In my Facebook newsfeed last week, a poet’s status alerted me to the fact that Beyoncé’s self-titled album dropped on iTunes. Its unconventional (unpromoted, unannounced) release caused a bit of stir, as did the nature of the songs. I’m not someone hip to what’s happening in music right now, and certain popular bands or artists usually only trickle into my awareness by way of friends whose tastes I trust. After my late twenties, consumption of popular culture has been strictly on a need-to-know basis, which usually means whatever celebrity- or artist-I’ve-not-heard-of is being referenced by a writer I like, and requires my googling them. Often, the contrarian in me resists anything too many people like. For these and other more banal reasons, my purchasing the album that Saturday morning was unusual. But I bought it, and listened, and watched the video album.

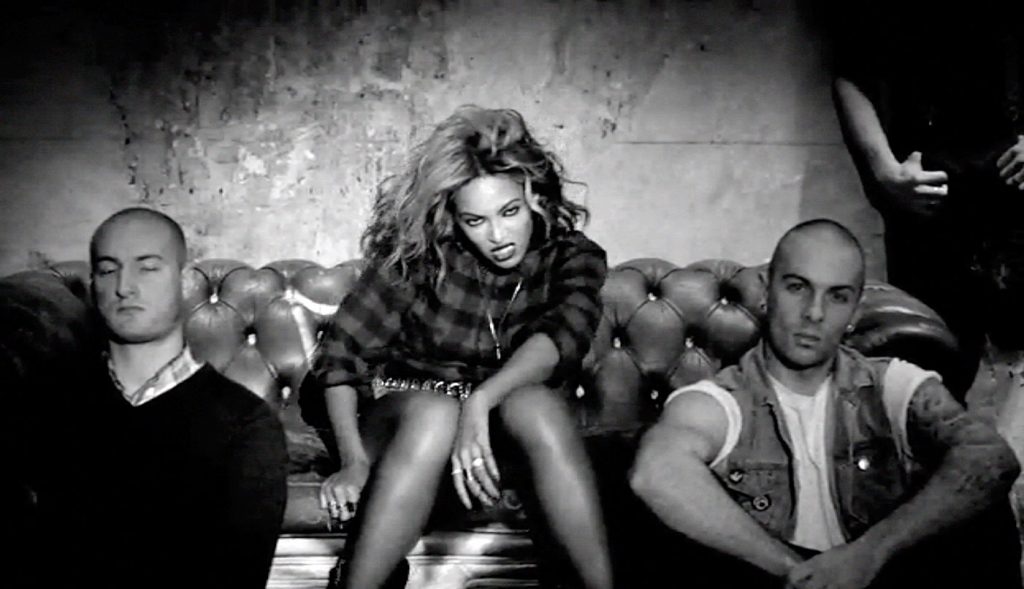

Three videos in, I developed what can only be described as a massive girl-crush on Beyoncé, the likes of which recalled the same kind of bedazzlement I experienced as a teen, when I was still an avid and un-questioning consumer. For all one’s acquired critical tendencies, there are some products of popular culture that either calibrate or entirely bypass those mental gears, and plug directly into the brain’s pleasure center; for a spell of time the senses are held in thrall. In the case of Beyoncé’s new album, it was a combination of sex, swagger, and vulnerability being presented to me in an operatic sequence of images, words, and music. Deeply saturated, grandiose, and with a polish and sleekness that felt more like control than a contrivance.

But maybe I fool myself to think there’s a difference? To clarify: I never once felt like I was watching a video in which Beyoncé was merely placed, or that she was but one of many elements that made up the song or the scene. Even in the more over-the-top visual feasts that were the songs “Haunted”, or “Blow”, the video seemed only to be what was happening around Beyoncé. The distinction hinges on a subjective sense of what or who I percieve to be running the production, and in my mind there was no question this project belonged to Queen Bey.

It was with admiration and pleasure that I devoured songs like “Drunk in Love”, and “Partition”, and all this was what I was buzzing on when I started reading articles about the album. The song “***Flawless”, in particular, was singled out in several of those I read, namely for its sampling of a Ted Talk by Nigerian author and feminist, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. The narrative being played out in these critical responses was whether or not this album, or Beyoncé herself, is feminist.

I want to pause here for a moment and say that listening to the song “***Flawless” had the same effect on me as listening to PJ Harvey’s 50 Foot Queenie for the first time. By virtue of what is being sung and how, listening to either song makes me feel as though I am both larger than life and perfectly inhabiting the skin I’m in. Though very different songs, they share the same core. Both elicit the blood rush of a power that feels equal parts control and chaos—the seethe of wanting to fuck shit up, and the serenity of knowing you can. There are a few songs that achieve that effect for me, but regardless the source, and cognizant of its problematic implications, I believe that was a valuable feeling for me to discover then, and for me to recall and recover now.

So, when I encountered this article, claiming that the feminism being espoused in the album Beyoncé, was complicit with patriarchy, and that the autonomy asserted therein ultimately false and destructive, it felt personal. Was I confusing pleasure with power? Does my enjoyment of this album, and my admiration for the artist, mean that I had been duped by savvy marketing? And so, am I perpetuating misogynist power structures, and betraying my feminist beliefs and ideals?

It’s not enough to say that it’s just entertainment. When someone says of anything being engaged in a critical way, that it’s just this, or just that, it sounds very much like being told to just shut up and enjoy it. And while part of me, protective of my aesthetic experience, wants to respond precisely in that way (shut up! let me enjoy it!), I could not in good faith just wave my hand or shrug my shoulders.

Especially after passages like this:

When elements of the feminist community rise up to applaud your simplistic, pro-capitalist, structurally violent sampling of feminism, the metaphor becomes even more relevant. Moreover, we’re concerned that the capitalist ethics of mainstream hip hop has seduced feminist allies into flirting with bottom bitch feminism in their silencing of those who would critique Bey and the systemic violence she represents.

Reading Real Colored Girls‘ article, and checking my emotional response to it, compelled me to recognize a few things I was taking for granted. There was a time in my life when I denied I was a feminist. It makes me cringe even to write that, but I think it’s a useful embarrassment. From friends who’ve once shared in this discomfort, I solicited reasons why, and their various responses constellated around doubts and apprehensions of what the word “feminist”, in essence, means.

My own reticence to call myself a feminist was because I felt wholly unschooled in the work and history of feminism. I hadn’t read the canon. I had an unsophisticated, and therefore inadequate, understanding of the arguments of its pioneers. I thought that to be able to call myself a feminist was something I needed to earn. The discomfort did not come from a fear of being less desirable to men (though that fear was present in other insidious and diminishing ways), but from a fear of being seen as an intellectual imposter. Feminism, as I understood it, was a kind of degree for which I hadn’t done the work.

To some extent, I still feel that way, or at least I feel that educating oneself is essential to the cause. I’m sympathetic to Real Colored Girls declaring their sense of indebtedness to our feminist forebears, and appreciate the spirit—of discourse and investigation—in which the article was written. Still, without yet having read The Feminine Mystique or The Second Sex in full, I’ve long since obliterated any hesitation I once had asserting I’m a feminist, along with the urge to modify or qualify that assertion. My ownership of that word came when I understood that feminism, more than a cache of knowledge, is a set of convictions and beliefs about social justice which guides my thinking, and living. For me, feminism, like poetry, has fashioned a certain mindfulness.

It’s after reflecting on that place of insecurity that I read the following passage with a measure of ambivalence, even as I feel a similar indignation:

Our deep and abiding love and respect for the ancestors will never permit an image of feminism wrapped in the gold chains of hip hop machismo. We ain’t throwin’ no (blood) diamonds in the air for ‘da roc, no matter how many feminists you sample over a dope beat. We’re smarter than that. We’re worth more than that.

It’s a powerful call to arms—the entire article is excellent and incendiary rhetoric—and yet I am wary of any plea for discourse that also emboldens itself, with “love and respect for the ancestors”, to regulate images purporting to be feminist. But then again, it may just be that word “permit” I take issue with.

A digression: though I distrust the intellectual appropriation and simplification necessary in any kind of ‘campaign’, the impulse driving UK’s The Fawcett Society’s ‘this is what a feminist looks like’ t-shirt campaign, addresses issues of inclusivity and misconceptions surrounding feminism with a directness and pragmatism that does not take for granted those who may still be discovering what that word means in their lives.

I think the trending hashtag, #BeyonceThinkPiece, calls attention to, but can also too easily dismiss and simplify, the dialogue her album has provoked. Regardless the intention behind the inclusion of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie words in the song, “****Flawless”, or Beyoncé’s own hedging around calling herself a feminist, the album stands as one subjective account of a feminine experience that also has things to say about beauty standards, financial independence, sex, love, autonomy, and many other feminist concerns. Though the album is still enjoyable and a source of pleasure for me, that pleasure is complicated, and what complicates an experience also deepens it. For anyone who’s ever felt like the word feminist was an epithet, or an extreme word; or for anyone who may have believed that feminism is an ideology, or a privelege, or a marketing strategy, these ‘think pieces’ serve to reminds us that a dailogue is just one of many things required in achieving feminism’s goals. So long as the questions keep being asked, we’re on track.