Dr. Lisa Gruenberg is a physician, medical educator, and writer based in Boston. Her essays have been published in Ploughshares, Vital Signs, Hospital Drive, The Intima, a Journal of Narrative Medicine, and the Michigan Quarterly Review. Her short story, “Keiskamma,” won the 2012 Artist Fellowship from the Massachusetts Cultural Council.

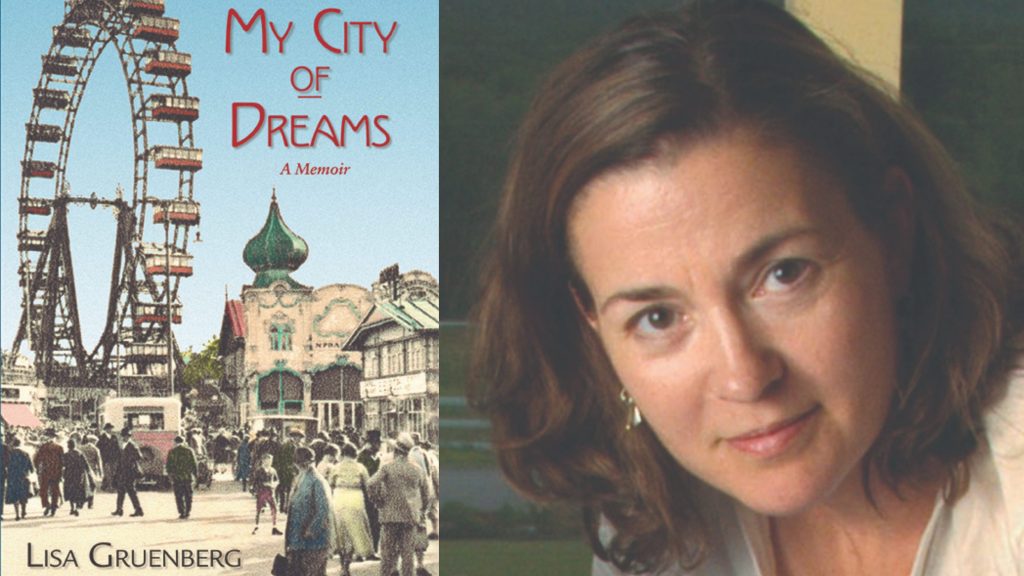

My City of Dreams is available now from TidePool Press

There comes a time in life when what you thought to be solid suddenly starts to dissolve. Lisa Gruenberg, a Boston physician and educator, felt it happen when images from her father’s past life began inhabiting her imagination. And changed her life. She became a writer. Gruenberg is still a physician and educator, but writing has become a life-enriching process after years of learning how to put down the stethoscope and pick up a pen.

The book begins in 2003 with Lisa and her family at their weekend home in New Hampshire. Her parents are visiting, and her elderly father has a flashback about Kristallnacht, when Nazi sympathizers broke into their home in Vienna, kicking his family out, stealing some items, then ransacking the place. This was very different from the joyful stories her father told her when she was a child.

Old men are inclined to repeat their stories; and Harry Gruenberg often unfolded his childhood tales. But like many who endured and escaped the Holocaust, he largely suppressed the horrific events that occurred before he fled to England in 1939 at the age of 18, and made light of what happened after, his long internship and imprisonment by the British and Canadians, and the loss of his parents and much of his family. It was only very late in life that he began erratically and inexplicably to relive scenes from his past, speaking suddenly in German, and yet moments later having no recollection of having done so. He has a recurring nightmare about being buried alive after discovering that his parents didn’t die at Auschwitz, but, in fact, had been shot or pushed into a mass grave in the forests outside of Minsk in Belarus. He speaks his sister’s name for the first time, and acknowledges his daughter that he has no real memory of Mia, who had disappeared into Germany in 1941 when she was just fifteen years old. His memories of Mia were, in fact, largely replaced by memories of Lisa as a child.

The story grows into a multi-layered drama of a family sundered by war, rich with moments of startling clarity from Lisa’s aging and disoriented father, a hymn to his beloved Vienna, the search for the others of his family as reconstructed or fantasized by Lisa, while she goes through her own personal catharsis. Lisa seems to immerse herself in her father’s past to a degree that is sharpened by her own emotional journey, doing extensive research and, ultimately, reaching a point of emotional identity with Mia.

The writing of a simple narrative is one thing: “My City of Dreams” is both more difficult to achieve and much richer in detail, because it tells several stories at once, with a variety of techniques. Harry Gruenberg’s twisted tale becomes interwoven with that of Lisa and his family, told with fragments of song, personal letters, primary source materials, photographs, family dramas, scenes, stories, fantasies, and dreams that gain their own narrative force. Like the best collages, the whole becomes much more vivid than its components. In the course of this fine book, we see the growth of Lisa’s skill as a writer, the changing dynamics of her family, her husband, Martin, and their daughters, and the evolution of their own stories into the larger drama, which touches all aspects of a multigenerational family, diverse in characters, histories and dreams.

While one can talk about the complex technique by which Dr. Gruenberg has created this book, it seems far more pertinent to note the emotional heft My City of Dreams can evoke. Whatever it reveals of the lives of these characters, there is surely enough to touch at the history of any reader.