The Czech writer Jaroslav Hašek is singularly known in English for his long and rambling novel, The Good Soldier Švejk, which follows the adventures of a bumbling recruit through the first World War. It was originally published serially in four volumes, ending only with the author’s premature death in 1923. By contrast, “A Rendezvous with the Censor” comes in just over 1,000 words, but conveys in that space the farcical humor and healthy skepticism of bureaucracy that are the defining characteristics of the much longer tome. I first encountered this short story in the early days of the current US presidency and the parallels in “A Rendezvous with the Censor” to our current moment struck me as unnervingly uncanny. The story was first published in 1911 in the magazine Karikatury, the same year in which Hašek founded the Party of Moderate Progress Within the Bounds of the Law, a satirical political party that has its origins in a pub — at the Golden Liter in the Vinohrady neighborhood of Prague (not to be confused with the Golden Tiger in the Old Town, where presidents Václav Havel and Bill Clinton shared a beer with another Czech author, Bohumil Hrabal, in 1994). Apart from his illustrious career as a politician, Hašek actually made his living as a journalist, and one can imagine that the scene depicted in “A Rendezvous with the Censor” might come from personal experience. It amounts to a warning tale, which throws into sharp relief the maddening absurdity inherent in the process of censorship, and is an indictment against obstructing the work of journalists with threats of violence. But for all the weight of its subject matter the story is also very funny, something that I hope comes through in its rendering here in English.

~ Meghan Forbes

New York, September 2019

A Rendezvous with the Censor

by Jaroslav Hašek

I had been invited many times to visit the censor and have a little word with him, but I’d always declined, because I had a vague sense of dread at the prospect of standing before that man. I have to say, I suffered from an idée fixe that the man would simply cross me out.

I can’t quite describe to you how I imagined it exactly, but it was a very unpleasant sensation, always connected with shivers down my spine.

Eventually I resolved to visit him nevertheless, and inquire about his general opinions. I judged him to be a person of poor mien, capable of anything, but I was wrong because what I found was a refined gentleman, who smiled at me agonizingly and asked that I be so kind and take a seat.

“We can have a little talk,” he said, “and I hope that you’ll correct your opinion of me somewhat. I do confess, that sometimes I commit some foolishness…”

I waved my hand to perform a gesture of dissent.

“No, believe me, I tell you in good faith that I sometimes perpetrate various foolish things, but it’s not my fault!” He chuckled sadly and asked that I examine his skull closely.

He had a very low forehead, and a shrunken skull.

“They’ve written about me,” he said, “that as a young boy I fell from a tree and banged my head on the ground, that I fell on my noggin, but that’s not true. My head was smushed shortly after birth when a near-sighted doctor sat on it, and as a consequence I’ve got this characteristic smushed skull. Initially they assumed that I wouldn’t survive, and if I did, that I’d be feeble-minded, but thanks be to God, I pulled through, and today I am the censor. Even still, I sometimes suffer headaches and perform some foolish things. Sometimes, sir, I do not confiscate downright insults to the church, and so forth. Around four years ago, for example, I let slide the sentence: ‘He bared his cross patiently.’ Now sir, you know who bore his cross, and that was our Savior, but here the expression referred to some cobbler. As soon as I recover, however, I fear no hurdles and set back about my work with vigor. You have no idea, honorable sir, how these sly and cunning writers and journalists today know all the tricks of the trade. They write such seemingly innocent things that only on further reflection does a person find the hook in it. After all, as Tolstoy says: ‘One claw is caught and the whole bird is lost.’ I also confiscated that sentence by the way, since it was made public at a time when a certain important figure tore his hunting fur on a thorn bush.

“And to show you just how cunning they are, consider for instance this sentence: ‘He stood leaning against a tree, looked into the storm, and pondered.’ It’s a sentence that on the face of it is insignificant, inoffensive, but that’s only on the face of it.”

He stood and began to pace about the room.

“Observe that written side by side are the words ‘storm’ and ‘pondered.’ Good, it might seem innocuous enough to you, but I didn’t let that sentence go, I had to confiscate it, because the word ‘storm’ will most markedly lodge in the mind of the reader and a reader acquainted with the psychological method begins to caste one’s mind back over storms in general and might say that there are also storms of another sort, apart from the natural phenomena of the heavens: there are also political storms, riots, sir, demonstrations.”

Still pacing:

“And then they are smashing windows, crying: ‘Blast the government, down with them, blast the police!’ They throw stones, and, sir, am I to allow that, me, a civil servant? And so I simply take out my blue pencil and cross out the sentence. I don’t like it at all when someone writes, for instance: ‘And he thought all kinds of things.’ Sir, there are loads contained in that ‘all kinds of things.’

“To think all kinds of things, that’s downright sedition, that’s an offense against the public law and order. To think all kinds of things, well that can amount to treasonous intellectual expression. They suppose that a person can think whatever one likes, as long as the offense is only in the form of such expressions. And what goddammit is a thought? A thought is an expression of mental activity! An expression, I say, and we have a code of law regarding expression.

“Believe me, I have to be very careful that I sniff out everything that could be lying in hiding. I don’t dare even overlook the sport’s section in the papers.”

“And pardon me, Mister, but I think you recently confiscated this sentence: ‘Those are true Chinese conditions.’”

“Of course. I crossed it out with my blue pencil because I’m well informed by the papers that there’s a revolution this very moment in China. So if someone writes in this day and age, when a goddamn Chinese revolution is prevailing—‘those are true Chinese conditions’—I think that anyone would see in that a call to mutiny. And as long as there are soldiers on the side of the revolutionaries in Nanking, I can’t help it, I have to confiscate the next day all news on the advancement of the Chinese revolution, because that’s anti-militarism. Someone asks, well what’s China to us? And their right, and yet how they devour the news, and oh how they devour it!

“And it’s from this news that they put together a newspaper. Is that not enough to drive you mad? You have for example news that the general population in China is in the hands of the revolutionaries. That’s a mutiny, sir, that’s a rebellion, and now you put that in the hands of the people. The newspapers are, sir, blight, disorder of the first order, just like everything that’s printed; but I tread all over it.”

He took from the wall a large pencil which hung like a decoration below some pictures, and said: “Have a look at this pencil. It’s everything. Some bloke has his pen and ink, but I have my pencil, a pencil goddammit. With it I disperse everything, I cross it all out, and I show them how I can raise hell.”

I made my leave of him quickly, since he started to gesticulate with his pencil under my nose, and I saw clearly that he would cross me out too, without mercy.

Originally published in Czech in the magazine Karikatury (Caricatures) on Dec. 11, 1911

Translation by Meghan Forbes

Special thanks to Barbora Bartunkova for her clever solutions to a few translational quandaries.

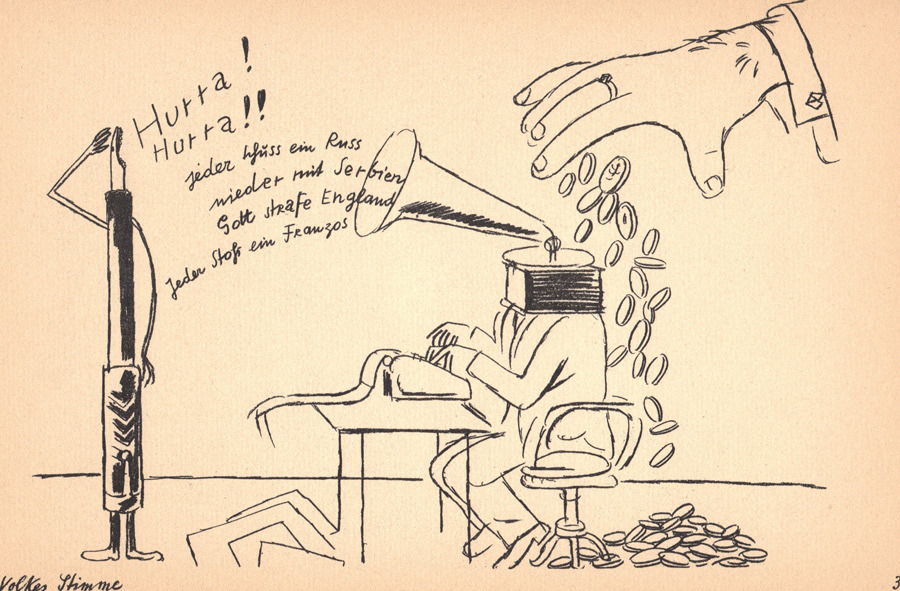

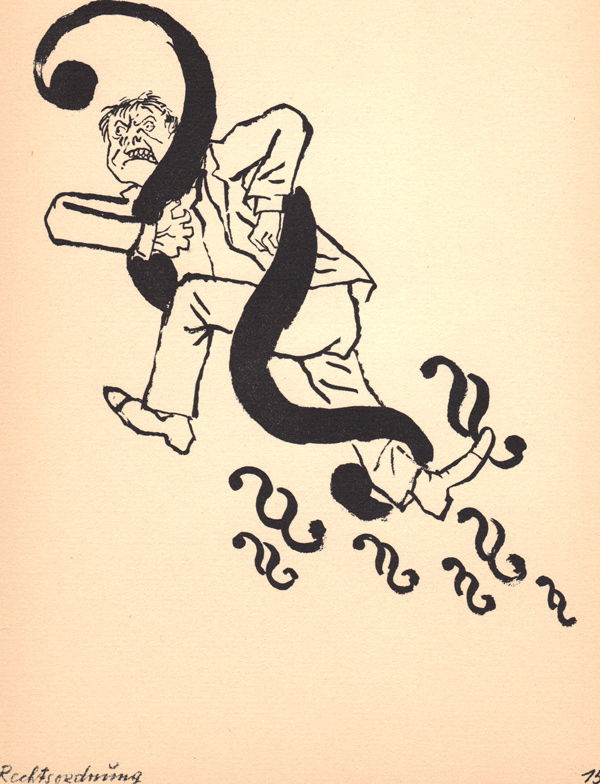

The two featured images are from “Hintergrund,” which consists of seventeen drawings by George Grosz for a 1928 German performance of The Good Soldier Švejk. (“Hintergrund” can mean “backdrop.”)