1. Cornell as Poet

Even if Joseph Cornell’s artworks—his signature “shadow box” constructions, his montages (what he termed his two-dimensional collages), and his films—are visual, not literary, Robert Motherwell, abstract expressionist and friend and pen pal of Cornell, claimed that “his true parallels are not to be found among the painters and sculptors, but among our best poets.”

I’m a poet. Maybe not one of “our best poets”—more of the frustrated, what-am-I-supposed-to-do-with-my-new-MFA, whatever-dude-my-mom-loves-this-poem variety—but a poet nonetheless. And if Cornell is, even in his “completely plastic”[1] way, one of us, then I want to know what he can teach me about poetry writing. I want to be a student of Cornell’s obsessions.

“And what obsessions!” writes Motherwell. “Birds and cages, empty cages, mirrors, ballerinas and theater folk (living and dead), foreign cities, Americana, Tom Thumb, Greta Garbo, Mallarmé, Charlie Chaplin, neglected children, charts of the stars, wineglasses, pipes, corks, thimbles, indigo blue and milky white, silver tinsel, rubbed wood, wooden drawers filled with treasures, knobs, bright-colored minerals, cheese boxes (as a joke), wooden balls, hoops, rings, corridors, prison bars, infinite alleys—the list is endless.”

2. Utopia Parkway

The oldest of four children, Joseph Cornell was born on Christmas Eve, 1903, in Nyack, New York. Cornell’s father, a woolens salesman turned textile designer, died when Cornell and his siblings were still young, in 1917, leaving the family in a financial lurch. Cornell’s mother, however, managed to send Joseph away to school at Phillips Andover that same year, where he stayed until 1919, when he returned home (though home, by this time, was Bayside, Queens), having failed to receive a diploma. Cornell began to work to support his family. From 1921 to 1931, he sold woolens samples door-to-door in Manhattan. During this time he began to frequent galleries, the opera, the ballet, and the movies; he began to accumulate trinkets and scraps, including photos, books, records, and theatre, dance, and film memorabilia.

This period in his life also saw his conversion to Christian Science, which was prompted by a healing experience in 1925. In his stunning homage to Joseph Cornell, Dime-Store Alchemy: The Art of Joseph Cornell, Charles Simic writes: “It ought to be clear that Cornell is a religious artist. Vision is his subject. He makes holy icons.” (In this way, we might consider his lifelong obsessions as a kind of devotion.) Motherwell on Cornell’s religion: “Who would have thought a puritan would have so much sensuousness and richness of images?”

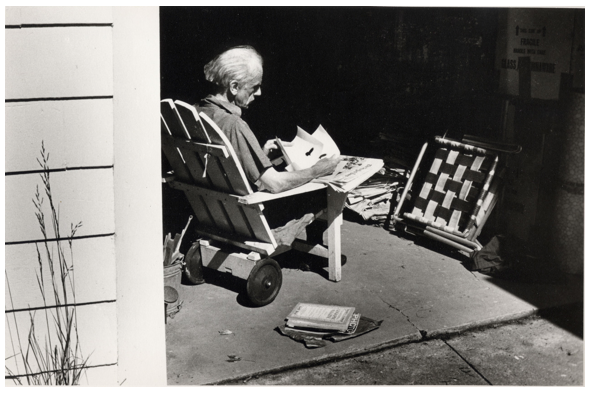

In 1929, Cornell, his mother, and his invalid brother, Robert, moved into a white frame house on Utopia Parkway, Queens, where they resided together for the duration of their lives. (Robert passed away in 1965. Their mother, the next year. After that, Cornell lived alone in the Utopia Parkway house until his own death in 1972.) In the basement of this house, Cornell constructed his boxes. In its oven, he often baked them—putting in a new object, pulling out an “antique.” And outside the house, he would “christen” finished boxes by placing them in sunlight. Cornell’s work first appeared in a gallery in 1932—story goes, in 1931, a few weeks after spying gallery owner Julien Levy unloading surrealist objects, Cornell presented him with his own work, his montages, and Levy, it seems, was quite pleased.

3. Homage to the Romantic Ballet

I want to be a student of Cornell’s obsession with ballet.

Though Cornell saw Anna Pavlova perform not once, but three times (three!), during her 1924-1925 farewell tour in New York, his interest in ballet turned into obsession in the 1940s, after meeting Tamara Toumanova, a Balanchine ballerina and one of Cornell’s lifelong muses, at the beginning of the decade. In 1941, he began to construct a series of boxes devoted to her and titled Homage to the Romantic Ballet. He even mailed one of these “souvenir” boxes, Homage to the Romantic Ballet (Dream Fragments), to Toumanova in Hollywood on March 26th, 1941. Inside this particular box, below a picture of Romantic era prima ballerina Carlotta Grisi, reads the following inscription: “Dream fragments loosened by the breezes from the floating form of the fairy, Carlotta Grisi. Gold rain shed from the garments of the dark fairy, Tamara Toumanova in the ‘Nutcracker Suite.’” That same day, Cornell acquired five New Yorker magazines, each for its image of Toumanova.

Cornell loved ballet’s Romantic era and its prima ballerinas, ballerinas like Carlotta Grisi, Marie Taglioni, and Fanny Cerrito, all of whom he featured in his work throughout his career. He read widely on them and the era, amassed Romantic ballet photos, letters, and memorabilia. Once, Fanny Cerrito appeared to him in a vision. From his diary:

All day long, week in-week out, I look across from my studio table at the forbidding drab gray façade of the huge Manhattan Storage and Warehouse building with its symmetrical row after row of double metal blinds, every night, promptly at five, uniformed guards appear simultaneously at each of the myriad windows drawing in the ponderous rivet-studded shutters for the night. But this summer evening at the appointed time the ethereal form of Fanny Cerrito, breathlessly resplendent in gossamer of ondine, appears in each casement to perform the chores of the guards. So guilelessly, with such ineffable humility and grace, is the duty discharged as to bring a catch to the throat. Her composure and tender (slow fade-out) glance rebuke regret as she fades from view.

Cerrito fades like a ghost, like a shade. Obsess. A rare usage of obsess denotes haunting, torment, the control of an evil spirit over a person from without. Cornell was obsessed with Fanny Cerrito, by Fanny Cerrito. She haunted him and his work. Consider the thorough and meticulous mixed media “explorations,” together called Portrait of Ondine, he based on her famous role as the naiad Ondine.

The lesson? Exploration, indulgence, obsession.

I’ve had interests, but obsessions? I want them. I want to memorize an entire book of poems. I want to read every text I can find on Victorian photocollage. I want giant reproductions of Florine Stettheimer’s paintings pasted to the ceiling above my bed. I want to listen to Mingus Ah Um again and again, until I can’t tell if the music’s coming from within or without. I want to be starstruck. I want to write fan letters to my favorite writers, dancers, and artists. Cornell after all, as Simic notes, “sent gifts of scraps of paper and odd objects to ballerinas he loved.” I want to be consumed. In my pursuits, I want to be exhaustive and tireless.

But do I want to be haunted? There’s risk involved. Over-indulgence. Humiliation. Cornell worried—from his diary, dated October 3, 1949: “thoughts of meeting ballerinas and of loss of contact with those [ballerinas] who have seen my objects in galleries.”

And do I want to haunt those whom I love? Cornell imposed himself on the dancers he adored in a way that wasn’t entirely platonic. Take, for example, the time he asked New York City Ballet dancer Allegra Kent, a longtime friend of Cornell whom he met in 1957 when she was 19, to bring him a book on erotic art. (She did, along with a mocha cake.)

Cornell’s relationship to women was fraught. He idealized the women and girls he adored. Not just ballerinas, but movie stars, the daughters of friends whom he sent collaged letters, the “fairies” or “fées” he encountered on his outings to gather material for his boxes. (I wonder, do all obsessions result in this kind of idealizing? Does an obsession necessarily become a fetish? Does obsession lead to trouble?) Though eros is at play here, Cornell valued celibacy; in an 1954 diary entry titled La Sylphide, he writes:

…consideration of types of universal genius who never married or remained celibate—a healthier sense of love than is thought possible these days….Celibacy prevents the squandering of emotion that is better employed in working on a box, or that exaltation of the eye and spirit that he is able to feel in his early morning bicycle rides.

And yet, he loved pornography, though he tried and failed to avoid it. From his diary, January 12, 1960: “…—skirting obsession with magazines in ‘another area’ but an image lingering graciously.”

Obsession, like desire. Obsession, just like constant, long-term, insatiable, patient desire—which is, of course, the very heart of art and poetry.

4. Echo Chamber: Cornell teaches me rhyme

Take, for example, Taglioni’s Jewel Casket (1940), named for Marie Taglioni, the ballerina whose en pointe, tarlatan tutu-clad performance in La Sylphide (Paris Opera, 1832) marked the birth of ballet’s Romantic era. Inscribed inside the box:

On a moonlight night in the winter of 1835 the carriage of Marie TAGLIONI was halted by a Russian highwayman, and that enchanting creature commanded to dance for this audience of one upon a panther’s skin spread over the snow beneath the stars. From this actuality arose the legend that to keep alive the memory of this adventure so precious to her, TAGLIONI formed the habit of placing a piece of artificial ice in her jewel casket or dressing table where, melting among the sparkling stones, there was evoked a hint of the atmosphere of the starlit heavens over the ice-covered landscape.

I love Taglioni’s Jewel Casket for its echoed forms: the perfect rhyme of the glass cubes, each in the set of 12 just like the last. Cornell teaches us slant rhyme, too. The cubes are echoed imperfectly in the shape of the very box that contains them, in the string of smaller gems that hangs above them, in the negative space into which they fit. Here, absence (the square cutout) becomes presence (the shape of a square), just like a ghost. In this way, this box—the dead ballerina’s jewel casket—is haunted.

And what is returning to something again and again—be it word or object, sound or form—but obsession?

Cornell was deliberate and craft-conscious regarding form, but wild, playful, intuitive, obsessive, dreamy, and magical when it came to content. “Did Cornell know what he was doing?” Simic asks. “Yes, but mostly no. Does anyone fully? He knew he liked to see and touch.”

5. Creative Filing

In the 1950s, Joseph Cornell’s collections—archives, hoards, scraps—became overwhelming and he hired assistants to help him sort, order, and organize the accumulated materials.

The first stages of writing often parallel this process of accumulation. The uncensored collection and hoarding of words, sounds, notes, lines, variations on lines, ideas, images, etc. And so often, the final stages of writing feel like organizing, ordering, and sorting. We ask ourselves, What do I have? What should I keep? Where should I put it?

On March 9, 1959, Cornell wrote:

Creative filing

Creative arranging

as poetics

as joyous creation

6. Coda

Motherwell: “His work forces you to use the word ‘beautiful.’ What more do you want?”

Simic: “Beauty is the improbable coming true suddenly. The great ballerina, Emma Livry, a protégée of Taglioni, for instance, died in flames while dancing the role of a night butterfly.”

This night butterfly as an image of the poet, the student. Skittish, moving through the dark, aloft, with white paper wings.

[1] Robert Motherwell. See Joseph Cornell’s Theater of the Mind: Selected Diaries, Letters, and Files for the complete essay from which I’ve gathered his excerpts.

Photo Credits: Harry Roseman, www.josephcornellbox.com, Smithsonian American Art Museum, loveisspeed.blogspot.com