It is a Saturday morning in early Spring and I’m sitting in a laundromat with my partner reading Kai Cheng Thom’s Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars: A Dangerous Trans Girl’s Confabulous Memoir. I’m about fifteen minutes into my wash cycle and forty pages into the novel when Rapunzelle, described so far as “an obsidian globe of a woman,” tells the unnamed protagonist how she met her lover Kimaya, the Street of Miracles’ trans guardian angel. Rapunzelle had become addicted to a drug that causes the user to shape shift, which she used to become lost to herself and to the world. One night she takes the heaviest dose she can find at a club on the Street of Miracles and shape shifts so rapidly and violently that she might have been lost forever, if not for Kimaya latching onto her and holding her through every transformation until she came down. As Rapunzelle gears up to tell our protagonist what Kimaya said to her when asked why she held on, I can feel the familiar sensation of tears welling up and a lump forming in my throat. When Rapunzelle says “She said to me because you’re worth holding onto,” (1) I let go and begin softly sobbing into the whir of washers and dryers. And I can already tell this book will not only change the game for trans lit, but it will also change me. (2)

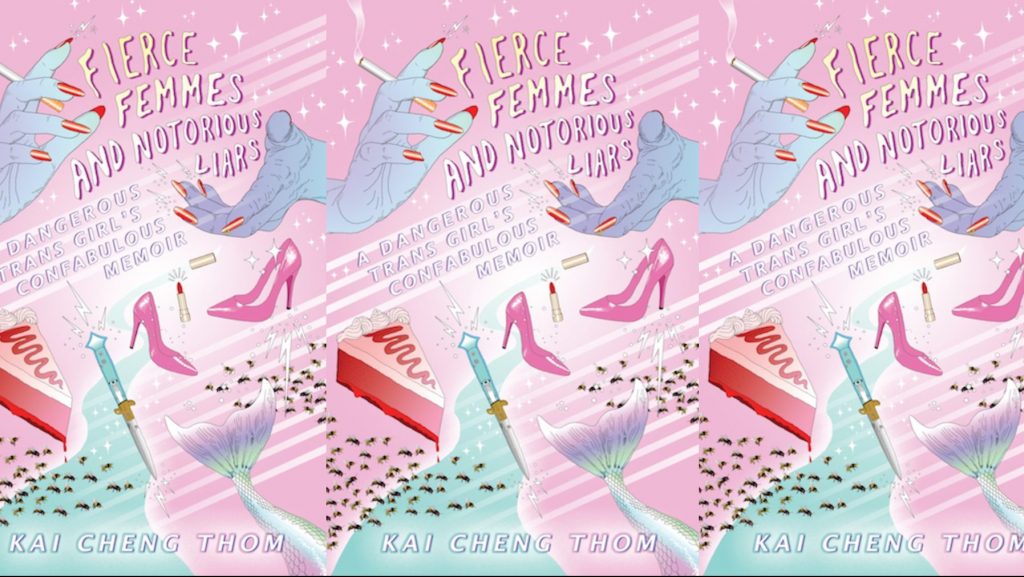

That is the kind of book that Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars is. It’s a debut novel of equal parts fact and fiction, fantasy and true crime, bildungsroman and memoir. It jerks tears, boils blood, tickles fancies, and punches you right in the feels. But there is far more to it than its emotionality or even its genre-queerness. It also, I believe, ushers in a new wave of trans literature and one that you should be paying attention to whether you’re trans or not.

Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars is a novel, or confabulist memoir, about a trans girl in her late teens whose name we never learn. She is raised by her Chinese immigrant parents in a “crooked house whose walls curved and bulged in the middle and narrowed at the top and bottom, like a starving person with a swollen belly” in a city called Gloom. (3) In the first section, called “Runaway,” the protagonist chooses to leave her parents, her younger sister Charity, and the doom and gloom of her hometown on the day that all the mermaids threw themselves on the shores to slowly die by mass suicide in seeming protest of the mess humanity made of the waters. She leaves Gloom “to become a woman” and gets on a bus headed for the City of Smoke and Lights. (4) Before she departs, we learn about the killer bees who have made her body a home, her ghost friend who became the only person who can make her orgasm, and her Kung Fu skills passed on by her father who was a Shaolin monk. The moment she arrives in the City of Smoke and Lights, our heroine (or is it anti-heroine?) is greeted by the mother of the femmes on the Street of Miracles, Kimaya herself. Kimaya introduces her to all the other femmes, helps her find an apartment, and hooks her up with Dr. Crocodile who oversees all the girls’ medical transitions, that is, in exchange for intensely wandering eyes and hands on their changing bodies. Readers will recognize elements of everything from magical realism to the trope of travel narratives in transgender memoirs just in these few details of the early plot. I summarize the plot in part one as the introduction to this review to begin to tease out some of the choices regarding style and genre that Thom makes which I want to suggest engender and enable a break with traditions and expectations in transgender literature, such as they are. These stylistic choices Thom makes early on also begin to characterize the protagonist as an unreliable narrator, another thread I take up later in this essay.

Things take a turn when Soraya, one of the trans femmes of color in the community based around the Femme Alliance Building (FAB, for short) and the Street of Miracles, is found murdered in an alleyway with the police refusing to acknowledge foul play. When Valaria, known as the Goddess of War to the femmes of the street, declares that it’s time to take matters into their own hands, she is met with Kimaya’s resistance and calls for nonviolence, patience, and love. The femmes are divided. Even Rapunzelle risks her relationship with Kimaya to seek vigilante justice. And in response to Valaria’s call, the Lipstick Lacerators are born. They begin to strike terror into the hearts of the cis men who terrorize the femmes of the street; each attack on the men they see as threats, oppressors, would-be murderers of trans femmes only escalates the tensions between the femmes and the sordid hordes of dudes who haunt the alleys and back doors of the Street of Miracles. In retaliation, the police organize a raid to catch the girl gang in the act and our protagonist makes a split-second decision that marks the climax – or perhaps just one among many – of the novel. The falling action centers largely on our protagonist’s growth as a person and the theme of forgiveness. However, readers looking for a happy ending would do well to remember that our protagonist claims early on she will detail for us “how [she] became the greatest escape artist of all time” and not to get their hopes up that our girl is meant for cozy condominiums, fancy store-bought dresses, and the life of a kept woman. (5)

Thom’s novel dabbles in fantasy, magical realism, and speculative fiction while bringing its own kind of ethos to writing about trans women that the protagonist characterizes early on as “dangerous stories.” These dangerous stories are meant to be ones told by trans girls like our heroine who might “cut out their own hearts and lock them in boxes so that awful guys on the internet will never break them again” or who “lost their father in the war and their mother to disease, and who go forth to find where Death lives and make him give them back.” (6) These stories are dangerous because they dare to move past the kind of life writing expectations that have constrained trans literature in particular. The protagonist tells us that the dangerous story she wants to tell is “a transgender memoir, but not like most of the 11,378 transgender memoirs out there, which are just regurgitations of the same old story that makes us boring and dead and safe to read about.” (7) And Thom does nothing if not deliver a dangerous story in the form of this anti-memoir. However, even dangerous stories can be located with literary traditions, and I will attempt to situate Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars within a tradition of writing to show how it works in and against it (and why you should care!).

At the risk of over-theorizing a dangerous story that speaks for itself, I introduce a genealogy of literature that begets Kai Cheng Thom’s (anti-)memoir and a cadre of work on transgender/transsexuality that might shed light on the importance of this book for trans literature and thought. This is not to say that her work is not in conversation with other kinds of works, notably Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s Dirty River (which Thom herself mentions in an interview), (8) The Vicious Red Relic, Love: A Fabulist Memoir by Anna Joy Springer, and even Larissa Lai’s Salt Fish Girl (also a noted favorite of Thom’s). (9) However, it is important to juxtapose Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars with work such as Jay Prosser’s Second Skins: The Body Narratives of Transsexuality, and more recent scholarship in transgender studies, most notably Andrea Long Chu’s piece “The Wrong Wrong Body: Notes on Trans Phenomenology,” (not to be confused with her more controversial pieces). (10) These two pieces in particular situate the longer history of trans life-writing that Thom flirts with without letting Fierce Femmes collapse into either fiction or memoir. My choice to juxtapose Thom’s work with Prosser and Chu is less about any of these authors’ larger canons, and more to do with condensing trans literary history over the last few decades into a couple of paragraphs in order to convince you, dear reader, that you should read Fierce Femmes, or read it again if you already have.

Ultimately, in pointing to these theoretical works I hope to give the reader tools with which to think Thom’s work without necessarily dictating what the reader should think about the novel itself. What I hope to reveal is the utility of thinking transgender literature now, in light of works like Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars, both in and out of the context of life writing and first-person narration that, whether out of necessity or out of desire to be heard or understood, primarily engages a cisgender audience. In this way, I am posing questions about trans literature now and how theories, of body narratives, and the wrong wrong-body provide a springboard for pushing the boundaries of what trans (or femme, or queer) means when authors like Thom center trans femmes of color and the communities they build.

To begin our brief foray into theoretical work on trans-ness, I look to one author who primarily engages the genre with which Thom plays: trans autobiography. Jay Prosser’s 1998 book Second Skins intervened at a critical juncture in the development of both academic queer theory, and the burgeoning field of transgender studies, which was itself necessarily both theoretical and literary. Specifically, his central argument about narration is that transsexuals must first narrate themselves to the clinician, and in a very particular and choreographed way, in order to be diagnosed with gender identity disorder. (11) Succinctly, he avers “to be transsexual, the subject must be a skilled narrator of his or her own life.” (12) Further, in discussing both the compulsion to narrate the self, and the “published return” to autobiography as narrative register, he contends that “if the published transsexual autobiographies are typically so crafted and engaging it is surely because of the narrative rigors of this diagnostic situation: because to be transsexual, transsexuals must be arch storytellers – or if they are not, must learn to become passable ones.” (13)

This theme of unreliable narration is one that has haunted both the clinical archives of transsexuality and the genres of trans life writing. Thom alludes to this history in the subtitle of her novel by divulging from the very beginning that Fierce Femmes is a confabulist memoir. In psychiatry, confabulation is the distortion, misinterpretation, or outright fabrication of memories to compensate for memory loss and Thom’s tale leads the reader through twists and turns that blur the line between fabulous and confabulous. Aspects of the novel such as the mermaid mass death by suicide, or the dead cop turning into a monument to the First Femme as a means of protecting the protagonist from murder charges dabble with magical realism by nonchalantly juxtaposing the fantastic with the mundane. But we as readers are never quite sure if we are in an alternate universe or timeline, or if we are simply seeing the real world through our protagonist’s eyes. That phenomenological aspect of Thom’s choice of first-person narration, wherein we are only aware of what the protagonist sees and experiences, blurs the line between this tradition of trans life writing as narration of transgender experience, and of speculative fiction where the suspension of disbelief is the basic requirement for entry into the story. While clinicians may have been trained to, at least historically, be suspicious of the transgender life as narrated by the person living it, Thom’s protagonist foundationally humanizes the experience of not being believed by telling us a story that’s both too good to be true and too good to be believed.

As a beginning of an answer to this question, we could further consider the way in which Prosser engages fiction in trans literature. Prosser’s analysis of Leslie Feinberg’s Stone Butch Blues, itself another cornerstone in trans literature, offers a means to think about trans lit beyond the autobiography. He calls Feinberg’s text a work of “transgenre,” which he defines as “a text as between genres as its subject is between genders.” (14) For the ways in which Stone Butch Blues both is and is not autobiographical or fictional, Prosser argues in favor of the utility of fiction for what it allows Feinberg to say that xe might have pulled back if writing in a strictly autobiographical way. Feinberg hirself claimed that fiction is “less than biography but more than lies;” (15) Prosser extrapolates that for Feinberg, “fiction is less factual than autobiography but truer, for truth and facts are not identical in hir usage.” (16)

In a parallel way, Thom’s novel is able to get at the truth of how trans femmes of color, and perhaps trans femmes and trans women generally, build and maintain communities without reducing those experiences to statistics, to straightforward politics, or even to “factual” generic conventions of autobiography. Instead, she confabulates, eschewing conventions which demand the truth of the matter. Thom rejects authenticity both in her generic form and in her content, or in Trish Salah’s blurb: “the first lie is that this book is a memoir, the second is that it is not.” One could read this refusal, this lie, as one meant to safeguard and protect the sanctity of trans femme communities. Alternatively, one could read this approach as one meant to taunt the cisgender reader bringing his or her expectations to a text that is not about him or her. Finally, one could consider the possibility that Thom merely takes a playful approach to genre, choosing to suture them together and see how they fit, rather than pitting them against one another or fully realizing any one of them.

If we who read trans life writing have seen, as Chu seems to suggest, all that can be expected in terms of innovation within the generic conventions of trans memoir, then Thom proves that the only logical conclusion for trans literature is to be and become genre-queer, to write in trans-genres, and to name the stakes of engagement on its own terms. In reading Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars, one has no choice but to engage the work on its own terms, even as we know, from the very title, that we are being lied to. In fact, at least one moment reveals that the heroine might not even fully remember what happens, hence her confabulations, (to borrow again that psychiatric language), upon the un-rememberable and unforgettable. In the chapter “The Lesson of the Bees,” our protagonist begins to recount coming across a beehive while innocently trespassing in a neighbor’s garden and surrendering to the coming onslaught of stings only to emerge unscathed, when she interrupts “Wait. Sorry. That’s not what happened. Here is what happened.” (17) She moves instead to tell it how it “really” was when the angry swarm found her in her room on a cold winter evening and some of them “crawled inside [her] lips and up [her] nostrils, into every orifice,” (18) before they fly off into the night, “except. Some of them stayed…They are still inside me. They will always be.” (19) And we can see that regardless of how the bees got there, they are there inside of her because every time someone touches her in romantic or sexual ways, no matter their intentions, the bees buzz furiously and create internal chaos that often pushes our protagonist to violent outbursts. One could interpret the bees, of course, as evidence of childhood trauma that resurfaces in moments of stress that trigger her fighting instinct. The fact is that it doesn’t matter whether we believe her when she tells us how the bees ended up inside of her, why they stayed, or what it was about a particular incident that triggered their buzzing; we have no choice but to believe her if we want to continue the story.

Ultimately, Thom’s Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars doesn’t smash generic conventions like her protagonist smashes skulls with Praying Mantis and Leopard Paw. Instead, Thom weaves together the elements that appeal to her in order to tell the story she wants to tell. In a style that Samuel Delany would call paraliterary, (20) she is able to exceed both the expectations of factuality and the generic conventions of existing forms, be they science fiction, magical realism, autobiography, or coming-of-age stories. Her genre-queer sensibility begets a novel, a memoir, an anti-memoir, and something somehow more than the sum of its parts that is, as Trish Salah notes again in that back of the book review, “if you read it right, a DIY instruction manual for changing your sex and the world.”

Notes

(1) Kai Cheng Thom, Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars: A Dangerous Trans Girl’s Confabulous Memoir, (Montreal: Metonymy Press, 2016): 49.

(2) In fact, nearly four years after its publication and after I read it the first time, I can now assure you reader that it has changed me and the landscape of trans lit.

(3) Thom, 7.

(4) Thom, 13.

(5) Often, the life of a kept woman is considered a high achievement for transgender women. Looking at some of the central characters of the TV series Pose and their relationships with cisgender men who, in exchange for confidentiality, pay for the living expenses of their trans women lovers. While the life of a kept woman is arguably not a happy ending, it would’ve constituted a version of one for a transgender (anti-)heroine like the unnamed protagonist in Thom’s novel.

(6) Thom, 3.

(7) Ibid.

(8) Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, “Creating a Lush World of Trans Woman Literature: An Interview with Writer and Fierce Trans Femme, Kai Cheng Thom,” Bitch Media, March 23rd, 2017, https://www.bitchmedia.org/article/creating-lush-world-trans-woman-literature/interview-writer-and-fierce-trans-femme-kai-cheng.

(9) Ibid.

(10) Andrea Long Chu. “The Wrong Wrong Body: Notes on Trans Phenomenology.” Transgender Studies Quarterly 4, no. 1 (2017): 141-51.

(11) It’s worth noting that ‘gender identity disorder’ has since been reclassified as ‘gender dysphoria’ in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. It’s worth also noting that the gold standard for models of care related to hormones for transgender people is the ‘informed consent’ model which does not require a psychological evaluation or diagnosis of gender dysphoria prior to the provision of hormones.

(12) Jay Prosser, Second Skins: The Body Narratives of Transsexuality, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998), 108.

(13) Ibid, 113.

(14) Ibid, 191.

(15) Ibid, 192.

(16) Ibid.

(17) Thom, 17.

(18) Ibid.

(19) Ibid, 18.

(20) Samuel Delany, Shorter Views: Queer Thoughts & the Politics of the Paraliterary, (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 2000).

Bibliography

Meyerowitz, Joanne. How Sex Changed: A History of Transsexuality in the United States. Cambridge: Harvard UP. 2002.

Stryker, Susan. Transgender History. Berkeley: Seal Studies. 2008.