For the past two weeks, I’ve been immersed in the commemorative supplements of a Malaysian newspaper celebrating its fortieth anniversary this month. I’ve read every single one of the articles available online, even the sports coverage, even the sex advice straight out of trashy magazines and unthinkable in a Malaysian newspaper today. I’ve lingered over the fonts, the text-heavy advertisements, the hairstyles and sunglasses of the 1970s.

Nobody who knows me would ever accuse me of living too much for the moment. Like the god Janus, in whose month I was born, I have one pair of eyes perpetually trained on the past and another squinting into the future. What is it about old photographs, even old photographs of strangers, that holds me rapt for hours? I think it is partly the gleam of What Could Have Been beneath the surface of the image, what I imagine could have been, what has been lost, what will therefore never be (there it is again, that anxious-making future). I know that memory is a tricky, unreliable thing, as far from objective truth as one can get, but that’s precisely why it’s so interesting to me. Memory is true in the way that fiction is: more true than facts, more revealing, more binding when shared.

As sure as I am that my memories are an inaccurate record of my history, I’m deeply attached to their abundance and their rich detail. My husband has very few memories of his childhood: ask him what he thought about a teacher or a television show or a colour when he was five, six, seven years old, and nine times out of ten he will say he doesn’t know. Of course the truth is that I may not actually know what I thought either, but for whatever reason, my brain offers me answers to these questions and his does not. My husband’s way of being in the world, of relating to his surroundings, is completely different from mine in this respect; sometimes I think that he is happier — less tortured by regret, at least — because of his sparse memories.

Because I constantly revisit most of my memories — analysing them, talking about them, writing about them — I’m not used to being surprised by memories I didn’t know I had. But scientists tell us that the more often we retrieve a memory, the less accurate it’s likely to be; in other words, each time we recall and even and then file it away again, we modify it a little in the refiling process. It’s possible that my husband’s unaltered childhood memories are somewhere deep within the labyrinth of his brain, a thousand times more accurate than the stories that shape my adult opinions and decisions.

On the day the Star newspaper launched its commemorative website, my eye fell upon a tiny image of a woman’s face on a front page more than thirty years old, next to the headline: EX-BEAUTY QUEEN SLAIN. Seeing just that blurry photograph of the woman’s face, a wealth of information I didn’t know I’d stored away came back to me: her full name, the name of the accused, certain other images of her from other newspaper reports, the official version of the story, the hearsay, the gossip. She is, I now realise, one of my earliest memories of the world beyond the doors of my childhood home, and her name must have been one of the first names to register in my consciousness without belonging to a relative, friend, or character in a favourite story. If you wanted to, you could easily trace her name and her face. Beauty queen, murder, Malaysia, 1979. So I’m not sure why I cannot bear to type her name out here, why I feel something akin to loyalty to her and her family. If I really wanted to respect their privacy, I wouldn’t be writing about her at all; I would be letting a long-dead story lie instead of holding it up before you so that you and I may better understand the tiny Preeta Samarasan and the woman she became. After thirty-two years, the Star newspaper seems to have felt no need to tread delicately around the story; surely everyone involved must have moved on, surely there could be nothing so wrong with using that sensational headline to promote their fortieth-anniversary supplements.

The names are the only part of the story I cannot bear to write here. I will tell you that the murdered woman was pretty, glamorous, perhaps even beautiful, as you might expect from her ex-beauty-queen status. I remember hearing this repeatedly — so pretty, very pretty, beautiful girl — and studying the photographs in the newspapers to figure out for myself what these words meant. I will tell you that the woman had been recently widowed, and that she had left her three young children at home for drinks and dancing with her late husband’s brother. In 1979 in Malaysia, I didn’t know any other women in my parents’ generation who went out drinking and dancing. Certainly men went out drinking, but if they danced as well — at nightclubs, with women not their wives — this was something only alluded to in whispers. The murdered woman was what my parents and their friends called the party type, hot stuff, fast, and not just because she had been out drinking and dancing at a hotel, but because she was not faithful to the memory of her husband, not continuing to mourn him while raising his children. They didn’t say she’d deserved what had happened to her, but I understood that they were not completely surprised: they believed that when such horrific crimes happened, women like her were usually the victims, not the good girls, not the homely types.

Suddenly confronted with the woman’s picture two weeks ago, I found I didn’t remember her children’s names, but I did remember that there were three of them, one of them exactly my age. I must have been struck by this detail at the time: that girl is my age. The woman and her brother-in-law had been househunting together earlier in the day; they were to be married the following week. That part, too, I hadn’t remembered, but I remembered the woman’s blood-spattered white car on the abandoned road, the woman dead in the passenger seat, her saree soaked in her own blood. I remembered the brother-in-law lying unconscious behind the white car.

What does it mean that I “remembered” these images? Probably that I’d constructed them from snatches of adult conversation. All I can say for sure is that, reading the republished newspaper account a few days ago, I found my brain making a clear distinction between the details I already knew and the details that were new to me. I remembered my parents and all the other adults I knew being convinced that the brother-in-law, accused of the crime, was guilty; I remembered them calling it a crime of passion, of jealousy. But I had somehow forgotten the purported object of his jealousy: the mysterious Sri Lankan lover, who had met the woman on a visit to Malaysia, and whose name I now learned for the first time. His letters to the dead woman were so explicitly erotic — according to one of the journalists who covered the case — that they were not reprinted in the newspapers out of consideration for the woman’s children: god forbid that they should grow up and one day discover that their mother had performed these acts with a man to whom she had not been married.

I think I can safely assume that most other writers would have done what I did and Googled all the players in this drama. Writers are indiscriminately curious about other people; we want to know everything about everybody, and we want to know it right now. We want at all times to know more about other people than they know about us. I can list for you — like the ending of a bad made-for-TV movie — where all these characters ended up: the accused was acquitted, eventually married someone else, and remains married (“happily married,” according to one source) to her in a small town outside Kuala Lumpur; the secret lover served a term as dean of the faculty of medical sciences at a university in Sri Lanka; the woman’s three children grew up, took new first names, and have been successful in their chosen careers. One is a lawyer; she and I have a Facebook friend in common. Malaysia is a small country, and the world of middle- and upper-middle class Malaysian Indians is tiny, crowded with lawyers and doctors.

Out of everything I had forgotten and everything I had apparently remembered, one thing continues to surprise me: that I did not — at least not consciously — recall this murder when a close friend of my own was murdered eight years ago. My friend’s life, too, ended in the passenger seat of her own car, or close to it, at any rate — the forensic evidence could not confirm the precise moment at which her life ended. Like the ex-beauty queen, my friend was pretty and glamorous. Some thought of her as the party type, hot stuff, fast. That, at least, was how she was portrayed in the media by those who covered the case. But as far as I know, the media drew no comparisons between these two high-profile cases, probably because of the great length of time that separated them. When I realised that I had lived through the days of my friend’s disappearance, the weeks following the discovery of her body, the months of the investigation, and the years leading up to the court case without once thinking of this earlier murder, I felt almost betrayed by my memory, this memory I trust not to tell me the whole truth and nothing but the truth, but to throw up reflections and associations in response to every little thing.

If I had remembered the murder of the beauty queen, would I have experienced my friend’s death differently? If the science is correct — if it is true that the more rarely you remember something, the closer your memory remains to the reality — the people and the experiences most important to us are the ones we remember least accurately. The more you try to hold on to a memory, the less of it your brain preserves. You could think of this as the cruelest among nature’s many cruel tricks, but in this particular case, I don’t know whether my memory failed me or protected me. Maybe it’s a small mercy that the details of my friend’s murder have been changed, in my mind, in ways I will never know, while the murder of a woman I never knew remains as fresh this week as it was thirty-two years ago, unfolding before my wide eyes.

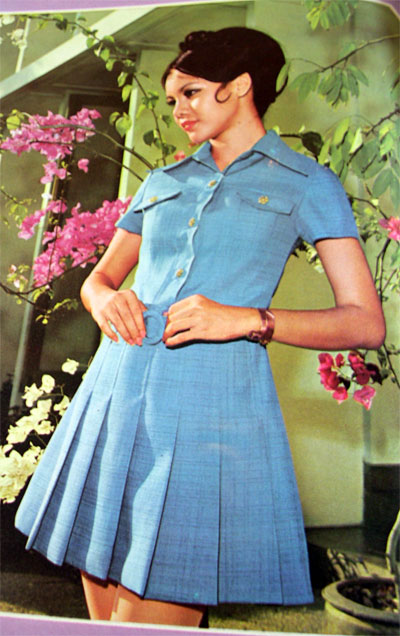

Photo credits: 70s girl by Preetam Rai on flickr; Janus by Thierry Ehrmann on flickr; 70s memories by Eve D. on flickr; N 6231 Patons Piccadilly by James Paterson Art; Nostalgia Saturday by Leandro Pérez.