In November, I watched the National Book Awards award ceremony via an online broadcast. I’ve never been one for awards ceremonies—they’re long and boring, and the fabricated glamour of it all wears thin when I’m wearing sweatpants and a soup-stained t-shirt—but a U of Michigan alum of 05’, Jesmyn Ward, was nominated for her novel, Salvage The Bones, and if she won, I wanted to witness it. Of course, my impulse to watch the awards was a self-involved, highly illogical one: that if I am a U of Michigan MFA Fiction student and she is an alum of this same program, then I might be able to produce a work of similar notability and talent, or perhaps at least one day, someone might publish my work (if I ever finish it), sweatpants and all. When she won, I was surprisingly elated. As if I had won too. I bought her books, the hour after, not yet critical of why it hadn’t occurred to me to buy them before.

I’d read public reactions to the nominations before the award show, most notably Laura Miller’s article on salon.com wherein she explored “the ever-broadening cultural gap between the literary community and the reading public.” Miller criticized the judges for routinely choosing obscure titles, arguing how this practice makes the NBA irrelevant, no longer a good indicator of what the American reading public enjoys nor what they might enjoy.

I myself only knew vaguely of the nominees (the exception being The Tiger’s Wife by Tea Obreht). And the reason for my ignorance is obvious: there are so many books being published nowadays, and not enough time to read them all. Shamefully, awards like the NBA help us sort through that pile to the ones we presume must then be worth reading. As an author, Ward had been drifting along in relative obscurity, compared to big name authors like Jeffrey Eugenides, who failed to make it to the shortlist. Ward postulated in a recent EW interview that perhaps her characters and settings explain why she’s not the most well known author: “I think people make certain assumptions about what they’re interested in reading or what others would be interested in reading, and when they think of poor black people in the South, they don’t think people are interested in reading about those people.” Her first book, Where The Line Bleeds (2008), is about twin boys in Mississippi whose struggle to survive sends them in two disparaging paths. Salvage The Bones (2011) also follows a Mississippi family, this time, days before Hurricane Katrina. I see her point, especially considering the literary marginalization of authors of color.

As a person who writes about poor black people, I am worried, too, about how my work will be received, if my book will survive the reader’s casual glance at the blurb. I am grateful that awards notice these disadvantages and look to nominate books of literary talent, regardless of public popularity. Especially since this has not always been the case, for any author who writes transgressively or experimentally about cultures different from what attracts the average reader. But of course, for every Jesmyn Ward, there are many other writers who are writing about places and people that the general reading public never encounters. What about those books that are not being validated by an award, but are still of exceptional talent?

Now that the wave of elation has left me, the self-congratulation (self-assuredness) that can sometimes occur when we know, have read, have defended a book that has been awarded a literary prize, has watered down, I’m left unsettled, with a suspicion that I have completely missed the lesson Ward’s win could teach me. I’ve become a complacent reader. Most readers are, with so little time to dedicate to the task. Because reading can be such a time consuming solitary act, I’ve gotten into this lulling practice of only reading books that have been recognized and validated (inter)nationally so that my time won’t be wasted, so that I can learn the most about the craft. I’m never questioning who those judges are, what criteria they’re using, what assumptions they are making about craft. Why were some books declined? Too political? Too black? Too queer? Too poor?

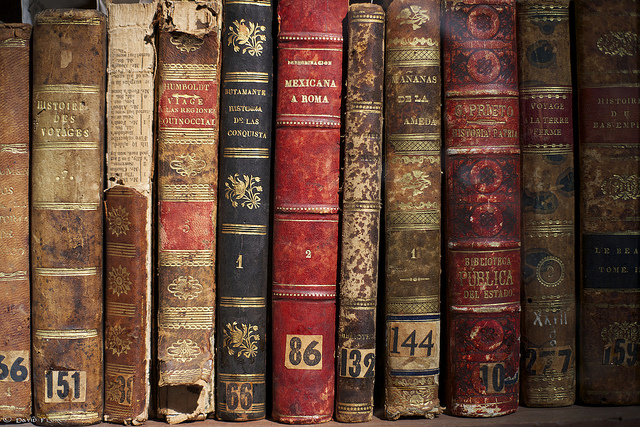

When I was younger, I would go into a library and check out the first book I picked up, before I had a chance to read the blurb or look at the cover or any other trait that I could use to make my usual readerly judgments. Of course, the books were sometimes awful: either too complex for my age, too simple for my age, too boring, too slow-moving. One book was so badly written that I never finished it and clearly no longer remember it. There were books I did enjoy, and remember still, like Bram Stoker’s Dracula. It was a book lottery that I was happy to play, regardless of outcome. My point isn’t to avoid books that have won awards, or the classics, but to read voraciously with no discernment, rekindle again a readerly passion and curiosity, because what I’m doing now can’t be any better. Now I’m not allowing myself to read a book for the most basic reason: that I love reading. And it’s a shame because there are so many books out there by authors who have something to say, who write well, who simply, for many reasons, have never won a national award.

That being said, I wouldn’t mind winning a national award.