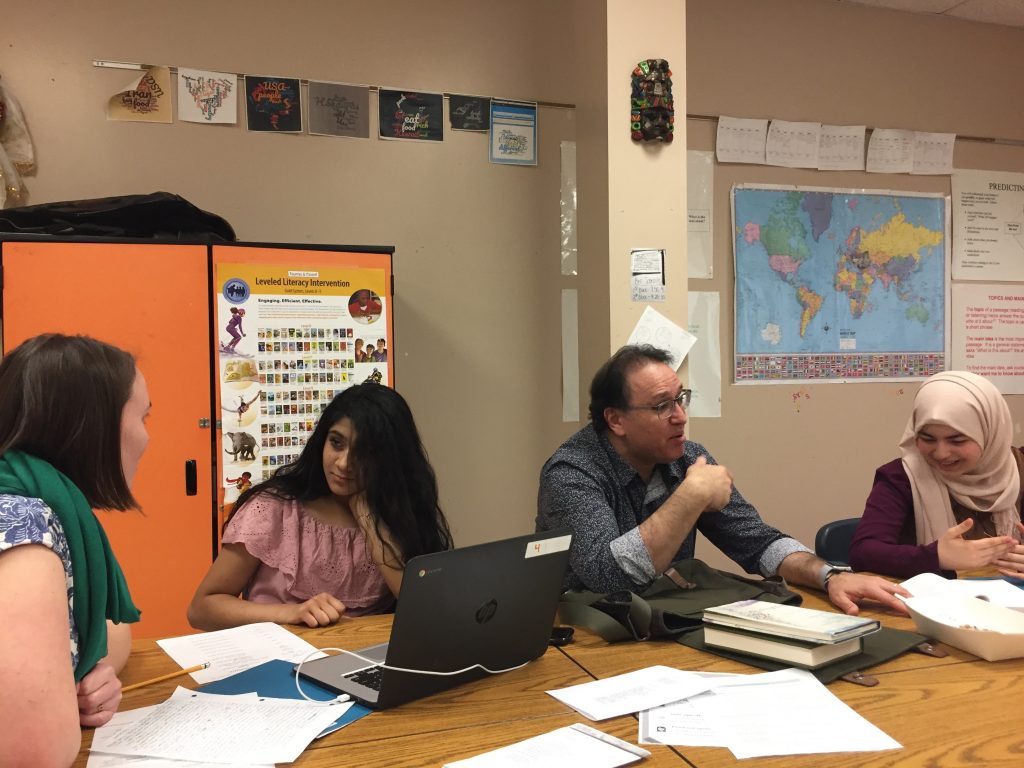

Interested in where writing is happening in your community? Today we have an essay on “Carrying Ourselves Across,” a community partnership between 826michigan and the Michigan Quarterly Review. 826michigan program volunteer Megan Berkobien founded and designed the classroom self-translation workshop at Ypsilanti Community High School, and our Editor-in Chief Khaled Mattawa is a guest poet and teacher in the program. Here, Megan introduces her pedagogy of literary translation and describes the joys of telling one’s own story.

We also share a selection of EVERYTHING YOU FIGHT FOR AND GAIN: Stories from the workshop Carrying Ourselves Across: The Art of Self-Translation, from student Wendy Canjura, who writes in English and Spanish.

What comes to mind when you think of literary translators working in the United States today? Who are they? What do they look like? What languages do they speak and translate? Most importantly, what is their relationship to those languages—have they been speaking them their whole lives (and who have they been speaking to)? Did they learn them later? If so, how?

If the first picture that comes to mind is of a scholar—and such a picture often defaults to a white, often male, academic—with a lifetime of formal experience with the language they’re translating into, then you’re likely not alone. And this image maps, at least partly, onto reality; a recent study reports that a majority of surveyed literary translators in the US identify as white, and many hold advanced degrees (though a majority identify as women).

There is, of course, nothing wrong with the kind of expertise we associate with professional translators; working between cultures requires careful and critical consideration of not only the texts in question, but also the power inequities that are trafficked and shaped through language and literature. In this sense, translation is an art and deft cultural, material labor. This does not, however, excuse the lack of equitable representation in the field. If literary translation is to be more than a profession, if we are to live it as praxis, as so many of us try, then things—including our own approaches—need to change.

Luckily, when we open ourselves up to it, another pressing reality becomes visible: the world of translation measured in pauses and in poetic but hesitant tongues, translation that gives itself up to ambiguity to make space for the many.

The many: families, neighbors, and friends recounting the tales that have moved them, sometimes even their own. These are our world’s most frequent translators, and yet they are often not afforded the title and its associated cultural capital. Perhaps that’s because their workspaces are informal—as with kitchen-table translation—their “finished texts” more ephemeral, or perhaps it’s because the language they’re translating into—often on behalf of loved ones—isn’t the one they grew up speaking. (Translation, for all of its rhetoric of collaboration, is not free from the pressures of cultural gatekeeping, especially when you attach the adjective “literary” to it.) So while their work isn’t always for pay and sure, it doesn’t always explicitly fall into neat literary categories, it is translation that gets to the heart of the task: reworking, reimagining, and reviving stories across languages and cultures.

In order to highlight this reality, we’ve put together this collection of stories from the second iteration of the 826michigan workshop “Carrying Ourselves Across: The Art of Self-Translation” at Ypsilanti Community High School. The task was, on the surface, a straightforward one: the student authors and translators, all English-language learners, would chronicle their experiences in one language and transpose them into another. They would carry their stories, as they had done their own bodies, into a context legible to their newly imagined audiences.

But this is more than thinking about translation as a tool of pedagogy. Any practicing translator knows that moving from one linguistic and cultural context to a second (or third) requires more than “knowing” languages. In moving through the translation process, translators must consider what cultural associations or emotions certain words carry beyond their linguistic content. But we don’t call it baggage, because it’s part and parcel to who we are as communicating beings—we call it art.

While the tales may be largely autobiographical, they are still literary in nature, if we consider the ways that they shaped their experiences into tales, and made sure to invite the readers into the scene with them by using sensory details. And because students wrote their own stories, they managed to dispel some of the authorial anxieties associated with translation (tropes of loss and incommensurability, for example).

The stories that emerged are foregrounded by themes of travel and dislocation, and also point to the funny pleasures of making your way: spontaneous dances with mom, actually enjoying raw broccoli, and returning to one home to realize you already have another. This entanglement is, of course, part and parcel of translation practice, especially for students who are entering different spaces, and, in some ways, different lives. But that’s both the beauty and challenge of translation, of carrying (ourselves) across—we never truly arrive in the singular.

MY FIRST TRIP, by Wendy Canjura

I am translating from Spanish to English. I wanted to show that here, in

the U.S., there are more opportunities for us. Some of the difficulties were not knowing the words in English and where to puts commas and periods. I am most proud of my English and writing.

When I was six months old, my parents took me for the

first time to El Salvador. I don’t remember anything about my

first trip to El Salvador. But my parents showed me pictures

so that at least I would have an idea of what it was like. When

I saw the pictures, I asked my parents, “Who is that girl in the

picture?” and they told me that the girl in the picture was me,

only in another country.

I grew up in El Salvador believing I had been born there but

when I was seven years old my parents started to tell me that

I had been born in the United States. They started to show me

my birth certificate that was different from my siblings’ birth

certificates because the birth certificate was in a different

language that I couldn’t read or understand. The years went

by like that until I was thirteen years old, when my parents

told me, on Valentine’s Day 2016, that I had to travel to the

U.S. for the first time to Los Angeles, California where my aunt

lived. I only visited a short time but I realized that here in the

U.S. there are more opportunities than in El Salvador because

here the government helps people more and there is more

education for us. I stayed with my aunt and in a year and a half

I traveled to Michigan where I was born. I could get to know

the place where I was born and where my parents lived in the

past. It was so weird and at the same time it was beautiful to

know where my parents lived and where I was born.

In 2018, I traveled back home to my parents in El Salvador

to celebrate my quinceañera (my fifteenth birthday). It felt very

good to see my parents again.

MI PRIMER VIAJE

Cuando tenía seis meses mis papás me llevaron por

primera vez a El Salvador. Yo no me acuerdo de nada de mi

primer viaje a El Salvador. Pero mis papás me mostraron fotos

para que yo tuviera la idea de cómo fue. Cuando yo veía las

fotos les preguntaba a mis papás, quien era esa niña de la

foto? y ellos me decían que esa niña de la foto era yo solo que

en otro país.

Yo crecí en El Salvador creyendo que había nacido ahí pero

cuando tenía siete años mis papás me comenzaron a decir

que yo había nacido en United States. Ellos me comenzaron a

enseñar la acta de nacimiento que era diferente a las de mis

hermanos y también porque era en diferente idioma que no

pude ni leer ni entender. Y así fueron pasando los años hasta

que tuve trece años. Mis papás me dijeron un día de San

Valentín del 2016 que tenía que viajar por primera vez a U.S., a

Los Ángeles, California donde vivía una tía. Solo venía de paseo

pero me di cuenta que aquí en los U.S hay más oportunidades

que en El Salvador. Porque aquí el gobierno de U.S. ayuda más

a las personas y también porque hay más educación para

nosotros. Me quedé a vivir con mi tia y al año y medio viajé

hacia Michigan donde yo nací. Pude conocer el lugar donde

nací y donde vivieron mis papás antes. Fue muy raro y a la vez

bonito saber el lugar donde vivieron mis papás y donde yo nací.

En el 2018 viajé de regreso a casa de mis papás en El

Salvador para celebrar mis quince años me sentí muy bien al

ver de regreso a mis papás.

Wendy Canjura was born in Ann Arbor, Michigan but her parents are from El Salvador, so she considers herself a Salvadoran. Her mom and dad are who inspire her because they have given her a lot of advice and have shown her that despite the circumstances, you must always move forward.

EVERYTHING YOU FIGHT FOR AND GAIN: Stories from the workshop Carrying Ourselves Across: The Art of Self-Translation

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This publication would not have been possible without the time, dedication, & support of the following people:

Teachers Anisa Bega Liz Sirman

Volunteers Meg Berkobien Luis Miguel dos Santos Luiza Duarte Caetano Jessica Flores Pat Gold KeAndra Hollis Luke Jackson Graham Liddell Júlia Irion Martins Susan Morrel-Samuels Susan Ruellan

Project & Publication Designer Meg Berkobien

826 Project Coordinator David Hutcheson

Editorial Intern Sarah Willis