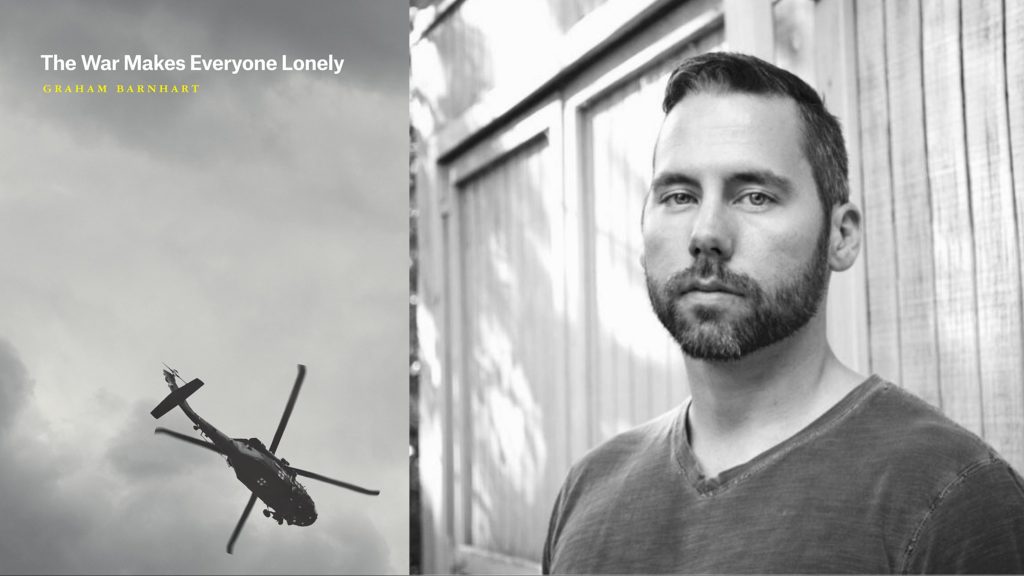

The War Makes Everyone Lonely, Graham Barnhart’s first book of poetry, is a haunting collection that confronts questions of memory and isolation, that stem from the duration and aftermath of Barnhart’s own military service. The collection of poetry can be delineated as part lyrical rumination, part narrative rendering that figures war as a physical space on a poetical map.

In The War Makes Everyone Lonely the opening inscription, “You are not a witness to the ruin. You are the ruin to be witnessed,” comes to inform every poem which springs from the page like landmarks; each instance of the poem and the speaker that inhabits it not a witness to the war but a kind of ruin to it.

This particular epigraph comes from General Orders No. 9 by filmmaker Robert Persons, a documentary about Georgia’s ongoing process of urbanization. Filmmaker Magazine describes General Orders No. 9 as “A synthesis of voiceover, music, and imagery, the film considers the possibility of finding meaning in a time of growing disorder. Starting with the establishment of one of Georgia’s centermost towns and ending with the urban sprawl to which it gave way, the film grounded by an occasional narrator…Whether he addresses the cosmos or the viewers themselves, he engenders a nostalgia that surely transcends the space in which the film exists.”

Barnhart’s poems perform a similar exacting work, with relays of stunning imagery and objective narrative interspersed with moments of music and subjective intimacy. The book is wise in its section-less structure that switches between scenes of military and veteran/civilian life (often in the same poem), in a manner that blurs the boundary between the two and showcases war, for the individual that survives it, as a non-linear, ongoing experience. And yet, the order of the poems which include three titled 1900, 300, 500 (for the times of day in military time) suggests a chronology that ultimately finds the speaker/soldier entering into a new day.

This tension between past and present is experienced from the very first poem in the book, “Belated Letter To My Grandmother.” In it, the speaker imagines a letter that could have been sent in response to his grandmother’s letter when he was stationed overseas but never was. When Barnhart writes,

And no, I don’t think I was afraid of dying.

Seven months isn’t so long a time. Unlike life,

war can be survived.

Like walking in the dark

he introduces the reader like a distant family member to the extended simile of the war, the ‘like’ and ‘Unlike’ giving poetic rendering for that for which there is no direct translation.

Such confessionals are balanced with the more concrete immersion of poems like the titular “The War Makes Everyone Lonely.” Here, in lieu of a hypothetical letter, the poem lets the reader listen in on a real-life phone call between the speaker and their sister while in a war zone. Surefooted lineation generates a mesmerizing scene that frames everyone within as adjacent to loneliness. At first the call seems to offer a connection. The speaker intones: “My sister had been receiving a lot of calls / from strangers. This is how she learns / her number is listed on an escort site.”

However, it soon becomes clear that a kind of dual listening is occurring. When the speaker reveals that: “I can hear wind ribboning the concertina, /and Allen’s boots on the roof as he brushes /snow off the dish,” the illusion is broken. The war has separated the speaker from his sister as much as it separates him from Allen who he can hear but not see on the roof or the strangers who in their desire to connect end up calling the sister but are denied. Loneliness abounds.

The book succeeds in tracking the fetishization of war. In poems like, “What’s it like,” which give gems like, “hot brass thick round as a lipstick shuttle”

Here, the instrument of war is held parallel to an instrument of beauty. Yet, beyond any false juxtaposition with beauty, Barnhart succeeds in mapping the ugliness of war. In “Pissing in Irbil,” the speaker encounters a Kurdish woman while relieving himself in an alley next to the rubble of a house. It is perhaps here that I should say that the universal legibility of this collection is a testament to Barnhart’s craft. There are often poems with specific subject matter that might be more accessible to members of the military. And yet, any didactic impulse gives way to a colloquial familiarity.

The only parts that do not fully succeed are ones that attempt to discuss something that hasn’t been mapped. In the still cinematic “Blocking An Imagined War Movie,” Barnhart’s speaker says of an Afghan boy, “He will limp the rest of his life / to the well, to the shura, at harvest /shoveling the wind with grains and chaff.”

Here the future tense of ‘will’ holds a paradoxical tension. Outside of an objective narration of the past or even a subjective remembering, it projects this suffering of the war to a future that hasn’t been written. The poem succeeds in showing the ugliness of war and even as a critique of the propaganda of war movies. But it does not necessarily add to the map, by now resplendent with legends of memory, isolation, and even healing.

Yes, there is also healing in the war which we track through Barnhart’s speaker, a military medic. It is physical in poems like “First Life,” in which the speaker saves someone else in the midst of an arresting array of white space. It is emotional in poems like “Somnambulant,” a sequence of couplets stitched together with laughter. And yet, it is not perfect. The tension between the objective narration and lyrical construction of the war-as-experience come to a head in the poem “Everything in Sunlight I Can’t Stop Seeing.” When Barnhart relays, “The black wrought fences continue / leaning into their rust, rigid and falling, and there / is no war in this but me,” the line break at ‘continue’ and the musical alliteration of ‘rust, rigid’ embody how the physical nature of the war obtains continuity within the individual. Despite healing a scar now exists on the skin almost like a map of the old wound.

In a time where lies about the Afghanistan war are just coming to light, this book of poetry is a refreshing breath of truth that avoids romanticism and offers, at times, a subtle yet searing critique. Indeed, reading the book it is difficult to forget the inherit problematic nature of the subject as well as an understanding that there are many narratives beyond the scope of what has been rendered. However, in operating at this scale, Barnhart, through the perspective of the individual, is not just able to poetically map loneliness or healing, but also the ruin that war makes for all times. If one believes George Santayana’s adage “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” then we simply need more.