I’ve been learning German off and on for almost two years now, and sometimes the language seems to have batted its pretty eyes at me and turned away. Like any doomed pairing worth its salt, we share an irreconcilable incompatibility: I’m precise when precision is important, but at a point I leave stray details alone so that I can read and sleep and stuff. Unfortunately, German requires its learners to be always on duty with an unerring, unflagging attention to detail. The grammar is so involved that I’ve started to suspect you have to practice it from birth to have any hope of mastering it[1]. Strictures of word order plague beginners whose verbs are always burning off like fog before the end of a relative clause, while the chicaneries of declinations ensure that it’s almost impossible for even an advanced learner to string together, say, three perfectly accurate sentences. There’s probably a German proverb that speaks to the shame of overcomplicating a thing that could be simple, but no one has taught it to me yet. All the native speakers I know are too busy hin-ning and her-ring, heraus-ing and hinauf-ing away. To listen in on this is to entertain visions of the nimblest governess running to and fro in an Alpine wonderland, and then to admit that The Sound of Music made too deep an impression, and then to suspect an impending seizure if you have to listen much longer.

The trouble starts with the old story of articles. German’s arbitrarily gendered “der,” “die,” and “das” assault non-native speakers with bothersome extra work (feminine; die Arbeit) from beginning (masculine; der Anfang) on. A language learner might decide that learning the word for floor, Boden, is enough and not care that it is masculine[2]. This learner is condemning herself to future mistakes across the cases and into the general hoopla of adjectives, which must agree with a noun’s case and gender according to a system that causes even the best teachers to consistently postpone the lesson just one more day. Adjective endings appear to be a German language trap designed to ensure that even the most schooled and enthusiastic latecomer will get excited and give themselves up over something beautiful or amazing sooner or later.

The difficulty of mastering the cases themselves pales in comparison. It’s jarring that the feminine “die” must be replaced with the masculine-looking “der” when a “feminine” thing, idea or person is the object of an action or otherwise datively engaged. But really this just means that you have to memorize the cat (die Katze) when it is identified and not when it is given something (zu der Katze) or when something is sitting on it (auf der Katze). The case system does eliminate some prepositional pile-up. That’s a cause that we should all get behind, but then one of them (the genitive) is by some accounts dying, which makes it hard to want to learn. Another (the dative) behaves like an indulged child, calling for accommodations including the Allocation of an N to Certain Plurals. Sniff, sniff. Plurals are challenging enough as it is given that there are twelve possible ways for them to manifest. This makes designating multiplicity in German as confusing as facing the wall of jams at Aldi. Eventually you just have to toss something in the cart and get on with it.

But Mark Twain covered all this and more in “The Awful German Language.” Anyone learning German should read this and laugh until crying sweet-bitter tears of understanding. Anyone considering learning German should stay away to avoid a failure of heart. Twain’s essay is alive with a cheeky affection for the language disguised as critique of it, is smart and observant in its reporting on a grammar’s rules and quirks, and is simply a hoot from one sentence to the next. It’s also surprisingly shot through with death and violence, from the early claim that Twain’s German learning experience was “accomplished under great difficulty and annoyance, for three of our teachers had died in the mean time” to the proclamation that if German “is to remain as it is, it ought to be gently and reverently set aside among the dead languages, for only the dead have time to learn it.” Between these morbid buttresses, Twain pens his murderous intentions (on having one pronoun with six meanings: “[W]henever a person says SIE to me, I generally try to kill him, if a stranger;” on compound words: “the inventor of them ought to have been killed”) and lets loose some casualties (two deaths by fire, one of disappointment, one during an imaginary surgery wherein a thirteen syllable word is extracted, plus incidental mention of organ failure and stroke). For all his delight in the language, the essayist also appears to have been carrying a load of resentment.[3]

But Mark Twain covered all this and more in “The Awful German Language.” Anyone learning German should read this and laugh until crying sweet-bitter tears of understanding. Anyone considering learning German should stay away to avoid a failure of heart. Twain’s essay is alive with a cheeky affection for the language disguised as critique of it, is smart and observant in its reporting on a grammar’s rules and quirks, and is simply a hoot from one sentence to the next. It’s also surprisingly shot through with death and violence, from the early claim that Twain’s German learning experience was “accomplished under great difficulty and annoyance, for three of our teachers had died in the mean time” to the proclamation that if German “is to remain as it is, it ought to be gently and reverently set aside among the dead languages, for only the dead have time to learn it.” Between these morbid buttresses, Twain pens his murderous intentions (on having one pronoun with six meanings: “[W]henever a person says SIE to me, I generally try to kill him, if a stranger;” on compound words: “the inventor of them ought to have been killed”) and lets loose some casualties (two deaths by fire, one of disappointment, one during an imaginary surgery wherein a thirteen syllable word is extracted, plus incidental mention of organ failure and stroke). For all his delight in the language, the essayist also appears to have been carrying a load of resentment.[3]

The trials of the German learner go on and on. Tuesday and Thursday evenings fill up with simple sentences about jobs and food. After weeks of practice, the picture still refuses to perform the act of being hung on the wall and then of hanging permanently on the wall in sentences that are both impeccable and spontaneous. Because I’m prouder than I knew, I’ve found the reduced personality that comes with learning to talk again surprisingly bothersome. Any language learner is sure to feel a shadow of the quick-witted and acrobatic conversationalist who looks on from her mother tongue. And the psychic trash of bungled jokes and protracted, embarrassing stories is harder to get rid of than the remains of your typical dinner party. I’ve said things in German that I would never say or even think in English. But mostly I just nod and laugh.

The prescription for language learning success is available from any target language speaker who is better than you. They are everywhere, these experts. As soon as one has scolded you for trying to practice conversation with your partner-partner rather than a tandem partner the next swoops in demanding to know why you haven’t established English-free Fridays. One advisor reprimands you for not taking enough classes and the next, who actually is a German teacher, would have you to know that you’re going about it all wrong: why go to class and try to parse the rules when what you need is conviction and verve? The best speakers, according to this conversation at least, are actors and opera singers because they believe, deeply and professionally, that they actually are German. Or something like that.

One of the most common complaints of the German learner is the difficulty of getting any on-the-ground practice[4]. Try to dig your upper-intermediate conversational hooks into a native speaker and they are likely to politely shift to Zank You. I find this especially hard to take if the other party’s English a little bit terrible, because this makes me wonder if my German is not a developing skill so much as a hellish event. For just ten Euros, this phenomenon comes with a tote bag. It’s fun to match your German-speaking preference to your outfit, but I doubt if it works. There are lots of trite and probably true excuses for English-oriented behavior, but they never consoled me. The most effective strategy I’ve devised for weathering the switch is to tell myself that even people speaking English with me would probably choose another more suited language if that were only an option for us.

And so it goes. And so I continue practicing the Umlaut, deepening the romance, embarking on the upkeep of a relationship even as I’m considering giving up adjectives altogether. I’ll just tell them that I have to verzichten darauf, and they’ll understand. The ü in contrast is a tricky devil always demanding attention, but it looks so sprightly that I want to lumber after it regardless of whether I’ll ever properly pronounce its long and short forms. And so it goes on. I think I’ve reached solid ground with the language and then look out to discover that I’m just on a big rock in the ocean of it. Egal! Any love is sustained by that little bit of mystery, the beckon of a secret that’s almost accessible.

[1] Even that might not be enough. My husband, who is a native speaker, recently looked up from editing his dissertation and lamented, about -em adjective endings, Sometimes I just can’t hear them, which struck me as a cause for both relief and concern.

[2] A friend of mine who lives in Berlin sold a basketball on Craigslist. For some reason, the transaction required her to say to a native German speaker, the floor is crooked. She incorrectly guessed that the floor was neuter, which undermined her authority as a speaker so much that after correcting her the buyer refused to speak one word more in the language. Poor German! Poor floor!

[3] NeinQuarterly on Twitter is the place to go for contemporary commentary in, on, and around all things German language. But he has more than 30,000 followers, so obviously lots of people already know that.

[4] This is less commonly reported, but as an English speaker, I’ve also experienced the reverse: You sit down at a café in Berlin with a Hefeweisen and your dowdy Genglish, and the tableful of philosophers looks at you, smells your fear, and, proceeds full-speed with their witty, sophisticated remarks on Hegel, Hegel. There’s something political to this—and there’s no status to be conferred by sidelining in, or otherwise catering to, a language has been forced on them since birth or age 13. Um, but I would also flounder in an English conversation about Hegel, come to think of it.

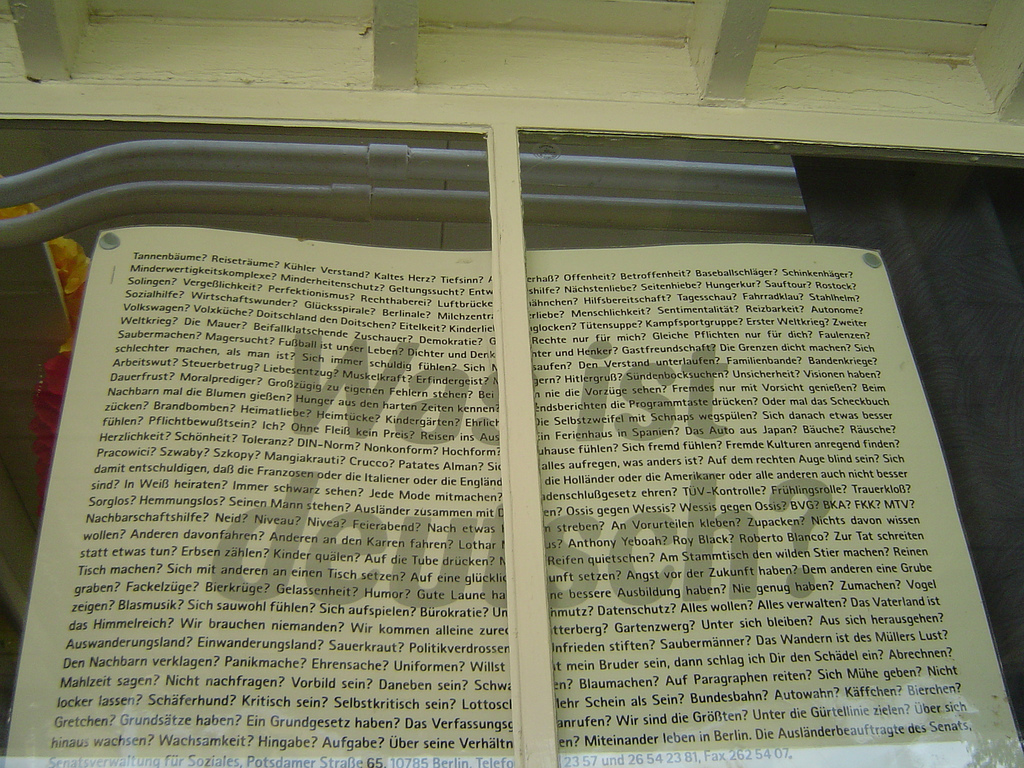

* First image from Flickr user {I’m a scientist}; second image is a photo of Mark Twain from Wikimedia Creative Commons