Who hasn’t noticed the rhetoric we use for a life-changing event? Where-we-were or what-we were doing—when. For example, 9/11: I was in my bedroom lacing my sneakers for a run; I was stepping out of the shower when my sister called; I was in my car and I knocked my coffee onto my lap.

Kind of PTSD talk? I asked my son, a therapist. And why was it so ubiquitous?

It’s a known phenomenon, he said. Psychologists have a name for it: A flashbulb memory.

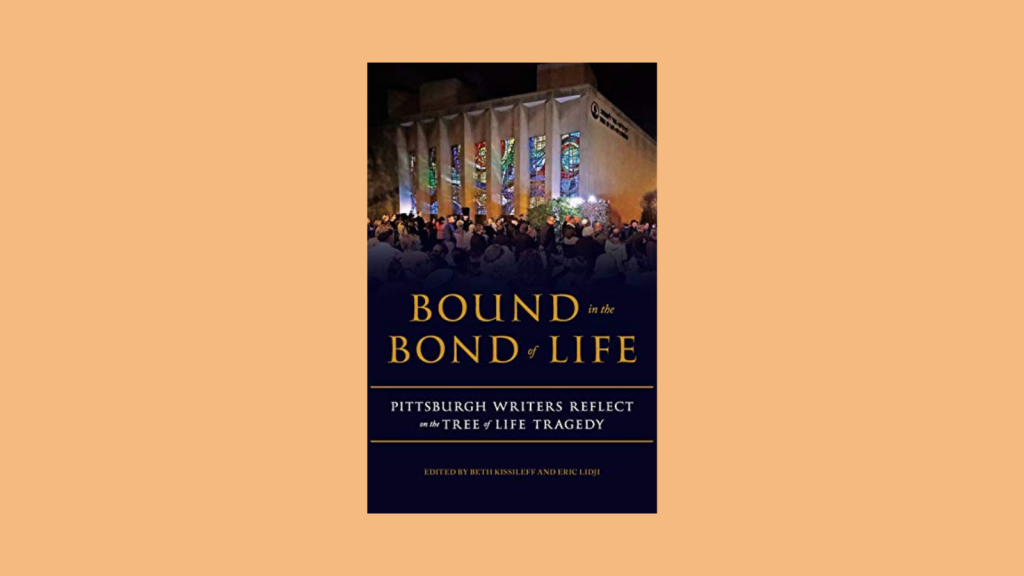

And so, with the flashbulb, begin many of the essays in Bound in the Bond of Life, Pittsburgh Writers Reflect on the Tree of Life Tragedy; where the writers were and what they were doing, the memories at first deceptively calm, and then in the aggregate nothing less than fierce. The collection is masterfully edited by Eric Lidji, writer and professional archivist, and Beth Kissileff, writer and and scholar, as well as the wife of the rabbi who, during the massacre, hid with his congregants in a storage room in the Tree of Life synagogue.

In this collection of essays a reader shouldn’t expect, Kissileff cautions, “… the comfort of relentlessly cheering narratives… full of inspiration and confidence.” As much as this group of 24 writers try, would it ever be possible to smoke out meaning and power from devastation and loss? For the editors, whose task was to wrest the responses into sense and order, their job was a feat in and of itself. Contributor David Shribman was the lead of the three journalists in the collection who won the Pulitzer Prize for coverage of the event. He categorizes the sections into three emotional beats: How the community learned of the event, how they have processed and grieved, how they have carried on.

The Tree of Life massacre took place in the Squirrel Hill neighborhood of Pittsburgh. To label the neighborhood All American Tranquil would be accurate. In fact, as opposed to metaphor, Squirrel Hill was Mr. Roger’s neighborhood, charmingly described in one especially crisp essay, by New York Times correspondent and Pittsburgh resident Campbell Robertson. That day was a typical October Saturday with “Halloween pumpkins mugging on front porches.” Squirrel Hill is a sanctuary for old-timers who nevertheless welcome the newcomers with open arms. In a few generations, if the newcomers are lucky enough, they’ll be old-timers, too.

A reader might be impatient for the facts and timeline of the massacre which the essays, as read in sequence, reveal gradually and chaotically, in an eerie mimesis of the way the locals experienced the events in real-time. Sabbath observers heard the rumble of police cars and because their phones and TVs were turned off had no access to media and so locked their doors and anxiously speculated. Reporters called to the scene were restrained behind police lines. Families eating their breakfast cereal or out walking their dogs heard the screech of the sirens. What could be going on in that place? In that time? Every one of these talented writers is brave enough to be transparent about their struggle to find—or not find—the right point of physical and emotional, and professional observation.

Here are the facts of the day: At 9:45 am, on Shabbat: (Saturday), October 27, 2018, a lone suspect approached a synagogue building called the Tree of Life. Wielding an assault rifle and several handguns and shouting anti-Semitic slurs, he entered the building and began to fire. Three different groups were gathered in the building on that Shabbat: two in congregational prayer sessions located in the chapel and the basement, and one group was gathered near the front door for a bible study session. Six people were injured in the attack, including four police officers. The death toll was larger: eleven men and women, ages 54-97. Among their survivors were spouses and dozens of children, grandchildren, siblings, and hundreds of coworkers, patients, co congregants, and friends. First responders arrested the shooter at the scene. He has since plead ‘not guilty’. It has been revealed that he targeted the building’s services particularly because it hosted a ‘refugee Shabbat’ the week before. The killer could not “sit by” and watch his (American) people “get slaughtered” by invaders.

The massacre is considered the largest ever terror act against Jews on American soil. But it is not a book created only for students of Jewish history. The imperative to a general readership calls to mind James Joyce’s quote: that in the particular is the universal. Award-winning contributor Tony Norman echoes the idea. Norman is an African American newspaper columnist in Pittsburgh who is “well acquainted with hate” and racial invective. He lists out the hate-motivated shootings in and near Pittsburgh, as well as other recent tragedies of hate and gun violence such as the Charleston church in 2015 and the Route 91 Harvest Music festival in Las Vegas, 2017. Norman writes of the “feeling of impotence” as one hears of the latest massacre tragedy, but importantly suggests that the exercise of organizing and writing the experience has transcendental value . “Each spasmodic act of violence has its own unique cultural signature that is initially baffling until we impose order on the tragedy once the terror passes.”

Several of the essays catalog, in great detail, often with photos, community response which included vigils, services, and prayers from every sector of society and religion, from within Pittsburgh and without. Sidewalk memorials included handwritten signs with messages of love and togetherness, crosses with Jewish stars on top, glass and china flowers, natural flowers, posters, metal angels, tea lights. Perhaps the dream of a diverse and inclusive America is alive and well. Lidji’s essay on the process of creating an archive from the the sidewalk memorials and memorial artifacts translates the physical process into an emotional process. (The idea is further developed in an interview with Lidji in an Atlantic Magazine article). Another essay takes a close look at the Jewish practices of death, burial and mourning, including an explication of the 13th-century Aramaic memorial prayer, the Kaddish, which oddly contains no mention of death.

.

The editors include the Shabbat drasha (sermon) of Rabbi Daniel Yolkut, leader of a local orthodox congregation who spoke the week after and on the year anniversary of the event. Rather than watering down the drasha and translating the Hebrew and insider vernacular, the editors made the bold decision to present the drasha as spoken, inserting footnotes and emendations for the general reader. Yolkut connects that week’s Haftorah, the secondary Torah reading on a Shabbat or holiday, to the massacre. Elisha, the prophet, responded to an impoverished widow’s pleas for sustenance . He filled her vessels with oil and asked that she borrow whatever jugs and jars she could from her neighbors. She was thus saved from poverty . On the point of borrowing from neighbors, Yolkut expounds on the constant flow of divine blessing that can be accessed in this world, but also emphasizes the need for vessels to contain and experience it. On the metaphorical level, the vessels include kindness—which he does not interpolate as so many do as tikkun olom, i.e., social justice. He’s referring to the the other kind, as in the kindness of community members and strangers of every race, type of identity and religion, from all places in the world, who have offered comfort. He also includes the particular kindness called kavod ha meis, the concept that the body has been a holy vessel for a holy soul. For anyone who has seen the pictures of the yellow-vested first responders climbing the scene of a terror attack in Israel this will now make sense. They are collecting all blood and body parts (which might include carpet, wood, cloth, and metal embedded with human matter) to take them to burial.

The final group of essays gives voice to the whisper that has run through the book. This event was the largest antisemitic incident on American soil. So what now? Are the floodgates open? Is this the place where experience and memory become the stuff of Jewish history? Will it fan the flames of the chronic existential threat that is Jewish history?

Essayist Barbara Burstin teaches courses on the Holocaust and American Jewish History at Carnegie Mellon and the University of Pittsburgh. She points out that in Israel, after a terror attack, the very place is cleaned up and restored to purpose in order to signal the victory of resilience. The Tree of Life Synagogue is boarded up; it will become a museum. What haunts Burstin, besides the Holocaust, is the Jewish history that preceded the Holocaust, the cycle of the historically fragile rise and fall of Jewish life in host communities. Whether by government injunction, mob violence, church mandate or a single person rampage; whether the hate comes from the left or the right, it has come. Whether by stake burnings in Toledo in 638, massacres in Rouen, Limoges, and Rome in 1012, a massacre in Lorraine in 1095, a pogrom in Kiev 1100, live burnings in Strasbourg 1308, mass slaughter in Prague in 1138 . These are just a few incidents from the seven-page single-spaced list of massacres and expulsions I have in front of me. Every one of these host communities entertained a golden period of Jewish residence and contribution to society. Can gun control laws and vigilance on hate rhetoric stop the flow of history?

Whew, enough! In the Afterword, editor Kissileff sums up the endeavor of the book: “Can one heal after gun violence? Can any of us feel safe again?…Perhaps for those reading, there will be an impetus to think about…and ameliorate the twin problems of antisemitism and gun violence…as well as the fear of the immigrant that is said to have propelled the shooter.” To that end, I would add that this is would be a book for high school and college curriculum.