Over the last few weeks, I have been following the social media posts of Iran’s Minister for Foreign Affairs, Javad Zarif. Much has been written on the vital role of social networking during the Iranian Green Movement — how it helped to organize people and disseminate information. The Green Movement was even called the first Twitter or Facebook revolution. In the aftermath, Iran banned these sites, which probably reinforced their importance. I don’t want to rehash what others have already said — the role of social media in Iranian politics has been exaggerated — but I am interested in the innovative and progressive ways Zarif has been able to turn these banned tools into a resource for the government. What seemed to be a revolutionary venue outside of the regime may be re-purposed into a pathway for reform from the inside. Reading Zarif’s Facebook page lets you know more about the Iranian people than any article in an American or Iranian newspaper. It is like eavesdropping on conversations in cafes and streets. As this conversation unfolds in Persian, allow me to translate it for you.

You might have heard about Zarif’s Twitter exchange with Christine Pelosi, daughter of House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi. After his tweet of “Happy Rosh Hashanah,” Ms. Pelosi responded, “Thanks. The New Year would be even sweeter if you would end Iran’s Holocaust denial, sir.” Zarif answered, “Iran never denied it. The man who was perceived to be denying it is now gone. happy new year.” That “man” was Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, and Zarif pointed out that Hassan Rouhani had succeeded him as president. Yet the Western press still questioned the authenticity of the poster.

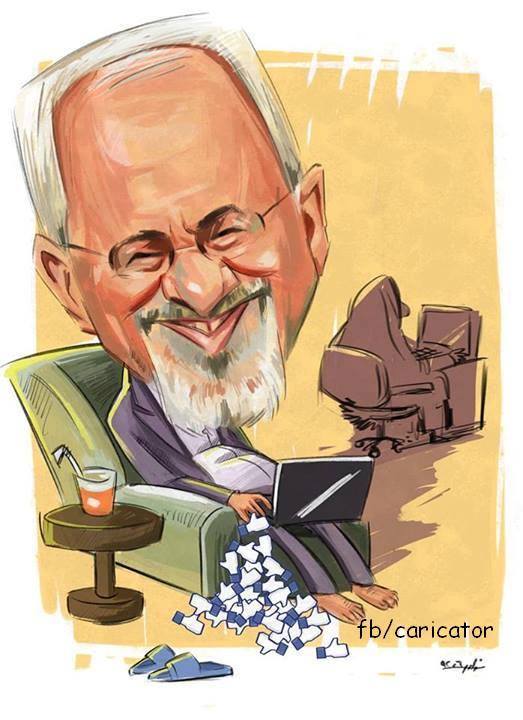

The tweets, in English, are meant to be read by the world outside of Iran, but Zarif’s Facebook page is intended for the Persian community both inside and outside Iran. It has opened a personal communication channel between a government official and the people. But unlike the Facebook pages of other Iranian leaders, including President Rouhani, his page presents a “real” person interacting with “friends.” Zarif writes intimately to his visitors. His posts touch on simple matters like getting caught in traffic, not getting enough sleep, or how jetlag has allowed him to spend more time with others on Facebook. He wishes “Happy Daughters Day” to Iranians and to his own married daughter, and he even includes a caricature of himself. Like many Iranians, Zarif quotes lines from iconic poets, such as Ferdowsi and Rumi. He even uses poetry for his Facebook cover: The lines by Ferdowsi — “Try to bring forth goodness. / When you see frost, think Spring.” — were mentioned in Rouhani’s recent speech to the United Nations.

Zarif reports on what he is doing and where he has been, including documents, pictures, and links to events. He lists the people with whom he had lunch or dinner in New York, noting his “good friend of thirty years” Kofi Annan, the former U.N. Secretary General. A man commented that Zarif’s reports were better than the ones he gives to his boss. He asks his readers to wish him well and pray for a good outcome. He thanks them for their feedback and even answers comments. When the feedback reaches thousands of personal messages, he apologizes for not being able to respond to most people, saying how he doesn’t want to hire an administrator, because he wants to keep his direct connection with everyone. He also asks for politeness and says he may delete messages that insult or mock individuals, groups, organizations, ethnicities, or religions. Though as it stands, possibly because of the number of comments, much on his page is uncensored. In fact, readers act as moderators, answering questions and reprimanding those who mock and insult.

This intimacy and openness has led to the page’s great popularity. It already had 284,031 likes as of September 25, with 184,987 “talking about it.” Followers grow by the minute. Ten thousand joined since yesterday. Compare that to the Facebook page of the much-loved Mir Hossein Mousavi, the 2009 presidential candidate, who has 333,695 likes with 8,733 talking about it. Mousavi’s page has been active since January 19, 2009, and often includes English translation. Especially during the Green Movement, many non-Iranians liked his page. Zarif joined Facebook on February 14, 2009, but his page appeared to have been inactive, with no posts before August 10, 2013 (I am not sure if he deleted earlier posts).

One, of course, can argue that, given the political situation, Iranians may be afraid of liking and commenting on Mousavi’s posts, though they get about 1,000 likes and 100 comments. Zarif’s posts, on the other hand, have attracted as many as 50,000 likes and thousands of comments. That’s remarkable, especially when you consider that Facebook is still banned in Iran and most Iranians use filter breakers to access the Internet.[1] Zarif’s numbers are much higher than President Rouhani’s Facebook page, which is more official and doesn’t provide the same platform for open dialogue.

Both men and women responded freely to Zarif’s posts while knowing full well that the page could be monitored. People often comment on each other’s posts, forming a virtual public square for debate and commiseration. Some comments get as many 100 replies. For example, when Adam Dean Cameron, an American, wrote that he loves Iran and wants to visit but can’t get a visa, Zarif responded that he hoped to meet him. The exchange then grew with more than 280 Iranians talking directly to Cameron, giving him advice, telling him where to visit, inviting him to their homes, warning him about the economic and political condition in Iran, congratulating him on his skill in Persian, correcting his Persian, joking with him, and praising him. When some wondered whether he is a spy or is just trying to get attention, others chastised the accusers.

There is a great deal of familiarity, freedom, and openness to these posts. Zarif brings out a genuine sense of pride and hope. Readers are excited that a representative is directly talking to them and seems to care about their opinions. They talk to him as a friend, wishing him well, calling him “dear Javad.” They speak about how he looks and how he may have gained weight. They ask him questions. Many mention that he is their favorite minister, their best hope.

It is an emotional experience for me to read all the comments. People write about their personal and political wishes. They share their struggles. One talks about his hardship at work and the difficulty of paying bills. Another talks about a police arrest and intimidation. And another talks about the difficulty of traveling with an Iranian visa and the disrespect they experience when abroad. They give him advice, sometimes with long comments. They ask him to free Mir Hossein Mousavi and other political prisoners, to work to remove the economic sanctions, to bring democracy, to alleviate their struggles, to make Iran proud, and to make Iranians respectable in the world. They joke with him. One asked him to tell Rouhani to pronounce a word correctly. They exchange lines of poetry. A sense of genuine love — complete with many emoticons — overwhelms the comments. When his page was hacked and he said he might have to close it, the outcry was quick and strong. Over 5,000 comments pleaded with him not to cut his connection to the people, arguing that this is exactly what the hackers wanted.

So far, Zarif’s page remains an open platform, a true social network in a quasi-governmental space. Conservatives and liberals talk to each other, debate, and argue. Some attack Zarif, Rouhani, and the Islamic Republic, and these comments have not been deleted. Others say that people like Zarif because he doesn’t have a turban and a long beard. They ask for results, not rhetoric. They complain that things don’t get solved with poetry. They question the hypocrisy of him having a Facebook account when Facebook is banned in Iran. They ask what filter breaker he uses. Some even call his government a dictatorship responsible for mass murders, comparable to Hitler, and the responses offer diverse perspectives. Commenters share concerns and grievances, exchange personal information, and remark on foreign policy, censorship, the holocaust, nuclear energy, and the U.S., Russia, and Syria.

Zarif has found a way to take this medium and make it a force for democracy in a way that no other leader in Iran could have imagined. I am not sure of the ultimate value of social media, and I have never liked the page of a government official, whether Iranian or American. My interest is art and literature. But Zarif is the first official I have “liked,” because I believe if a government representative can open dialogue with his people and report to them, if he behaves like a fellow citizen, if he provides a platform where others can openly share their ideas and experiences without fear, if he treats others with respect, then he deserves praise and respect.

————————-

1. Government officials and some organizations enjoy unfiltered access to the Internet. While filter breakers are technically illegal, they can be purchased (how well they work varies), and the Iranian government generally looks the other way. I have many Facebook friends who live in Iran.

[All images are from Javad Zarif’s current Facebook page (Sept 25, 2013).]