ground outside a truck stop diner with his knees drawn to his chest, his head lowered resolutely. Syd approaches John with his back to us, imposing, his body too big for the frame. It doesn’t take very long for him to win John’s trust, though at first John resists. Syd promises John that he can help him stretch $50—which Syd will provide—farther than he might imagine. “You think you’re St. Francis or something?” John asks. “I’m offering you a ride,” Syd responds. “I’m offering to teach you something.” Just about sold, John adds, as a warning: “I know three kinds of karate: jujitsu, aikido, and regular karate.” (This is John C. Reilly, remember.) “If you try to fuck with me, I’ll fuck you up.”

On the drive to the casino, we see Syd’s $50 bet on John begin to pay off. “This is a nice ride, actually,” John says from the car’s backseat, where he’s demanded he sit. “Comfortable. Can you pull over for a second?” Cut, and John’s in the front passenger seat now. In another beat he’s holding the wheel, both their lives literally in his hands, while Syd lights a cigarette—and revealing his bad experience with a book of matches. (They suddenly burst into flames in his pocket. Yes, perfectly, there’s a flashback. “Spontaneous friction, I guess.”) By the time they get to the casino, he’s ready to learn.

And seeing John learn how to scam the casino is one of the highlights of our introduction to this world. In the scheme, John asks the casino’s floor man for a rate card, which will record the amount of money he spends in a night. By repeatedly exchanging cash for tokens at one counter, where he has the rate card marked, and exchanging tokens for cash at another counter, where he doesn’t, it looks on paper like he’s spent much more money than he actually has. And the more money he spends, or appears to spend, the more generously the casino will give him complementary gifts—the hotel room, the show tickets. In other words, cheating or not, he’s buying the casino’s trust.

After a two-year jump, we meet Clementine (Gwyneth Paltrow), a waitress/prostitute at a Reno casino restaurant. Syd takes her in just as he did John, with some kind words and an extra-big tip. At the same time, Syd himself refuses to be bought by Jimmy (Samuel L. Jackson), a casino security guard who pays for Syd’s drink from across the room. These two threads—Syd’s surrogate parenting of Clementine and John, and his power-struggle with Jimmy—wind together as the film heads toward its climax. After John beats a man unconscious for not paying Clementine, Syd sends them to Niagara Falls for a honeymoon of sorts (they’ve just impulsively married that afternoon) and to lie low. With them out of the way, Jimmy arranges a meeting with Syd where he plays the film’s last card (SPOILER ALERT). “I know you,” he tells Syd—what he knows is that back in Atlantic City sometime in the past, Syd killed John’s father. Now he tries to wield this knowledge over Syd, demanding $10,000 at gunpoint if Syd doesn’t want him to tell John. A true high-stakes gambler, Syd says he only has $6,000. It works, and Jimmy takes the money to a casino, where he wins big on the hard eight—double fours on the craps table. But when he returns home with a woman he’s picked up at the casino, Syd is there waiting for him.

As a rule, I cannot abide withholding in movies. What if we knew the whole time what we learn about Syd at the very end? What if John were to find out? How I’d love to see what he’d do! But that would be a different film. And the decision to delay the revelation may be early proof of P.T. Anderson’s genius as a filmmaker: he commits so fully to the world of gambling that its rules—withholding, bluffing, persona—become Hard Eight’s rules, too, shaping what the film has to say about power and trust. Did we really think Syd had no ulterior motive? Were we misdirected by the fact that Syd is estranged from his own children? Were we taken in by his straight face? I was. It’s the rate card scam all over again—by saying less than he knows, Syd gets out more than he puts in. But then in the film’s final moments he calls John on the phone: “There’s something I need to tell you,” he says. “I need to tell you I love you. I love you like you were my own son.” After a speechless moment, John replies, beginning to cry: “Thank you, Syd. I love you, too.” I didn’t feel cheated.