Aimee Nezhukumatathil establishes her presence in the first sentence of this exquisite new book of lyrical essays. After the title of the piece – “Catalpa Tree,” followed by its botanical binomial “Catalpa speciosa” – she writes, “A catalpa can give two brown girls in western Kansas a green umbrella from the sun.”

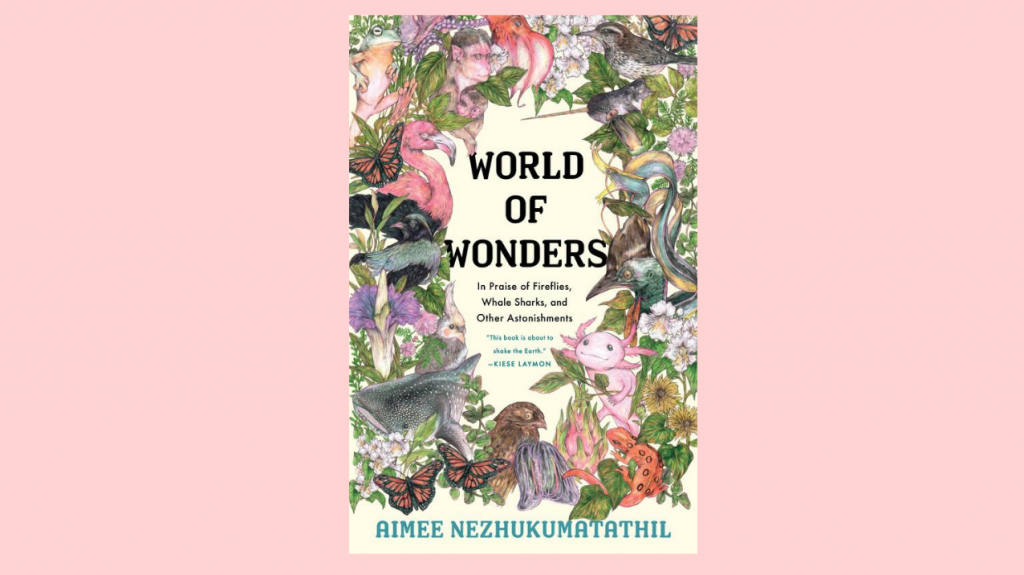

First, the reader understands that these chapters will center on beings in the natural world and that the author will pay some attention to the science that has tried to understand them. A quick look at the Table of Contents lets us know that Nezhukumatathil will write short essays centered on birds, insects, other plants, some mammals, and creatures of the sea.

The second sentence gives the personal context for those “two brown girls,” for any reader that had doubt: “Don’t get too dark, too dark, our mother would remind us …” This phrase immediately lets us know that these are personal essays that the author herself— the daughter of a Filipina mother and a South Indian father— will be the lens through which these natural objects are understood. Even at the very beginning of this book, I thought of something I had felt when reading Nezhukumatathil’s poems—this writer might agree with the quote (from Ezra Pound of all unlikely people!) that the poet Jane Kenyon kept above her work table: “The natural object is always the adequate symbol.” And here, that symbol places itself clearly in the discussion of race.

At the very beginning of World of Wonders, the author claims her place and her brown skin under that catalpa tree, protected by that “green umbrella.” Nezhukumatathil is proudly and profoundly staking her claim and making room for her concerns in the tradition of American nature writing, a tradition that has often felt confined and limited by its whiteness. It’s nice to know that she is not alone; just looking at the books on the table beside me, I see work by the poets Camille Dungy and Ross Gay, and the book of short personal essays by the biologist J. Drew Lanham, The Home Place: Memoirs of a Colored Man’s Love Affair with Nature, all of whom are working with similar ideas. As exhilarating as it is to see these writers-of-color expanding the possibilities of this tradition, we must remind ourselves of the work that still needs to be done. We only have to go back a few months to remember the terrified white woman calling the police because an African-American man was bird-watching in Central Park.

Much later in the book, in an essay centered on the potoo, a South American bird with a big voice but which is almost impossible to see because its coloring camouflages it against the trees it sits in, Nezhulumatathil writes,

Like the potoo, I grew up wanting to blend in—in my case, with my blonde counterparts—and why would I know anything else? I felt most seen in my childhood not by any television shows or movies but rather when I was in the outdoors, in forests or fields, by lake or ocean. I learned how to be still from watching birds. If I wanted to see them, I had to mimic their stillness, to move slow in a world that wishes us brown girls to be fast.

It is interesting to note that those lessons in stillness have shaped her not only as a writer but as other anecdotes in other essays in World of Wonders indicate, they have informed the way she teaches and the way she raises her sons.

Something of her method is suggested in that first sentence. The catalpa tree gives those “brown girls” a “green umbrella” to protect them “from the sun.” It is a vivid image, precise and chosen, an image that could find a home easily in a lyric poem. The sentences on stillness that I quoted above begin with a simile. These devices alone would be enough to suggest the lyric tone of these essays, but there are other choices Nezhukumatathil has made that use techniques she has learned from her important work in poetry.

As difficult as it is to define genres, particularly in their recent manifestations, it might be possible to understand “the lyric essay” as a personal essay that uses devices usually found in lyric poems to move around the central idea of an essay without stating it directly, as a writer would usually do in a discursive essay. For instance, in her essay on the “Firefly,” Nezhukumatathil jumps from description of childhood memories to science to a memory of her mother to indigo buntings and back to the science of fireflies with only a double break between paragraphs. She trusts her readers to make the associations between the elements, and I certainly did. The essay never felt fragmented and certainly came together in a quiet sense of loss.

Near the end of World of Wonders, the author returns to the firefly. She describes a literary moment and one with her children. And then she comes as close as she does anywhere else in the book to being explicit about her purpose: “It is this way with wonder: it takes a bit of patience, and it takes putting yourself in the right place at the right time. It requires that we be curious enough to forgo our small distractions in order to find the world.”

Aimee Nezhukumatathil is an important American writer still early in her literary career but who has already made significant contributions to our literature and our understanding of ourselves. The collection of powerful short essays written in direct, even crystalline prose, will always be central to our understanding of her work, even as it contributes to new ways we might all find to live in wonder.