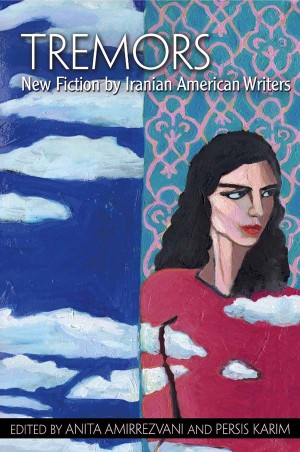

Persis Karim is a pioneer in the field of Iranian American writing. With Mohammad Mehdi Khorrami in 1999, she co-edited A World Between: Poems, Short Stories, and Essays by Iranian Americans, which was the first anthology dedicated to Iranian American writing. The book provided a home for the voices of the first and second generation Iranian Americans who had experienced estrangement, loss, and exile in the aftermath of the 1979 revolution and the Iran-Iraq War. More recently this year (2013), Persis with Anita Amirrezvani co-edited Tremors: New Fiction by Iranian American Writers, which is the first anthology dedicated to the Iranian American fiction. This landmark book celebrates the advances of Iranian American literature, especially in the past decade. Here, I follow up with Persis and expand on an interview World Literature Today had with the editors in March 2013.

You can read more about Iranian American Diaspora literature in MELUS (Vol. 33, No. 2, 2008), Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East (Vol. 31, No. 2, 2011), and Iranian Studies (Vol. 46, No. 1, 2013).

Do you see Tremors as helping usher in a new Iranian American fiction, or do you think that the literature has already emerged and the anthology reflects an existing body of works? Or putting it differently, were you looking for already published and celebrated works or for new pieces and works in progress?

Tremors is a gathering net, pulling together published writers, as well as emerging writers. I see it as extremely helpful to bring diverse perspectives, narratives and styles together to suggest there is no singular Iranian American writing or homogenous experience, but instead to offer to readers a “strong brew” of writing that can begin to focus on the idea that there is so much more than the tired and recycled headlines of the last three and a half decades. We need stories like we need oxygen. There is so much oxygen in Tremors.

Writers and critics talk about unique voice of Southern writers or Latin American writers. Iranian fiction also has specific details and textures that are unique to the Iranian culture. Do you think there is also a distinct style or voice to Iranian American fiction? If true, could you describe its characteristics?

I hesitate to equate Iranian American writers with Latin American writers. For one thing, the body of work you’re pointing to is largely written in Spanish and represents some historically and geographically specific experiences that are rooted in the history of Latin/South America over the last century. Language carries so much with it, and I believe that Iranian American writers are navigating a new language–not just the English language, but one of loss, disorientation, and responding to and against tradition as well as simply documenting and representing the experience of migrating in periods of great national crisis for both Iran and the US. Iranian culture, whether it is articulated in the first-generation immigrant writers, or the second-generation American born ones, is laced with the stories, the idioms, and the cultural memory of that larger language. It’s difficult to explain, but I sense it in many of these writers and in many of the stories. People want to belong. Language helps us find that belonging perhaps more than we can actually find it in our everyday lives. So the “characteristics” are not general, maybe even not so tangible. I think they live in the nuances, the phrases, the uncomfortable fictional characters who inhabit those in-between spaces, maybe the characters who name the uncomfortable truths of the last century or more. They are also tinged with a deep respect for the culture, and at times, with a deep sadness for what has been lost.

Is Iranian American literature different from other ethnic American literature, such as Arab American literature, with which it has much in common? If so, could you describe the differences?

Iranian American literature is not monolithic and it’s certainly not yet canonical. It’s still being shaped by the stories of arrival and the ripples of history. So, I think I resist the idea that it has a definite set of distinct features, and yet, there are definite moods I’ve observed in the formation of what I’ve seen so far in Iranian American literature. It shares many things with other American literatures. It has those contours of arrival, alienation, adjustment, defensiveness, pride, and resistance that many other literatures of US ethnic groups have. As a teacher of American ethnic literature, I think that Iranian American literature has more distinctive historical markers than some others. Because Iranians arrived so recently, key historical moments drive some of their narratives. Unlike Chicano literature, for example, which has its beginnings in the Spanish conquest of Mexico, and thus the evolution of it is tied to a much longer period, Iranians really begin writing when they arrived here in larger numbers in the mid-twentieth century. Their narrative arc as Americans, has a great deal to do with the events of US involvement in Iran, with the Cold War, with the CIA-backed military coup and overthrow of Mohammad Mossadegh in 1953 and, later, with the Iranian revolution. Those certainly are not the only events, but they’re important ones in the timeline of 20th century Iranian history. Certainly, the arrival of Iranians as university students to the United States in the 1960s gave narrative context for Iranian American literature as well. I think, though, Iranian American writing has that distinctive sense of dissonance that can be seen in Arab American literature and is caused by many things, not the least of which is a culture that is Eastern, Muslim (even if there are a number of religious and ethnic minorities in those societies) and bound up in a larger story of “difference” that has dominated the West’s view of the Orient generally. It’s hard not to see the psychological texture of that difference in Iranian American writing, and of course, that difference was magnified after the events of 9/11.

In her review of the anthology, Manijeh Nasrabadi questions whether “the writer’s job [is] to challenge stereotypes about Iran and Iranians, to educate American readers about Iran as an act of literary diplomacy.” Do you believe Iranian American writers are challenging these expectations? How do they write against type and what is expected? How do they problematize the notion of identity and the essentialist views of Iran and America? Does the art of fiction versus non-fiction or poetry help them achieve this goal in a special way?

I don’t necessarily think it is the job or responsibility of any writer to right a misperception or a stereotype generated by others, but I understand the impulse for some writers to want to humanize and complicate such representations. I think some of the Iranian American writers in Tremors and elsewhere are interested in the complex characters that can only emerge from such a complicated nation and a history of a place that is both rich and troubling. I think a good writer is more interested in the human, rather than the specific national or cultural story, but naturally they are drawn to what they know, or what they want to know better, and thus that interest finds it way onto the page, sometimes consciously and sometimes unconsciously. But really good writing almost always cannot fit comfortably inside a neat box (of stereotypes), and by its nature it problematizes. For Iranians and Americans who seem to be endlessly locked in a dance of misperceptions (at least at a governmental and political level), the really interesting stuff is beyond the essential. I’m very impressed with how many of these fiction writers write so well about this. I think each genre–poetry, fiction, nonfiction–has contributed cumulatively to a less essentialized view of Iranians and Iranian identity, and I think at this moment, I’m finding fiction has more allure for me and for many others; perhaps because fiction does, by nature, liberate us from any need for “essential” truths. And, perhaps too because there are just so many interesting stories still yet to be told.

It is noted that American readers and publishers look for and promote Iranian or Iranian American women writers writing about oppressed Iranian women. Critics have pointed out how this can be seen as part of the problematic western mission of unveiling and freeing Iranian women, as well as condemning and modernizing (or democratizing) a backward misogynist nation.

I think there are two issues here: the missing Iranian American male writers and the narrative with a specific female protagonist. I know you have been aware of these issues. Unlike your last anthology, Let Me Tell You Where I’ve Been, which focused only on Iranian American women writers, Tremors has one-quarter male authors. A number of stories in this new anthology also have male protagonists. Can you talk more about these issues? For example, are there just not enough Iranian American male writers or are their works not as good? Are the Iranian American males and females hailed differently by the American media and its readers?

This is a difficult question for me to answer. I can speculate all kinds of reasons why women are more widely represented (so far) in all the work of Iranian American writing I’ve read and been involved with as an editor, but it might be speculation. I suspect the reason is a confluence of factors and events, but I think the writing is still evolving, and that we don’t know what this literature will look like in ten years. This is a still a young literature, really. Iranian American writing seems to have gotten the attention of American, British and French publishers after the Iranian revolution, through the lens of how Iran was viewed most distinctly as anathema to those societies–through the Islamicization of a country that was formerly friendly, even embracing of American/Western culture, and probably most immediately in the idea of how women were influenced by western values and culture. This subject became the first window onto Iran and Iranians after the revolution for publishers and for writers who needed some way to understand Iran or themselves. It was bound up in the loss of connection to Iran, in my opinion–the rather abrupt and decisive ways that women were cut off from Iran as a result of the revolution’s aims to change that society. And that severing, that not seeing oneself in Iran, and not seeing oneself here, I think it was much more acute for women. Maybe it is always more acute for women?

Let me say that there are more Iranian American writers now than there were even five years ago. I am glad about that, and I think there will be many more very soon. I think the proliferation of MFA programs will also produce a proliferation of ethnic writers including Iranian American ones. But I do suspect women’s success has paved the way for men, and as we have more and more people entering college, feeling more confident about their identity, their solidity as Americans, as the pull and push of being Iranian American has settled more in all of us, we’ve begun to let those stories out. Men may have not felt the urgency to write as women did in the aftermath of the events of 1979. It might also be that the new languages that came with migration, exile, alienation, had been sitting on the tongues of women for a lot longer. In a way I believe that men always take their privileges as writers, as artists, as people who can express themselves more for granted, simply because of the tradition of male dominance in all cultures. But this may have been the moment when Iranian American women saw themselves being written out of history on the canvas of Iran and the canvas of the US, and so, they chose to write themselves.

Published in America and in English, this anthology has a clear relationship with American literature. Do you think it fits more with ethnic literature of America than with Iranian literature? How do you see it in the context of Iranian literature?

I think there are elements of Iran and Iranian literature in Tremors, for sure, but I see this collection more as a manifestation of Iran and Iranian-ness in the imaginings of this geographical and historical moment in North America. I see this anthology as a cousin longing to reach back and speak in the mother-tongue, but finding its own mother-tongue in the process. And so, I think Tremors is a bit more like a ripple of Iranian literature on the big ocean of Iran’s larger story. I think anthologies are important and interesting but they are more like a doorway than a pillar–they open the terrain rather than cementing it. I hope some day that Iranians can and will be able to read this–whether translated in Persian, to see how we, the writers, carry some of the old stories inside us, and how we make some of those old stories alive in a new language and a new moment. I also think there will be a sense of non-recognition too. How could it not be otherwise? Cultures do not stay the same, but they evolve and marry, and divorce, and make new offspring that carry traces, essences of the past. That is what interests me more than anything.

You have talked in the interview with World Literature Today about the effect of censorship on Iranian literature. Censorship aside, how else is the work of Iranian American fiction about Iran similar or different from Persian literature written outside or inside Iran?

It’s honestly difficult for me to say. I think being freed from censorship (not completely, of course, as we do experience self-censorship, censorship from the publishing industry that tells us what is acceptable, etc.), is one way that Iranian American literature might be different. I think if we are to think of some of the most important Iranian writers who left some of the biggest imprints on that literature, Mohammad Jamalzadeh, Sadegh Hedayat, Forugh Farrokhzad, we might see similarities. These are writers who are both borrowing and incredibly unique. They are not afraid to borrow from other writers, other traditions, as well as break the traditions of their time. They tackle challenging and controversial issues, bring their alienation and exilic sensibilities into their work, and they put themselves into conversation with their audiences. I believe that many of the writers in Tremors and in the still nascent Iranian American body of work, are doing similar things. They’re trying to figure out how to be good writers and write passionately about the things that are important, but also perhaps risky too.

As an Iranian American writer and translator, I have been concern that Iranian American writers are becoming the native informant for Iran and Iranian people. Iranian American literature gets more attention and is published by more prominent presses. I am also concern that maybe the ethnic American narrative has taken the center stage and that the Iranian American writers are displacing the interest to translate and publish works written in Persian and in Iran.

Do you consider these issues of any concern? Do you believe Iranian American writers should take a more active role in engaging Persian literature? (For example, Porochista Khakpour wrote the introduction and has promoted the reissuing of Sadegh Hedayat’s classic The Blind Owl.)

I agree that some Iranian American writers, particularly the ones who don’t speak or read much Persian might have been asked to speak for or represent Iran. It happens to me all the time–people think I follow the daily news in Iran, and I don’t. I can’t. My Persian is just not good enough, and truthfully, I’m not culturally literate enough about Iran to speak with any expertise about that country. Many of us aren’t.

I believe we can do more to promote translation, particularly, the necessity of translating Persian literature to gain more cultural understanding between Iran and the US. I certainly think we shouldn’t blame writers, but rather the publishing industry, and a culture here in the US that seems to treat translation as the bastard child of writing. How do we get back to that place where we engage Persian literature (and there is so much and such a long tradition to engage)? Perhaps we must do more to collaborate with contemporary Iranian writers, and if we can, work around the sanctions and other impediments to publishing. Perhaps more collaborations between native speakers of Persian and more culturally literate native speakers of English, such as Iranian American writers, might help in this endeavor. I think the tendency to blame writers is not a good practice, and that it’s better to figure out ways to fill the great need for engagement. That’s a hunger many of us have.

In the third section of Tremors you include writing that focuses neither on Iran nor on experiences that are distinctively Iranian American. This section might challenge and frustrate the reader’s expectations.

Can you talk more about the decision to include these selections? For example, were you just making a point or do you think there is a deeper dialogue between this third section and other two parts of the book? Are these writers using these stories as a distancing method to deal with topics that can be recognizable as pertinent to Iranian American experience? Is there something that ties this section together beside the fact that its authors are Iranian American?

Many of us feel that our experience of being bicultural, tricultural, or simply growing up between continents and cultures has given us a kind of double-vision. I think of this as being a kind of third eye in which to see others, and in particular to see “otherness.” Anita and I decided that there was something that spoke to us in these stories that is part of that experience of navigating cultures, being set apart from American culture, and not being fully immersed in Iranian culture.

Ironically, each of the authors in this section has one Iranian and one American parent, which for many of us, has been a kind of sub-category in the Iranian American experience. When I was younger I saw this as a deficiency, to not be fully Iranian, not having grown up speaking Persian, not having lived in Iran, but later, I began to see it in terms of how it gave me a much richer perspective, a way to see and encounter otherness in others, with compassion, empathy, and maybe sensitivity. We thought that these stories spoke to that experience, and also the idea that maybe our Iranian-Americanness, or participation in a culture that has been vexed by political challenges for three and a half decades has also made us have to look elsewhere for comfort, for belonging, or even for that strange sense of alienation and risk that seems to be at the heart of many artists’ impulses to create new worlds in literature, music, or visual art.