There was something in Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Some syrupy sweet left too long to fester or historical blood pudding gone sour by the sound of Topsy’s screaming, finally made the peculiar institution unpalatable early in 1852 upon that book’s publication. And what could no longer be digested in good taste in the privacy of northern dining rooms had to be stripped from the table, uprooted from southern fields and parlors.

But well before Stowe’s passion play of plantation life, hundreds of first-hand accounts from the enslaved in their own words were printed in pamphlet, essay, and book form. Many of the more than 6,000 slave narratives published between 1703 and 1944 were as-told-by testimonials used in abolitionist efforts to make more personal and therefore more urgent to white audiences the Black experience of being captured, sold, stripped of all agency and held in bondage on American soil. `

A common feature of such work is a strong declaration of self, a moment of reclamation at the center of the narrative. He was “No Rogue, no Rascal, no Thief,” proclaims Adam on his own behalf in Adam Negro’s Tryall. Promised freedom at the end of seven years’ servitude to John Saffin of Massachusetts, Adam’s words and posture were published as a part of court record in 1703, when Saffin reneged on the grounds that Adam “behaved him self [sic] Turbulently, Neglegently, Insolently and Outragiously [sic].”

“I would ten thousand times rather that my children should be half-starved paupers of Ireland,” says Harriet Jacobs in her 1861 memoir, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, “than to be the most pampered among the slaves of America.” Such utterances of existential insurgency could get you killed in this nation’s 17th, 18th, 19th, 20th and 21st-centuries.

Such was the case the summer after the Civil War, when three years after the Emancipation Proclamation, the eleven-year-old daughter of a once enslaved woman still living on the Neeley plantation in North Carolina, turned down extra work at the end of a hard day. The former mistress threatened to withhold food, threatened a beating, and detained the child. When the child uttered, “No, you won’t whip me,” Mistress Temperance, in her fury, loaded a pistol and shot and killed the girl’s mother, coming around to block the path as mother and daughter attempted to walk away. That declaration of agency, the audacious-exploration of self and the actuated possibilities unleashed by an “I” or “we,” a “no” or “me,” are dangerous keys for the Black-bodied, capable of prying open that long-feared portal to an awareness by which we free ourselves and others in the face of savagery.

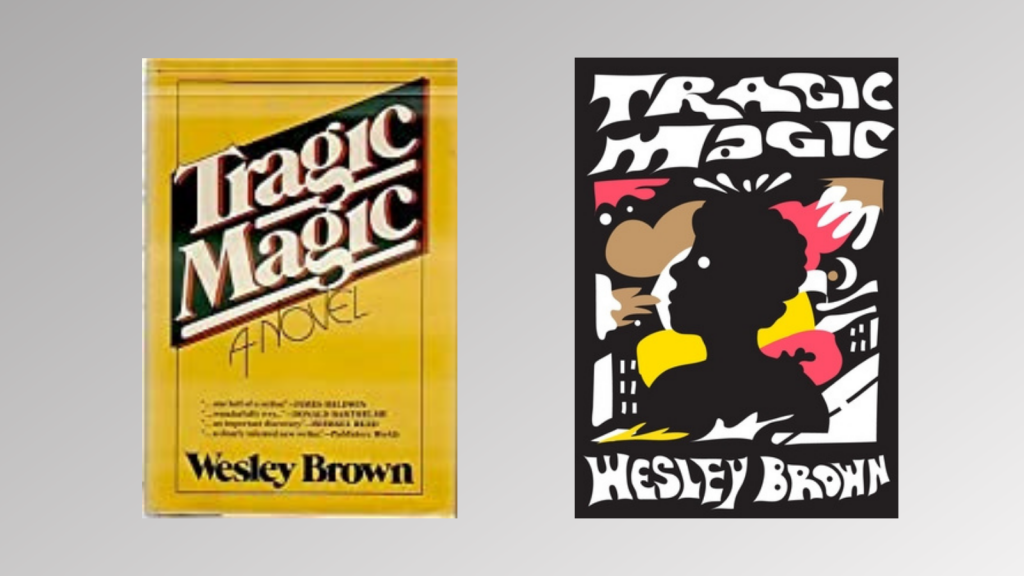

In many ways Wesley Brown’s Tragic Magic fits the criteria of the slave narrative. Set in a 1970s Harlem teeming with a revolution’s proselytizers and prophets, hustlers and lost lovers, protagonist Melvin Ellington finds himself freed after serving three years of a five-year sentence for refusing the draft, only to discover he remains chained to the hall of funhouse mirrors that is the Black American experience.

At the end of his first twenty-four hours among the rhythms of home that frame the novel, Ellington finds himself confined once again, laid out on what just might be his deathbed. His aptly named physician, Dr. Blue, asks the young flaneur, why he’d claimed the conscientious objector status that led to his imprisonment. Ellington starts and stops before landing on the truth that’s simplest. “I guess I just didn’t understand how the army had a right to decide when I should put my life on the line.”

Ellington’s sentiment was one many of us would share nearly fifty years later, after a certain election pressed us into unwilling allegiance to an administration that very openly promised it would lead us all backward. It was 2016, in the aftermath of this election, that the president of McSweeney’s and I began to talk about re-releasing classic Black works under the series title Of the Diaspora. There was a sense of emergency, but still enough room for me to breathe, as I stood in the Goya aisle of a neighborhood grocery, cellphone to ear, riffing with a friend about our shared love of works that say something, and the dream of honoring them. We saw the project as a celebration, reminder, invitation. There were works and writers from Wesley Brown to Paule Marshall, David Bradley to John Edgar Wideman, Sherley Anne Williams to Thulani Davis whose voices are incantations, binding lives in the Diaspora with the resurrecting power of everyday truths and ancestor-memory.

Am I permitted to say that right before news broke of George Floyd’s murder, I was enjoying conversation with Wesley Brown across the miles. It was Memorial Day. I envisioned him at his desk in Massachusetts, while I sat on my patio in Las Vegas sipping tea. Falling into the soft music of good company, we were talking the ways of white folk, white structures, White Houses and their overall dispositions and tendencies. “We’re living through that kind of reaction that’s been unleashed at specific points,” Brown said as we commiserated over lost moments of national majesty. “Every assertion of white supremacy in this country, where it becomes unleashed in the most violent ways, has come whenever Black people have made assertions for our right to live and to gain, and acquire, the means to live as human beings.”

Not even an hour after we’ve said our goodbyes—excited about the series and pledging soon to talk again—I walk into the family-room where my two sons and my aging parents stand as heartbroken witness to yet another lynching by police action on CNN.

In re-mapping the space between what was, what could have been, and the 4,000-mile stretch of the Atlantic that comprises the Middle Passage, poet-essayist Dionne Brand in her book, “A Map to the Door of No Return,” takes up the philosophy of a kind of meta-navigation posited by cartographer-theorist David Turnbull. Brand hips us to Turnbull’s insistence that the human psyche moves beyond geographic coordinates, that we make our way forward informed by a kind of epigenetic sonar, the kind of way-finding that precedes and surpasses wind rose or compass. Turnbull insists there is a cognitive schema—an internal map of a psyche, and of a people, shaped by what was, and possibly filling in what we are then capable of seeing on the path forward. With this in mind, Brand wonders if the cognitive schema for our people has been, and forever will be, captivity.

If slave narratives were an attempt to reassert a stolen humanity, to track-back, Wesley Brown’s Ellington willfully charts a path for himself, using what was stolen to re-orient as Coltrane, as Miles, as Vaughn intended — with jazz as our azimuth. “As an intern in the reed section of sound I have been bucking to win the critic’s poll as a talent deserving wider recognition,” says Melvin Ellington, newly freed and just beginning to unravel three hundred-fifty years of systemized navigation. “I know all the standards and am particularly adept at playing it as it was written, and flirt with the tragic magic in If, Maybe, Suppose, and Perhaps.”

In 1978, the year Tragic Magic is originally ushered into print by dynamic Random House editor Toni Morrison, Jimmy Carter is president; Muhammed Ali is the first heavy weight to win the title three times; Shirley Chisolm speaks at Vassar’s commencement; George Clinton’s band Funkadelic vows to show us how to “dance our way out of our constrictions,” and Arthur Miller, a Black entrepreneur in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, dies by “fatal force to the larynx by forearm or police stick.”

Weeks go by after our Memorial Day 2020. I wait a bit before touching base with Brown, again. In the meantime, Minneapolis is ablaze. Instagram and Facebook posts point out demonic figures frolicking in the flames.

The names of Breonna Taylor, Rayshard Brooks and Elijah McClain emerge, phoenix-winged. In Los Angeles, police fire rubber bullets into peaceful gatherings. In Philadelphia an officer aims for the head of a young woman who is protesting, smashing her teeth in. A police SUV plows through a crowd of lawful protestors in Brooklyn; in Fort Lauderdale a Black woman kneeling in surrender is attacked by police and slammed to concrete. In Buffalo, officers shove a 75-year-old white man and march over him as he lies bleeding. In Atlanta, Spelman and Morehouse students Taniyah Pilgrim and Messiah Young are pulled over while trying to make their way home before curfew. Atlanta P.D. tase the girl first, before yanking them both from their vehicle.

“You know, back in the day when people in the Movement would sit around and talk, we would see all these things,” says Wesley Brown, his patter like his art, naturally syncopated, a tune you want to follow. “And we would end our time together just shaking our heads, trying to find the lighter note, leave each other in good spirits. And I would say, ‘Well, it could be worse.’ And you know,” he says, his breathy chortle divining the hurt, our shared grief a heavily-trodden shortcut, “out of all the things one likes to be right about, this is the one thing I could do without.”

Follow this link to read an interview with Wesley Brown.

Visit our purchase page to order a copy of our Fall 2020 Issue, featuring an excerpt from Tragic Magic. You can read a preview of that excerpt here.