Short fiction by Peter Ho Davies from our Fall 2011 issue.

They’re going to kill me if they get hold of me.

—Orson Welles

FDR was my boyhood hero—long before the New Deal, as President of the New York City Boy Scouts Association, he’d founded the Ten Mile River Youth Camp near Narrowsburg, where I spent the happiest weeks of my young life—yet, I can’t agree with him. Fear is not the only thing we have to fear. There’s shame, for instance. Fear is of the moment; shame lasts. We can run from what we fear, but we carry the shame of running with us.

I was fourteen that fall, the tan of summer camp fading from my forearms, and back in the city, in the cramped railroad flat on the lower east side I shared with my parents and my younger brother Milt—Milt-the-stilt, as I was calling him then; he’d busted his leg sliding into home in the district championship game and was clumping around in a cast that made Mrs. Zuker, the seamstress in the apartment below, thump on the ceiling with her yardstick whenever he crossed the floor.

It had been a mild fall day, chill but bright under vaulted blue skies that offered no hint of the threat to come; now it was evening. A Sunday. I’d come in from my troop meeting and was finishing my civics homework at the kitchen table, still in uniform, while my mother put Milt to bed and my father poured the one scotch and soda he allowed himself each week and prepared to settle down to “The Chase and Sanborn Hour” on NBC. There remained some ritual to this, some formality—we’d only had the radio, a Truetone, for a year (prior to that we’d squeezed into the Zukers’ to listen to their set on special occasions like the inauguration in ’33), and no one ever spoke over it—so it still startled me to hear my father belly-laughing at Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy. The radio, I knew, had been bought for the news—that’s how my parents justified the expense ($19.95, from Cantor the Cabinet King on Radio Row—my father bequeathed me the nickel change for carrying it home from Cortlandt Street). The “situation in Europe,” as they called it, was worsening. And indeed, that month we’d listened gravely to the report of the Munich crisis, Germany’s entry to the Sudetenland interrupting The Hound of the Baskervilles, my mother bowing her head, my father murmuring darkly, “Didn’t I say so?” (There’s a comfort, I suppose, in our worst fears coming true—a sense of control amid the chaos; it’s what we can’t foresee that shocks most deeply.) Milty and I were allowed to listen to ball games—Milt still forbidden to touch the radio, while I handled the dial as gingerly as a safe-cracker listening to the tumblers in a lock—but it was understood that if my father needed to listen to something, no matter the score, no matter the inning, he could change the station. “You think the radio’s for what, boys? Fun only?” he asked. “A kind of insurance, is what it is.” (He was in insurance, himself, though, if he remembered he affected to call it assurance, after the British fashion). When I explained it to Milt, I told him that to Pop, the radio was like a guard dog. It would bark a warning if anything was happening in Europe.

But until then we had Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy. I’d pointed out to my father a ventriloquist act on radio was no great shakes, but he didn’t care.

Tonight Edgar was promising Charlie a ghost story.

BERGEN: Say, Charlie, do you like spooky tales?

CHARLIE: Sure! They scare me out of my wits. Still, it’s good to get out sometimes!

Sipping his scotch, my father repeated the punchline to himself, chuckling, but also in his careful way—his striving, immigrant way—rehearsing it in case he might be able to use the witticism himself at his office. He was an actuary back then, one of a team of calculators bent over their racketing adding machines, but he dreamed of being an agent—“to assure people, Edith, to calm their fears.”

Perhaps because he had no singing voice, Pop leaned forward to twist the dial when Nelson Eddy came on to do “Song of the Vagabonds.” “What, Saul,” my mother called from the doorway, giving a wiggle of her hips, “you got something against a little music?” but my father shushed her so sharply I looked up from my books. He was bent close to the radio, his eyes on us, but wide and unseeing. “We interrupt this broadcast.” It was the first bulletin.

Things moved fast after that. There was a banging on the floor below—Mrs. Z—and my father hurried down. By the time he’d run back up there were drumming feet overhead and in the halls, the din stilled only momentarily for a statement from the Secretary of the Interior. But where was the President? How I yearned for the calm “Good evening, friends” of one of his fireside chats.

“C’mon, already!” my father cried when he reappeared. “To the basement.” My mother ran to wake Milt and I followed her, looking around wildly for something to save. What was my most valuable possession? My magic apparatus, of course. I’d been given a set—trick deck, silk scarves, and my prize, an oboki box for coin tricks—for my Bar Mitzvah. I snatched the lot up, along with the reel of invisible thread, and stuffed it in my pockets. I could hear my mother trying to explain about the Martians to Milt. “The Martins?” he asked sleepily, scratching the toes that peeked out of the end of his cast. “Who are the Martins?” And then my father was there. “Forget Martians, Edith. Never mind that. These radio fellows don’t know bupkis. It’s Germans. See if it ain’t.” Until then I’d not been so afraid. I didn’t know anything about Martians. But Germans … I could see it in Milt’s saucer eyes … Germans were real. And that’s when it happened.

“What’s that?” my father broke off.

The warm, shameful load settled in the seat of my pants.

“What’s what?” my mother asked.

“Oi, that stink.” He looked at me, his nostrils bulging. “You smell it?”

I gave a sickly nod. The stool in my drawers nestled against my scrotum like a third testicle.

“Poison gas!” my father cried. “The radio said they was using poison gas. Quick, Mother, wet towels. To the basement everyone!”

He knelt to hoist Milt, while my mother snatched up towels, and I hurried ahead—not so swiftly as to disturb the pendulous weight in my pants, and not down the stairs, as my parents would assume when they came clattering into the hall, but up a flight to the communal bathroom.

I was that fourteen-year-old paradox—a bookish boy who read nothing but tales of derring-do. Scouting, with its rewards for studious outdoorsmanship, was a perfect fit for me. Milt was the family athlete, but behind my books and my glasses, behind and beneath my brains, in my heart and gut, I had always been sure I was the family hero. All through my father’s laments about the “situation in Europe” I realized, I’d felt unafraid. America, and by extension, I in my starched scout uniform, would rise to the challenge. Prove ourselves. My father carried that old European stain on him—that immigrant, Jewish fear—but I hadn’t been touched by it. I had pitied him rather—assurance, indeed! Who was he kidding?—or been ashamed for him, always confident in my own bravery, my own mettle. But now? The turds in my pants—one long, one short—made an exclamation mark of excreta. After wiping myself, after forcing my soiled drawers down the bowl, I didn’t want to live, didn’t want to face anyone I knew again. I’d disgraced my uniform. All I wanted to do was kill Martians, Germans, whoever—kill the enemy who’d so shamed me.

I had a pen knife in my sock drawer—my Boy Scout Barlow. I should have thought to stuff it in my pocket before I left the flat, but I went back for it now. Puny as it was, it also felt right somehow in my frenzy; a weapon for gouging and hacking, ripping and stabbing. The radio played on, eerily, to the empty room; beside it, my father’s scotch was as still as amber. My parents would be noticing my absence in the basement any moment and my father, for sure, would try to stop me. I grabbed up the knife from the bureau—the merit badges on my sleeve stiff as scales of armor—and hurried out, catching a report of the Martian machines crossing the Hudson. A commentator was describing their progress from the top of the CBS building, with a mix of dread and wonder, and as I listened his voice rose to a wail and then abruptly fell silent. I knew where that building was. If I wanted to find a Martian to kill that was where I would start.

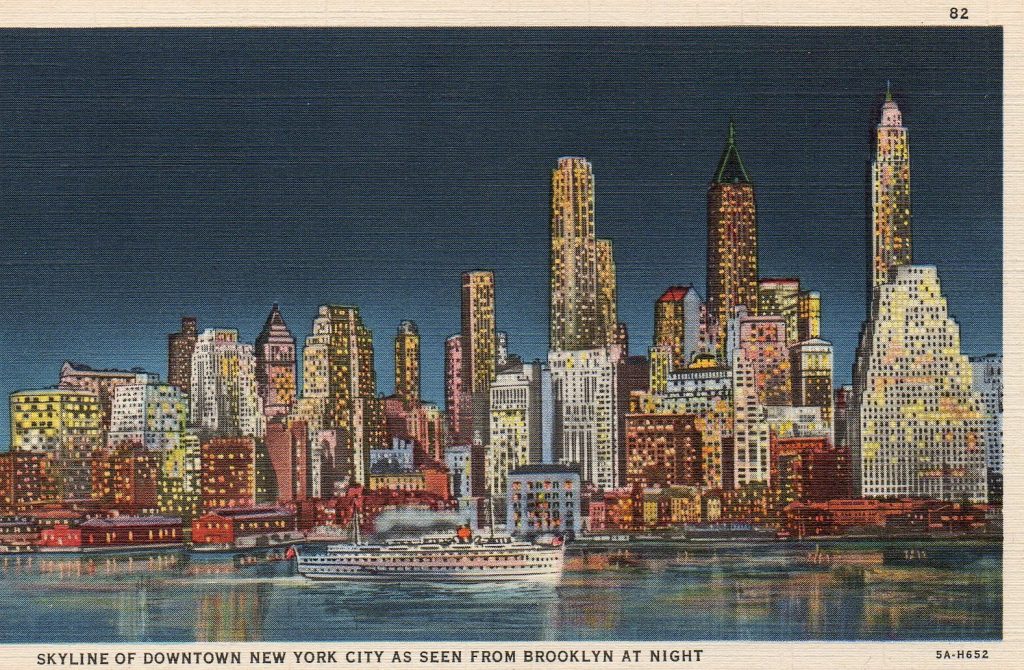

Houston Street was quiet as I sped along on my father’s Schwinn, the WPA playground on the corner deserted in the darkness, the jouncing of the bike on the cobbles the only sound. It was a Sunday night, but my first thought was that people had fled. I was looking up, in any event, trying to make out the meteor showers the radio had mentioned, though all I could see overhead were strands of washing swinging in the breeze, like ghostly flags.

On Bowery, the flophouse stoops were deserted, the sign outside the Tri-boro Barber School the only light, the red-white-and-blue spiral twisting upwards like smoke. I kept to the middle of the street, wary of the city’s canyon walls collapsing inwards, flinching at the silhouette of each water tower rising over the roof tops. As soon as I turned onto Broadway, though, the crowds began to grow. I expected panic, screams, but there was calm, normalcy. In Wanamaker’s still-lighted windows the manikins were posed in small domestic groups—walking to church, gathered around the phonograph, sitting down to dinner—and the people in the streets seemed no less oblivious. They hadn’t heard yet, and I felt a sickening nostalgia for such innocence. The scene was the same in Union Square. In the windows of Klein’s a family in new topcoats kicked through tissue paper leaves, while a boy set to carving a toothy pumpkin. A crowd of men in snap-brimmed hats was spilling into the intersection at East Fifteenth—I looked in vain for police, National Guard, among them—but when they’d passed all I saw behind them were theater signs promising “Glorified Follies.” I was enraged by their ignorance, but then, steadied by the rhythmic turning of the pedals, it began to dawn on me. Where were all the fires? The only smoke I could see were the wisps from steam vents.

The Flatiron Building was looming ahead and for just a second it looked like one of the Martian machines rising up before me. But then I was past it into Herald Square, Macy’s to my left, the flags on its roof glossy in their spotlights, the Sixth Avenue El howling overhead, and people everywhere, on foot, in cars, hurrying, but not running. I thought, at first, I must be dreaming. It seemed too good to be true. All these people still alive, the city, my city, still whole and happy. I flew down Broadway, my neckerchief fluttering behind me, racing the flickering marquee lights, oblivious to the honking of taxicabs, my arms outstretched, as if to stroke the incandescent bulbs lining the street on either side. I swear I could feel their warmth. When I got to Times Square it was so obviously vibrant, so bustlingly alive, the news zipper coursing like blood through the city’s veins, that for a moment I just stood there, one foot on the ground, the other on the pedal, gazing around at it, loving it really, and everyone in it. I wanted to pump every hand, slap every back, in the place. I felt so American suddenly, as if I’d never even realized my slight hesitancy before, my tiny reserve. My father told us once that when he landed at Ellis Island Lady Liberty was still copper colored—”She shone, boys!”—and now the whole city seemed to glow as if brand new. I was just about to turn for home, already looking forward to bursting in on them—my dear parents, little Milt, who I’d feared I’d never see again—with the joyous tidings. And then, out of the corner of my eye, I caught the bright line of news, lit up and racing around the buildings, through the signs for Tip Top Razor Blades and Gold Stripe Stockings. “…. Terrorizes Nation,” I made out, and then a moment later the banner angled back around: “Orson Welles Broadcast Terrorizes Nation.”

A chill autumnal air stole up the legs of my shorts.

People around me were already talking about it, and as they talked I felt I could hear behind the words their laughter, bubbling away, pulling at the corners of their mouths. Because these people hadn’t been made fools of the way I had, the way my father and mother and brother had been made fools of, the way our neighbors had been made fools of—all those foolish Jews, huddled even now in their basements, even here in America, the real aliens.

Within moments of wanting to shake every hand in Times Square I found myself slinking away, fearful of being caught in those bright lights, singled out: “the boy who fell for it.” For falling is what it felt like, a hollowing descent, each second worse than the last. I’d not only proved myself a shameful coward, a baby with no control of his own bowels, but a fool to boot. Yellow and stupid. But then, as before, anger rallied me. I’d wanted to kill Martians, Germans, the enemy, and I still wanted to kill, only now it was the liars, the hoaxers, the radio charlatans.

I knew of this Welles—Broadway sensation, and rising radio star, he was it back then. My father had a subscription to Time, and Welles had been on the cover the year before. Inside, he was called the Marvelous Boy, a prodigy, exactly the kind of example my father was inclined to point out to me. I’d felt a little thrill. What would it be like to be called a Marvelous Boy? To be called it, not only by one’s parents, one’s aunts and uncles (I was already the apple of the family eye) but by the press, by the nation. Welles was a magician himself. For a while I even styled my family magic act The Marvelous Boy. And now here was my idol tricking me, reasserting his own marvelousness—for surely it was a kind of marvel, this hoax—at my expense, proving my lack, my utter want of marvelousness.

I’d been heading for the CBS building when I thought I was after Martians, and I continued there now in search of Welles, pedaling furiously, running lights and once swerving around a florid-faced man in an intersection who only blocks later I realized was weeping.

There were police cars outside the building and a crowd, small but swelling, as I stared from the other side of the street. Several of the men were bareheaded, as if a strong wind had just whipped by. When I approached I could hear voices assailing the cops. “You better be here to arrest those rotten bums! It shouldn’t be allowed what they done.” Another fellow, raised up on the running board of a parked car, was hollering questions: “Officer, officer? Is Mr. Welles still in there?” It was a newspaperman, his press card tucked into his hatband like a feather. The cop he was addressing, a burly specimen so tightly buttoned into his uniform he looked like he was about to burst, just glared at him. “Would you still be here if he’d left?’ the reporter asked and the cop looked away over the heads. “Fat chance!” the crowd brayed. “Settle down,” gnashed another brightly buttoned cop, but the newsman persisted. “What about the rumors of a bomb? Is that why you’re here? Have CBS and Mr. Welles been threatened?” A throaty cheer rose from the throng at that. Only the sound of smashed glass—a flash bulb—quieted them for a moment, men ducking as if for cover, before the clamor redoubled.

There must be a back door. In search of it, I went, but all I could find was a shuttered loading dock, an ambulance idling nearby in the alley. “Has someone been hurt?” The driver shrugged under his white coat— “Not yet!”—and went back to his Journal-American. And then it occurred to me. The whole crowd was full of people who’d been taken in. They were my people, but I didn’t want to be one of them. I ran around the front of the building again and pushed myself into the crowd beside the reporter, pulled at his arm.

“Hey, Mister!”

He looked around and down. “Whaddaya want, kid?”

“They’re coming out the back. The cops and radio types. There’s a paddy wagon and a couple of cabs just pulled up.”

I’d said it loud enough for others around us to hear and before the reporter could respond, the word was already rippling through the crowd—beaming out, as I pictured it, in concentric waves. Bleep, bleep, blip. “Welles is getting away. He’s making a run for it. Round the back!”

And then they were gone, with the cops in pursuit, their nightsticks clacking, and even the liveried doorman coming out on the sidewalk to catch the show. I almost slammed into another cop by the elevators, but the stairs were unguarded and I ducked up them, pausing at the top of the first flight to listen. I was elated, swollen hearted, until sobered by the thought I’d just done what Welles had done, fooled everyone for my own purposes.

I couldn’t risk being seen by the elevator operator so I began the long climb upwards. The directory listed CBS studios on the twentieth floor and I hated that louse Welles more with every echoing step. The ferocity of my anger made me more breathless than the climb.

I figured a cop might be stationed at the top, but when I cracked the stairwell door the corridor was empty. Somewhere a phone was ringing, then two, then three but I waited and waited and no one answered. Finally, I slipped down the passage, knife open now, the stag handle growing warm and slick in my fist. At the end of the hall was a plate glass window and approaching, I could see a studio beyond: microphones on stands, seats for the orchestra, splayed scripts and cigarettes still burning in ashtrays. A couple of jackets were draped on the back of chairs, but there wasn’t a soul in evidence. A gauze of smoke hung from the tile ceiling. The only thing moving were the trembling needles on a row of gauges. The rats had already beat it, probably while I was on the stairs, my own low hoax coming true before my eyes. But then I heard voices.

“No, sir. Enough is a sufficiency! Unhand me.”

A door was opening down the hall.

“I will not, I say I cannot, relieve myself in the ladies’ room. Bad enough that we should have to hide there.”

A thin cloud of blue smoke drifted into the hall, and then out strode … Welles himself. His back was to me—he was in shirtsleeves and a vest, beneath which I could make out the ‘Y’ of his suspenders—but I caught his profile as he shouldered the door to the next room and vanished.

I should have followed him—the men’s room was the perfect setting for a poetic revenge—but I froze, suddenly terrified of getting cornered in the bathroom, and so I was waiting for him, knife in hand, when he emerged.

He gave a weary double take: “What have we here?”

“I’ll stick you if you call out,” I managed to growl in my best Dead End Kids.

“My dear boy!” He tilted his head and smiled with a kind of relish. I could already hear him telling the story: A Boy Scout! With a pocketknife, no less! His breath smelled strangely like the ship-in-a-bottle I had at home. Like glue, I thought stupidly, before I figured he’d been drinking.

I gestured for him to move, and he held up his hands and mouthed, “Whoa” but backed up nonetheless with a little skip in his shuffle. No one can see you, I wanted to bark, stop acting, but then it came to me that these little theatrical flourishes were for my benefit, that I was getting a private performance, and I was oddly flattered.

I pressed him back into a dark office—the phone on the desk started jangling which made me jump, but Welles just leaned over, lifted the receiver an inch and dropped it again—and then through a pair of French doors out onto a stone balcony. I could picture the doomed newsman from the broadcast perched right here, and for a dizzying moment I felt the jolting shock of his death again.

“One day all this will be yours,” Welles murmured, throwing open his arms as if to embrace the skyline. His brilliantined crown glinted in the gloom; one glossy lock had slipped free, curling round to join his eyebrow like a horn, and when he combed it back his hair shone like a new 78. “Well, I trust you’re a critic, young man, a budding one at least. But has no one told you that the pen is mightier than the … pen knife?”

He stared at me frankly, dipping his head as if to listen. Once in a school play I’d seen someone do this when one of the other actors had forgotten their lines. Welles had the same look of expectant impatience, but this time there was no one at the footlights to hiss a prompt.

“Why did you do it?” I wailed at last. A huge grin spread across his cheeks as if he were about to spit in my face with laughter.

“Garbo talks!” He pulled a cigarette case from his pocket, put one in his mouth. “Would you care … ? No, of course not.” The case snapped shut, a vast golden wink. “Where was I? Oh yes. Why? Why indeed?” He struck a light on the stone balustrade, fired up, and tossed the match still aglow over the side. For a moment, I expected the whole city to go up in flames. “I could give you the critical explanation. You know how the original—the novel, by my namesake—ends on such an odd flat note. Do you know it?” And actually I did, it came to me; I’d read it the summer before on the bleachers above Milt’s batting practice. The War of the Worlds, of course.

“You recall then how it ends. The great Martian enemy, unstoppable, all-powerful, felled, not by might or man, but by disease, the common cold. By accident, if you will. Yes, you recall? And how did that make you feel?” He stuck his chin out, his full, firm jaw jutting.

“Didn’t much like it,” I muttered.

“Quite so. Very astute. Me neither! It lacks—ten-cent word—catharsis. Mankind saved, yes, from this terrible evil, yes, but not through his own efforts. Unsatisfying, by god! And yet, we were stuck with it, and so we made it the point, so to speak. Made of the piece with the trick ending, one long trick. And here we are at the punch line. You should be happy, no? The end of the world averted. Humanity saved.” He studied me. “But you’re disappointed, aren’t you? Underwhelmed. It’s an awful anticlimax—peace.”

“I wanted to fight,” I choked out. “I would have.”

“Spoiling for it, were you?”

“Yes,” I groaned.

“So desperate you’d have fought anyone, even Martians, so long as someone told you to.”

“If they were the enemy, yes!” I felt myself close to tears and Welles, in a moment of discretion or disgust, turned away.

“Oh, quit being melodramatic.”

He was leaning over the parapet, gazing out over the city, like a king in his castle. His back was to me and I could have stabbed him then and he knew it. My hand slowly sank to my side.

“It’s so quiet,” I said dismally, and he nodded.

“That’s why the studios are up here, above all the traffic noise. My!” He whistled softly. “Would you look at all those dots down there? Poor devils.” His face was a broad, round moon and I remembered that Welles had been described as just that in Time, a new moon rising over Broadway.

When I looked over the edge, I expected the city to be still, but down below the streets were blazing, Rockefeller Plaza glowing like Ebbets Field for a night game. Shiny yellow cabs slid down the avenues like pats of butter on a bright blade.

“Impressed?” he asked and I nodded. I’d never been so high, never seen the city from above.

“Always reminds me of the theater,” Welles was saying. “If you climb up to the flies and look down. It’s magical at night, but in the morning sometimes, early, when there’s no traffic, and the light is flat, the buildings look like so many boxes and crates, piled up.”

He flicked his cigarette out into the darkness and I watched it fall toward the spines of St Patrick’s. I felt my glasses lift off my nose, swing pendulously from my ears, and I jerked back from the edge.

“You shouldn’t frighten people like that,” I told him softly.

“Quite so.” He glanced at the knife in my hand.

“Oh, this was just to get you to listen.”

“Quite so,” he repeated dryly.

“And to talk,” I added.

He sighed, took out another cigarette and tapped it on the case like a gavel. “OK, son. Here it is. The lesson, the message, if you want to get all Brechtian about it. Maybe fear isn’t so bad. Maybe people should be frightened every so often. It’s a survival mechanism, if you think about it properly. Fear’s how we see the future—it’s no accident that the best science fiction is cataclysmic—a very particular future at that, one without us. So we run, we hide, we try to survive. Nothing wrong with that. We wouldn’t be here if our ancestors hadn’t been frightened.” I thought, at once, of my father and Welles must have seen a shadow wing across my face. “That’s right! Not the home of the brave, the home of the afraid. Heroes are as much of a hoax as anything you’ve heard tonight.” This was the man—suddenly, I knew the voice—who’d played the Shadow for a year, and yet oddly that just made him sound more persuasive.

He hunched over his cigarette to light it. “So now what?”

“You could at least apologize.”

“For scaring the pants off you?” I colored at the reference. “For playing such a dirty trick? It is Halloween. Be reasonable.”

Trick-or-treating was catching on at the time; my father, when he heard of it, dismissed it as “begging,” but I felt this Welles owed me something. I did still have the knife, though when I brandished it now it felt like a rubber prop, part of a crummy costume.

“How about a real trick, at least?” I asked shyly. “You’re a magician.”

He blew a stream of smoke into the night sky. “Do I detect a fellow aficionado of the dark arts?”

“Maybe.”

“And what would you like? I don’t see a lady to saw in half and I’ve already made Martians appear and disappear tonight.” He mimed cutting a deck of cards, as if to say, Is this your fear?

“How about a levitation?” I’d been trying to master the skill for weeks now. “I have some thread.”

“Please.” He rubbed out his cigarette against the stonework. “We don’t speak of ‘how’.”

“Oh, of course.”

He shot his cuffs, looked around for a moment. “Well, let’s see. Levitation? Ah!” He bent and from a little eddy, swept up against the wall, produced: a leaf, a golden maple. He opened his fist and there it was, slightly curled on his palm; strange to see, blown so far above any tree tops.

“To suspend this leaf,” he hissed in a stagey aside. “I beg you to suspend your disbelief.”

I nodded solemnly.

“Very well then. We will endeavor to reverse the laws of nature,” he declaimed. “To make rise that whose time it is to fall.” And as I watched, slowly, ever so slowly, the leaf wafted off his palm, his other hand seeming to draw it, coaxing, into space.

“Bravo!” I whispered. He glanced at me from under his brows, furrowed as if with concentration, to see if I was sincere, but I was. It didn’t matter that I knew how it was done.

“Ah, but it’s an effort to defy nature!” he groaned, opening his arms abruptly, and releasing the leaf. A breeze tumbled it over the parapet, and I watched it twirl away until it vanished against the gleam of Madison.

It was a beautiful view, I saw—the Empire State to one side, the Chrysler building to the other, the night sky seeming to rest on their pinnacles, and between them down the long lighted river of cars, I thought I could just make out the cluster of spires at the tip of the island, the New York World building, the Tribune building, and looming above them the Singer Tower, its great lantern burning steadily. Those might be dots down there, but they’d raised those towers, built the very heights from which we looked down on them.

Beside me, Welles stepped back, rubbed his hands as if washing them, the classic magician’s gesture of acquitment.

“How could you imagine it,” I breathed, turning back to him. “How could you imagine it all gone?”

I can still see him, drawing himself up. “Genius!” He gave the smirk of a baby-faced bully. “Scout’s honor! No, but really, how could you believe it? Call me a fraud, if you like,”—a little bow—“but who would have thought the country so full of mugs and suckers.”

For a second, so sneering was his tone, I thought he’d said Zukers. His bow had brought his face close, and I backed up against the balustrade. I could feel his spit, his breath upon me, blowing on the embers of my anger, and instinctively I brought the knife up again. Just to scare him, I swear.

“If you’re so brave,” I jeered, “what were you doing in the ladies’ room?”

His face clouded at that, brows massing stormily, and he lunged for the blade, a hero after all. I had to step aside smartly—a sudden terror of sticking him—and in that moment, he was gone. Like a magic trick. Poof! It took me a long second even to figure it out. He must have been too stunned himself to cry out—no dying words—though if he had perhaps all he’d have said was allakhazam! By the time I looked over the edge he was already a dwindling speck, limbs gently flailing like a runner.

The papers the next day called it a remorseful suicide—the only real fatality of that night of terror, despite all the stories of heart attacks and suicide pacts. Louella Parsons compared him to Icarus. “He, who made a nation fall for his hoax, ” Walter Winchell intoned, “fell for it himself, finally.” It was just the ending people needed really, the very catharsis Welles had talked of (right down to the fact that he was carried off, and officially pronounced, in the waiting ambulance I’d seen earlier—an apparent coincidence that was actually a savage irony: Welles, it came out later, was in the habit of racing from the radio studio to rehearsals for a new play by means of a rented ambulance). He could be forgiven and even grudgingly admired now that he was gone.

At least by some.

“Liars never prosper,” my father observed with grim satisfaction, though even as he said it I knew it wasn’t always so. No one, after all, mentioned me in any of the papers. I was gone by the time the reporters showed up, down the stairs, out the back. Scot free—apart from the hell my father gave me for my disappearing act.

Yet, I’ve never stopped thinking about Welles (even now when he’s no more than a historical footnote) and not just at Halloween when his cautionary tale is dusted off, or on the infamous day of Pearl Harbor when for a second I thought—hoped against hope—that that was a hoax. I’ve thought of Welles every time I didn’t want to believe something—most recently when all around me, my fellow citizens seem duped and beguiled by fear, which we fall for almost as a lover—and wondered for a second, Is it him? As if he’d lived on somehow.

What would he have done if he had? (The broadcast might have been the end of his career, but also perhaps the making of it.) What would I have done, for that matter? Not given up my scout’s uniform that fall, probably. Certainly not refused my country’s four years later. Perhaps even pursued the magic act I abandoned immediately after that Halloween—at least until ’42 when I contrived to make my father’s pride in me disappear overnight, or ’45 when poor Milty (my hero as I was his coward) vanished in a white puff of antiaircraft fire conjured by me as surely as if I’d pulled the trigger.

My father lost his reverence for radio that night—afterward he listened to it in his undershirt, talked back to it—I lost my faith in everything else.

But, of course, you’ll say, it didn’t happen like that—not the part about Welles’s death, at any rate, however fervently I might have wished myself revenged on him. In the end, it doesn’t much matter. It turns out it’s not enough to expose a lie, punish a liar. A big enough lie outlives its liar; it lives on in our shame at being duped—at least until, like dear Milton, we die ourselves.

And even if it had happened just so, who would believe my confession? Who needs another twist in the tale? Who wants to be tricked again? Fool me once, shame on you, my father used to say; some old saw picked up around his insurance office. Fool me twice, shame on me.

That evening, after his little sleight of hand, Welles and I stared out over the city for a few moments more until we heard someone calling him from inside.

“Orson! Orson, goddammit, where are you?”

I must have blanched, but he told me not to worry. “I reckon I’m in more trouble than you, tonight.” He laid a hand on my shoulder. “Just wait here until it’s quiet.”

At the door to the office he gestured one last time at the view, as if bequeathing it to me.

“‘High growth of iron,” he recited, “splendidly uprising towards clear skies.'”

“Whitman?”

Welles gave me a close look. “Earned your poetry badge, I see.” He nodded at the Empire State, shouldering above the city. “You know they built that mast on top for airships to dock? Never happened, and won’t ever happen now, of course, since Hindenburg, but wouldn’t it have been grand to see one of those huge ships glide in over the city, hang there alongside her?”

I stood there, for a long time after he was gone, gazing at that silvery turret—still beautiful, but made obsolete by disaster—picturing King Kong raging from the same peak, swatting at biplanes (I’d seen the movie with Milt that summer, his hand clutching mine in his tight knuckle-baller’s grip). It seemed, then, as if only monsters and Martians could destroy the city.