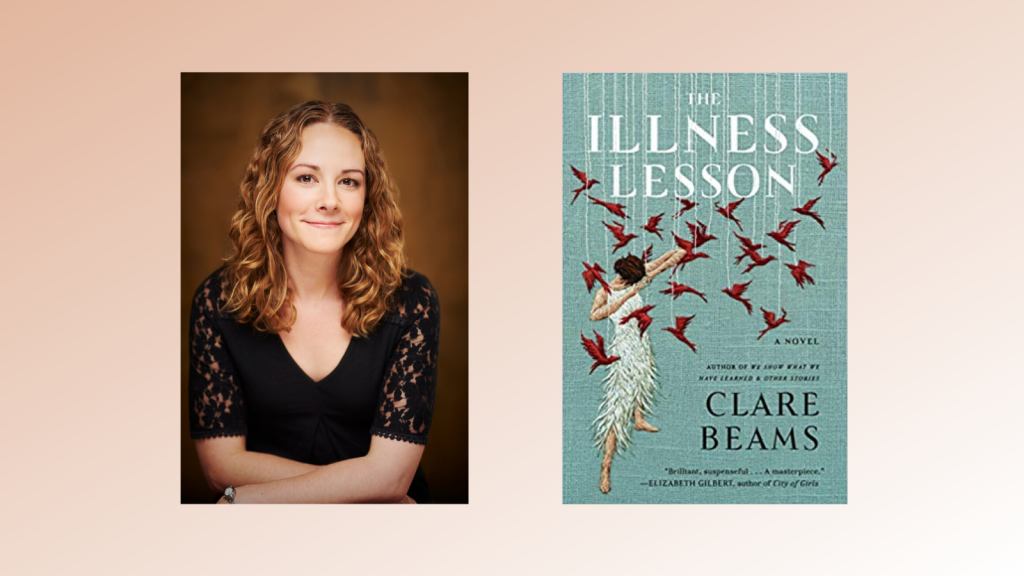

Clare Beams’ 2016 debut book of short stories, We Show What We Have Learned, won the Bard Fiction Prize and was a finalist for the PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize and the Shirley Jackson Award. Her fiction has appeared in The Kenyon Review, n+1, Ecotone, and others. Her first novel, The Illness Lesson, was released in February 2020 to the acclaim of The New York Times, Time Magazine, Vanity Fair, and more.

The Illness Lesson follows the sheltered life of Caroline Hood, daughter of the once famous transcendentalist thinker Samuel Hood, in her small Massachusetts town in the 1870s. When Samuel decides to open a school for girls that favors intellectual curiosity over sewing and etiquette, Caroline becomes skeptical that these romantic values can translate to the misogynist world her students will inherit. She’s also the only one to fear the otherworldly splendor of a flock of blood-red birds which have suddenly descended on the Hood’s land.

When Caroline’s adolescent students become sick with mysterious symptoms like rashes and fainting, she and her male colleagues initially brush it off as the dramatics of girlhood. A doctor is brought to the school to administer treatments to the girls, and Caroline, who is by now developing symptoms of her own, is horrified by his practices. What follows is an unflinching glimpse into a history which feels chillingly contemporary. The Illness Lesson is a strange and electrifying story about the power and prison of the female body, and about the contagion of silence.

This interview was conducted in March 2020. It has been edited for length and clarity.

Maya Dobjensky (MD): Images and landscape are so vivid in this novel. Certain moments hang in my mind: the trilling heart birds, the moment when Eliza and the other girls slip into the forest at night, Caroline’s dream of standing naked except for her arms adorned in bright red feathers. When you were drafting this novel, did you sketch the birds or map out the landscape?

Clare Beams (CB): Thank you! I do often start with image, as a writer, so I’m glad to hear these particular images are coming through. It’s funny—while I do think of my writing as being very visual, I’m pretty hopeless when it comes to the creation of anything spatial (maps, visual art, etc.), and I don’t tend to resort to actual drawing or mapping unless I need to make sure something hangs together and I’m not contradicting myself in some way. But I do pause and think about and embellish little set-pieces of imagery quite often, sort of lingering with my mental eye—even though a lot of this then has to be cut in revision, for the sake of pacing and the pruning of my own self-indulgence.

MD: The Illness Lesson prominently features a fictional text called The Darkening Glass by Miles Pearson. Each chapter begins with quotes from this fictional novel that converse with the events transpiring in the Hood household. What was your writing process like when creating a book within a book? Did you write an outline of The Darkening Glass?

CB: I did at one point have an outline and a whole mental map of the plot of The Darkening Glass, and the passages that begin each chapter were initially much longer. I was having so much fun with the over-the-top-ness of the book, with its melodramatic gothic nature, and I loved giving it a sort of shadow-presence in the larger novel, given that Samuel has tried so hard to suppress this book by his long-ago rival in his school and in his life. Ultimately, though, those longer passages were more fun for me than they were for the reader: an intentionally bad book is still a bad book, and it just does not make for good reading if you let it stretch out too long. So, I compressed and distilled things down to the very most exaggerated gestures that could—just as you say—converse in interesting ways with the main book.

MD: In an interview with The Believer, you said that you were so reluctant to write about the treatments the sick girls receive that you ended up rushing through the climax in earlier drafts. I can understand how this would be painful to write, as it was painful to read. I had a very visceral reaction to this section of the book. I started pacing my house, talking out loud to the characters, as you would when you’re watching a horror movie and you think you can convince a character not to go into the empty corn field. What was it like to force yourself to write something you were so uncomfortable with? Did you learn anything about yourself or your writing process during this exercise?

CB: Well, I can’t say I’m glad you reacted that way, but I can say it’s the reaction I had and the reaction I was, on some level, trying to produce in the reader. This novel is in many ways about a kind of slow build to a horrific place—and it’s about the forces, not all of them obviously evil, that make this place possible. In order for that indictment to land, we do have to see the horror. It took me a while to learn that, or to face it, anyway. Once I finally came to terms with the fact that the book required this of me, I tried, in the writing of the actual scenes, to be as precise and grounded and measured as I could, and not to allow myself or the reader to look away. It’s the looking away of the characters around these girls that allows these scenes to happen in the first place.

MD: Toward the end of the novel, I found myself wondering if the girls of the School of the Trilling Heart would exhibit physical signs of PTSD after what they endured, and if so, how those symptoms would be treated or ignored. Based on your research of female hysteria and other feminine afflictions, how do you imagine the girls’ PTSD would be treated?

CB: I think in all likelihood it really wouldn’t have been treated or understood at all. There’s a willful blindness to the realities of women’s bodies running through much of the time period’s medical literature (and I would argue we’re the inheritors of this blindness, and that it’s been corrected only imperfectly). There would have been, probably, a lot of “resting,” a lot of separation from the rest of the world. If symptoms were particularly dramatic there might have been further treatment for “hysteria,” which might or might not have looked quite like Hawkins’ horrific treatment, but which almost certainly would have carried condescension with it in some way.

MD: I read your novel just as the COVID-19 chaos was hitting the US, and I found myself drawing connections between the panic in the School of the Trilling Heart and the panic in our current climate. Particularly, I was thinking about who has access to health and health care, and how healing can be used as a tool of power and privilege rather than a right. Obviously, this wasn’t how you intended the book to be read, but often literature has a way of affecting its audience in ways the writer couldn’t have anticipated. How do you think the lens of the current pandemic will interact with readers’ understanding of The Illness Lesson?

CB: It’s so fascinating to me to think about the ways in which this book might take on lives I never foresaw for it. The pandemic is very clearly going to affect everything about the way we think about and interact with one another, and so it will probably affect the way this book is read too. Certainly, I think we’re watching decisions get made every day that are about privileging certain kinds of needs over other needs, and we’re learning a lot about who is helped and protected by various approaches to disease. We might do well to keep asking who has the most to gain from any particular strategy before we throw ourselves behind that strategy. All these kinds of questions, which we’re asking with new urgency now, are questions that are central to my novel too, in a very different context.

MD: Some of the short stories in your collection, We Show What We Have Learned, also explore illness from interesting perspectives. I’m thinking of “The Saltwater Cure”, in which a hotel promises to cure any ailment with several swims in its salt marsh, and “Ailments”, which features a plague doctor. Rob in “The Saltwater Cure” is infatuated with a client of the hotel and becomes obsessed with discovering her illness. Cassandra in “Ailments” is plagued by jealousy and lust, while the object of her desire is tormented by fear. In both of these stories, as well as The Illness Lesson, we see the ways in which contagion can affect the mind and soul just as much as the body. Can you talk about what led you to write about illness and wellness from these perspectives?

CB: As a writer I’m just endlessly fascinated by the slippery ways in which the body and mind affect each other. The body is its own mysterious and partially inaccessible region, and the mind can run into all sorts of trouble in trying to decipher what the body feels and experiences; and sometimes truths the mind doesn’t want to acknowledge can show up in the body first. I love all the weird richness that lives in these connections. I find fiction can take a lot of life from them.

MD: In a piece on the Ploughshares Blog, you wrote that female fabulist writers like Helen Oyeyemi and Kelly Link are often lumped together despite their very individual styles and voices. Why do you think fabulism has become a platform for contemporary female writers? Is there a danger or power in viewing this genre as female?

CB: I do think there’s something inherently strange about existing as a female in our current world. In general, women are perhaps a little more aware of living with strangeness in our bodies than men are (there was nothing like being pregnant to hammer this home for me, but it’s there in all sorts of ways). There’s also something surreal about the tensions women live with and inside: the things we’re told about ourselves and the tone we’re told them in so often don’t match up, and the disconnect to some extent defines our lives. Fabulism lets us get at a concentrated version of the strangenesses so many of us know intimately from our own lives (though I’m sure this is true for male fabulists as well). I certainly don’t think we need to view the genre as exclusively female, but it is true that there’s this whole invigorating tribe of women fiction writers who are writing, in one way or another, inside this genre, and that they’re some of my favorite writers working today.