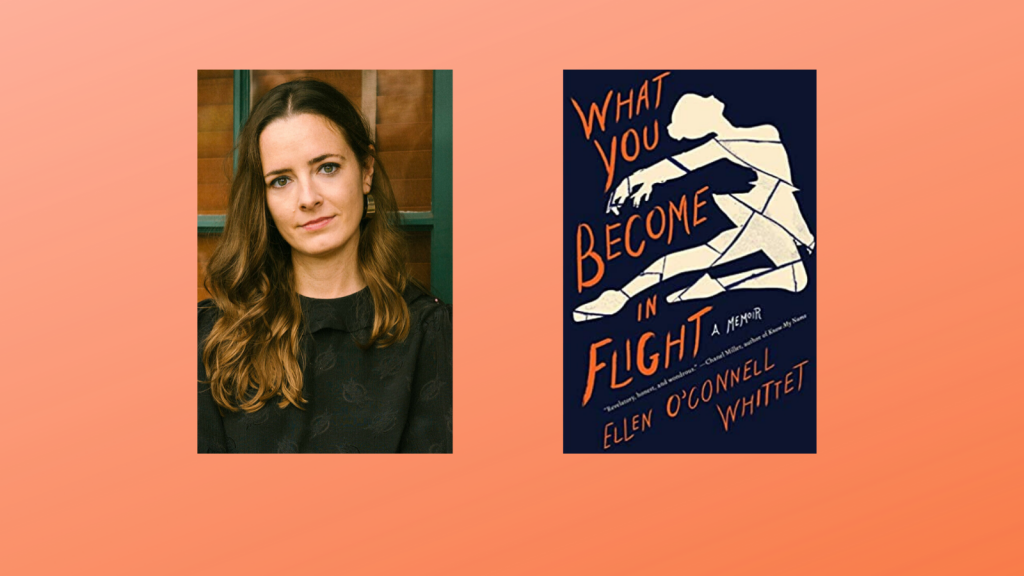

Ellen O’Connell Whittet’s essays have appeared in Paris Review, The Atlantic, Salon, the Ploughshares blog, and more. She’s a lecturer in the Writing Program at UC Santa Barbara and a recipient of the Virginia Faulkner Award. Her debut memoir, What You Become in Flight, is available April 14, 2020.

As a young adult, Ellen O’Connell Whittet is devoted to her career in classical ballet. But a spinal fracture incurred during rehearsal leaves her temporarily immobile on the floor of her parents’ house. After this sudden and traumatic loss, she’s forced to examine all the physical and psychological injuries she’s suffered on her journey to achieve perfection. Alone with her body for the first time, O’Connell Whittet is faced with the reality of dancing someone else’s choreography, her body a tool for someone else’s story. Only then can she allow her life as a writer to begin. Part chilling memoir, part ars poetica, What You Become in Flight illustrates all the horrors inflicted on young women before they can earn the right of being seen and heard.

This interview was conducted in March 2020. It has been edited for length and clarity.

Maya Dobjensky (MD): What lessons from your career as a dancer did you bring into your writing practice? Do you find the two come from similar sources of inspiration, or are they completely separate beasts?

Ellen O’Connell Whittet (EOW): Ballet is incredibly disciplined—it’s a daily practice. And some days are better than others, but you show up constantly to be able to do it at all. You have to set goals. This has served me in writing in so many ways. I don’t have a daily writing practice, and in fact bristle at those who do because I think it belies so much privilege. When the great writers of the past are held up as examples, like Trollope who wrote every morning, 250 words every 15 minutes, before he went to work at the post office, I just want to know, who was making his meals? Who was doing his laundry? Who was raising his children? We know the answer to that, of course, but I think writing can be as elastic or as rigid as works for each writer. When I have projects or deadlines, I draw from ballet’s discipline. I set daily word count goals, revise with the aim of perfection (impossible in any art form, yet ballet taught me to believe it was possible!), and feel very satisfied at the end of the day. I’ve carried that over from my young adulthood demanding I satisfy the audience I know is there or will be there.

MD: One of the major themes in your memoir is the limitations of language. Certain experiences, like joy and flight, can only be fully expressed through the body. There’s a fluency to this expression that requires an emptying of the mind, a total reliance on the physical self. Do you experience this meditative state when appreciating other art forms, or is it unique to dance?

EOW: I experience it with music too, and sometimes with visual arts, but I experience it most with dance. This isn’t because it’s more present in dance, but because that’s the language I know how to speak. So much of life and art exists beyond language, and I think paying attention to our bodies’ carefully tuned responses to what moves us, what lifts our hearts and spirits or matches the moods we’re in, can take us from our minds and deliver us into our bodies. That is exactly what a meditative state is—being in the present, free from our minds’ worries. Art lets us experience that kind of transcendent blankness, or else it replaces whatever is burdening us with emotional and intellectual movement.

MD: As someone with no real knowledge of classical ballet, I was struck by the ambition a dancer feels not toward greatness, but toward absolute perfection. I’m not sure writers or any other kinds of artists hold themselves to that impossible standard. It seems like there’s a relationship between perfection and the fleeting nature of dance, as well as its demand to turn the artist into art. Why do you think ballet demands so much from its followers compared to other art forms?

EOW: Ballet requires control over every single muscle in your body, so that totality of commitment and care makes it feel like it demands every part of your whole body. Even your face! Perfection in dance is impossible and yet always the goal, plus, of course, more than perfection. In addition to perfection, ballet demands that dancers personalize it, emote, feel their way through, so the perfection has to be automatic. It’s never the most exciting part of ballet, but without it, the best parts, the quality of movement and the feeling behind the movement, can’t fully exist. The dancer performs choreography created by someone else, so the dance exists only within the confines of that dancer’s interpretation and delivery. Dance doesn’t exist without a body doing it, unlike all other art forms, which have a score, or a manuscript, or canvas. The dancer is all of these things, so must be perfect.

And although it is physical, ballet requires intellect too. The best dancers are smart and thoughtful about the artform and their own contributions to it. Dance required memorization and recognizing patterns and problem-solving from the most minute level to the highest and highest-stakes levels. Because it’s a community act between dancer, choreographer, musicians, and audience, as well between dancers on stage, perfection is an important goal to keep everyone safe, and allow everyone to dance fully.

MD: I think in some ways, this memoir is a catalogue of pain, both physical and emotional. Moments of physical torment come in conjunction with rites of passage: pointe shoes are bought around the time of puberty, a first love and first heartbreak come into relief against the scene of a car crash. There’s a contradiction in this pain: on one hand the dancer must suffer silently in order to make her art appear seamless, and on the other, she’s desperate for someone to acknowledge and validate her suffering. In what ways do you think pain defines or shapes womanhood beyond the scope of ballet?

EOW: I’ve been considering this as I’ve prepared for my book to be released three weeks before I’m due to have my first baby. The pain that we consider biological and normal from adolescence to menopause is an organizing principle of each month, of the decisions we make about our bodies, and of the public nature of motherhood, which begins as soon as we start to show we’re pregnant and continues long after babies are born. I’ve had so many people comment on or touch my body since I’ve been showing, and it shocks me every time. There is pain in both wanting to have a baby and not wanting to have one, in both being and not being pregnant. This is not to say women are defined by motherhood by any means, but like ballet, it provides a lens through which to see the pressures of womanhood in one small slice: our bodies are public, commented on when they take up space, subject to scrutiny and criticism, and there is not enough structure or support around womanhood. We are asked to constantly perform, just as we are in ballet. Some of the pain is exhaustion.

MD: Much of this memoir takes place during your late teens and early twenties, during which your attitude toward your body goes through several metamorphoses. Has the process of writing and compiling your manuscript forced you to further reevaluate your relationship with your body?

EOW: In a lot of ways, writing this book made me have more compassion with my younger self’s obsession with how I looked because I recognized it was such an inevitability that I’d develop an eating disorder and sense of distance from my own body. I also felt my back injury flare up while I was writing, when I’d sit for too long or too many days in a row, so writing, in a strange way, forced me to pay attention to my pain at the same time I chronicled what happened when I didn’t. I went to yoga regularly and took walks to take care of myself while writing about the intensity of body trauma. It’s always hard revisiting pictures from my youth because I see how thin I was and have competing feelings of horror and nostalgia. But I also felt proud of my body, and like I had to pledge to be on its team more as I age.

MD: Caitlin, your understudy in a significant performance, is such an interesting character. She’s ambitious, dangerously competitive, desperate for attention, and worst of all, unashamed of these qualities. The other girls shun her for not being self-deprecating enough. Of her, you write, “She only carried through what all of us secretly felt: that other women existed to measure ourselves against […] That other women were just another device we used to punish our bodies with our naked, raw desire.” In telling this story, you could have easily vilified this girl rather than empathized with her. What made you decide to do the latter?

EOW: I never like to vilify anyone, even people who are clear antagonists, which I don’t think Caitlin was. We’re always acting through the lens of our cultural values, and Caitlin was only subject to the same forces I was. That chapter was one of the hardest to write—my agent kept sending back notes and questions about my own complicity. Getting to explore why I let that particular injury happen, and then why I danced on a broken foot, made me realize ballet and its demands only asked as much of myself as I was willing to give. Making myself my own antagonist meant Caitlin was a channel for that destruction without being its cause.

MD: Early on in the book, you delineate the origins of ballet as an art form of the bourgeois, one that celebrates homogeneity in skin color and body type. With contemporary figures such as Misty Copeland, where do you see the future of inclusion in the world of ballet?

EOW: Fortunately, there are many more now, although we still have a long way to go. When I was a teenager, I saw lots of ballet stars coming from Latin America to the U.S.—Carlos Acosta, Xiomara Reyes, Paloma Herrera, Herman Cornejo. Now the so-called perfection of ballet, encoded as whiteness, is being interrogated to allow for dancers of color to be held to something more interesting than a white standard, although they are still outliers in many major companies, including two in Europe that recently engaged in conversations about Blackface and Orientalist stereotypes. This season, American Ballet Theater was supposed to have their first Black Romeo and Juliet, although all their performances have been postponed to keep the public safe. New York City Ballet just cast their first Black Marie in The Nutcracker, and pointe shoe companies like Gaynor Minden and Freed are making color-inclusive pointe shoes. I love seeing how more stars are breaking white norms, but I think until artistic directors and choreographers are also more diverse, there will always be an imbalance.