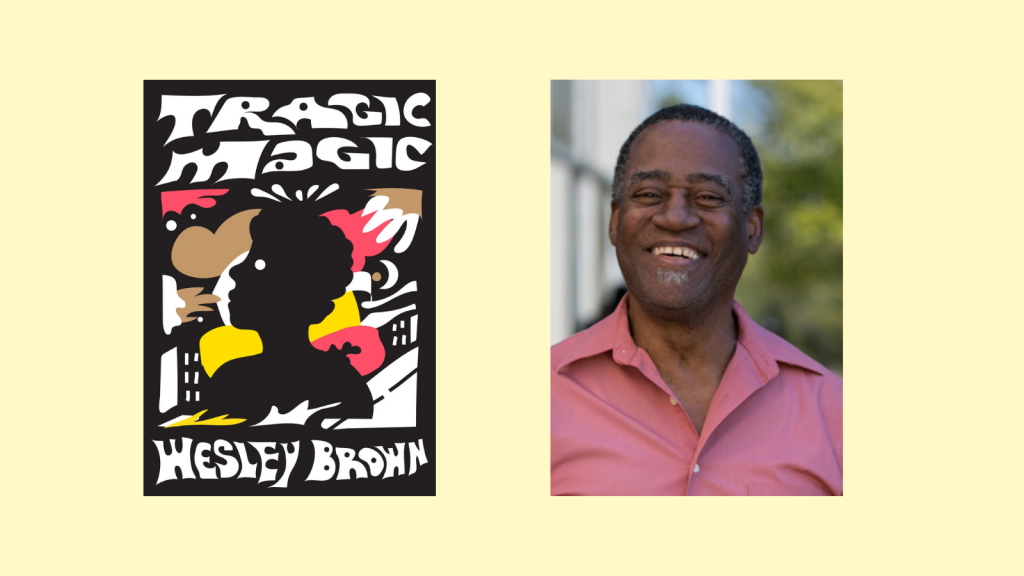

WESLEY BROWN is an acclaimed novelist, playwright, and teacher. He worked with the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party in 1965 and became a member of the Black Panther Party in 1968. In 1972, he was sentenced to three years in prison for refusing induction into the armed services and spent eighteen months in the Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary. For twenty-six years, Brown was a much-revered professor at Rutgers University, where he inspired hundreds of students. He currently teaches literature at Bard College at Simon’s Rock and lives in Chatham, New York.

Ryan D. Matthews (RDM): Thank you again, Wesley, for chatting with me a little bit. So Tragic Magic was first published in 1978. Can you share a bit of how the book first came into being, and what brought you into the story? And then maybe a little bit about how the republication came about.

Wesley Brown (WB): I had been in a Master’s of Creative Writing program at City College that I entered in 1974. Prior to that, I’d been incarcerated for refusing to serve in the armed forces between 1972 and 1973. I was paroled after serving 18 months of a three-year sentence. When I was released, I had a draft of a manuscript that I’d been working on while in Lewisburg, Federal Penitentiary. At that point, it was mostly a coming of age story of a young Black man dealing with definitions of masculinity.

After my release, a writer friend of mine suggested that I incorporate my prison experiences into the novel, something I was initially reluctant to do. But I realized the difficulty dramatizing my prison experiences as part of the novel, but that was exactly what I should do as a writer. One of my mentors at City College was Donald Barthelme, who encouraged me a great deal. And in my final semester, I was in a workshop with Susan Sontag, who showed some of my work to Ted Solotaroff, a Senior Editor at Bantam Books. After reading my novel, Ted wanted to publish it in paperback. He then sent the manuscript to Toni Morrison, a Senior Editor at Random House, who also admired the novel and published Tragic Magic in the fall of 1978.

RDM: You had some illustrious supporters there, that’s incredible. What was it like working with Toni Morrison as an editor?

WB: While Ted Solotaroff did much of the editing of Tragic Magic, it was Toni Morrison who committed to giving my novel a hardcover life that it might not have had otherwise. This put me in the illustrious company of other African American writers she championed during the 1970s, such as Henry Dumas, Angela Davis, Toni Cade Bambara, and Gayle Jones, and was responsible for publishing a generation of African American writers over a period of twenty years.

RDM: That’s a great story. How has republication come about?

WB: I was contacted by Erica Vital-Lazare, who is the editor of McSweeney’s Diaspora Series, which is committed to the republication of out of print and often neglected African American novels. I believe this series will challenge Grace Paley’s comment of many years ago, that, more often than not, the only thing that comes with publication is silence.

RDM: It’s great that the book will get a second life. It looks like it’s going to be beautiful. I love what McSweeney’s is doing with it. Moving into the book a little bit here — Melvin “Mouth” Ellington, is the protagonist, and he is an arresting character. He’s been released from prison after doing time, as you mentioned, as a conscientious objector to the Vietnam war. And, in some ways, it feels like everyone knows what’s best for Melvin but Melvin himself. He’s trying to connect with family and friends who don’t necessarily understand his motivations. And in other ways, he’s trying to understand his own motivations, why he went to prison, the value of his ideals. I’m curious, what do you think Melvin makes of his predicament?

WB: Well, Melvin is confronted by the reality facing many young men who were subject to the draft during the Vietnam War. Having been shaped by the dominant male hierarchy in America, Melvin is conflicted by his emotional response to the War through his attraction and disaffection from the tough exterior of many of his peers, the previous generation of Black men like his father, and the images of manhood embodied in the western movie icons such as John Wayne. However, Melvin fails, miserably, in his efforts to fit into any of these versions of manhood. His only defense against threats to his fragile sense of self is his ability to assert himself through his facility with language.

So, after two years in prison, Melvin is still unclear about the motivations that put him in physical jeopardy in prison. In many ways, this is a reflection of the hierarchies within society as a whole.

RDM: In most ways, it seems like the prison system — in its expansion and privatization and as a surrogate institution for handling severe mental illness — has degraded even since Melvin’s time. Which, after reading the book, would seem impossible, but I think is probably true. Melvin’s trying to, as you alluded, figure out the rules of this place that is so foreign to him, and so violent. Do you currently have any connection to the prison abolition movement?

WB: Not directly, but I’ve followed the incredible work of people like Brian Stevenson and the “Equal Justice Initiative,” that focuses on the disproportionate levels of incarceration, particularly among Black men. In 1972, when I was in prison, there were about 250,000 people incarcerated nationally. And in the nearly fifty years since then, there are now some two and a half million people incarcerated. This speaks to the historical aftermath of the Civil War when Black men were arrested for vagrancy and subjected to forced labor for seven years, which fractured families, irreparably, similar to the contemporary mass incarceration among Black and other men of color today.

RDM: Melvin, when he’s in prison, wonders if he wants to write, wonders whether he might be a writer, and other inmates almost pick him out as somebody who might be a writer. And you mentioned doing a little bit of writing in prison. In what ways do you think that prison informed your writing?

WB: I think my prison experiences informed Tragic Magic by expanding my understanding of how deeply the destructive conventions of male behavior are embedded in our culture. And Melvin discovers what Dostoyevsky understood — that if you want to understand the nature of any society, look at its prisons.

RDM: There’s a moment in the book when Melvin and his best friend Otis are fleeing from the police, who, when they catch up to these two suspects, they offer to release them if they have good stories to explain the fact that they’re running away. One of the cops says, “You see, if you’re a cop in the streets everybody’s got a story for you. If you hear good ones, this ain’t a bad job…You two fit a lot of descriptions and we could take you just on that. But we’d rather hear a story. A good one this time.” I was so captivated by that. What do you think is the value of a good story?

WB: The scene makes the point that the power of a well-told story can hold someone’s attention, getting them to listen to unpleasant truths about themselves, which they might prefer not to hear. Stories also have a way of diffusing, potentially violent situations through humor — which was the case for Otis and Melvin when they were accosted by the police. Ultimately, stories challenge what we think we know by providing more questions than answers, without the easy consolation of resolutions.

RDM: Absolutely. That plays into a theme in Tragic Magic. Melvin, and other characters in the book, have, I would say, some interesting views on political action. Many of the characters imagine as if one act can bring the system down. There’s Melvin’s refusal to serve, his friend Otis’s desire to destroy western films. There’s a character Jason who wants to use Attica as a model to bring the prison system down. It’s a story, in some ways, of learning that one act is not enough, that there are no easy answers.

You’re someone who has been politically active for a long time and knows well how slow the progress is. What advice would you have for Melvin about long-term activism and the value of those long-term commitments?

WB: I think it’s important for Melvin to remain open, to continue questioning received notions of reality and not be locked down to the belief that meaningful change can only be achieved through the shortest distance between where he is and where he wants to be — which is often viewed as a straight line. But to paraphrase the song by the former Dixie Chicks, there are times when you have to take the long way around.

RDM: Getting back to the book, these really are old themes for America. And Tragic Magic seems especially prescient — the handling of masculinity, and queer identity, and police violence — in ways that feel timely now but were probably just as timely when it was published. Having seen both of these eras up close, how do you conceive of the two? How are they different?

WB: I think as far as the protests by Black Lives Matter and other groups, as John Lewis said “to make necessary trouble” — challenging the systemic racism and inequalities in every area of institutional life in America — there is a common thread connecting the movements of the 1960s to the activism by embattled groups of people in this present moment. What is different are the ways in which horrific events can be recorded by social media, the murder of George Floyd and so many others, that go viral and galvanize large groups of people to protest in several parts of the country, simultaneously, that without the video footage would never have come to light.

Another difference is that the leadership of the current movements is amorphous and a lot more dispersed. This demonstrates an advance of what was problematic about leadership in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. This underscores the criticism made by Ella Baker, a pivotal figure in the formation of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, who once said: the movement had to move away from the cultivation of leader-oriented people to the development of people-oriented leadership.

RDM: That makes me feel optimistic in a way that I needed today. Were you involved with groups that were politically active during the ’60s?

WB: Yes, I went to Mississippi in 1965, and I was involved with the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee and the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party in the efforts to register Black people to vote. This was a few months after the Selma to Montgomery March and before the passage of the Voting Rights Act. In the late 1960s, I worked with the Black Panther Party in Rochester, New York, that was part of a move by a portion of the southern Civil Rights Movement toward cities in the northeast, mid-west, and west coast.

RDM: The character Theo in the book is a leader in the Movement, and there’s a great quote of his: “when its political initiatives fail, the use of violence becomes a logical extension of political policy…But unlike the government, we understand that although violence can be explained, it can never be explained away…” I thought that was such a poignant passage.

I’m interested whether you see parallels between some of those movements, the Black Panthers, and today with the Black Lives Matter Movement. The Left was, in some ways, so much stronger and more radical in the 1960s and 1970s, with the Panthers and the Weather Underground. And I’m interested in what we can learn from the past — what both those parallels and differences are.

WB: I would say that the movements of the 1960s and early 70s are part of a continuum. And what I see now is an expansion of the same issues and the different ways in which they are addressed. I don’t, necessarily, see the political activism of the Black Panther Party and the Weather Underground as more radical. But there were those in both groups that rejected using only non-violent protest to advance their commitment to bring about fundamental change in America — as Malcolm X said, “by any means necessary.” So in my novel, one of the “necessary means” considered is the use of violence — which Melvin comes to realize that, if like governments, activists for social and political change can explain away, they do it at their own peril, as well as the people on whose behalf they are struggling.

RDM: You talked a little bit about the power of language, particularly the power of language to instigate change, and how important it is to all of us who are concerned with its use. One of the many ways that the book is especially notable is its use of truly wicked dialogue. The “shit-talking” between characters feels singular. I know that you’ve also worked as a playwright, which seems like it would provide an understandably comfortable home for someone so adept at conjuring dialogue. What do you see as the advantage of one form versus the other to tell stories?

WB: I believe both have virtues that serve different ways of advancing dramatic action. I remember the playwright, Romulus Linney, once saying that dialogue in a play should be written with an ax, meaning that its effect is heightened when the language spoken by actors is stylized, having a knife-like precision, rather than attempting to approximate the meandering way people actually speak. In narrative fiction, the different voices on the page provide the writer with more opportunities to take imaginative leaps with language that can engage the senses of a reader but would make an audience impatient.

RDM: I love hearing about how people move between forms. Who are you reading and taking comfort in during these strange days of ours?

WB: Given the global pandemic, I’ve been reading The Plague by Camus, Katherine Anne Porter’s Pale Horse, Pale Rider, also some of Harold Pinter’s late plays and the poetry of Stephen Dunn, Lucille Clifton, and Joy Harjo.

RDM: Well, I hope for better days. Wesley, this was such a treat.

WB: I want to thank you, Ryan, for inviting me to do this interview.