Juan Abreu’s words first appeared in Michigan Quarterly Review‘s Fall 2001 issue. We revisit them today in honor of Reinaldo Arena’s birthday.

What follows is a translation of the first chapter of Reinaldo Arenas: A Memoir of 1974 (A la sombra del mar, Casiopea Publishers, 1998) by Arenas’s friend and fellow dissident, Juan Abreu.

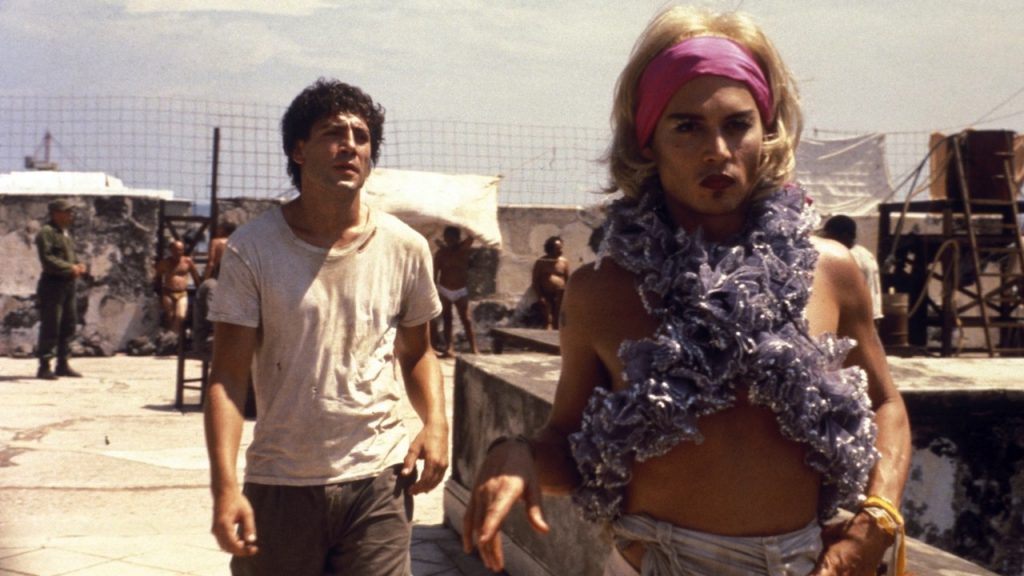

A Memoir of 1974 is a complementary text to Before Night Falls, the critically acclaimed autobiography (recently made into a movie) by Cuban writer Reinaldo Arenas. The book consists of 50 “prologues,” as the author calls them, written from December 1974 to June 1975 in Havana; it is a testimonial to Arenas’s attempts to hide from the police, send his manuscripts abroad, and escape from the island—and Abreu’s efforts to help him—during this period of time.

Abreu, a writer, journalist, and painter who currently lives in Barcelona, painstakingly recorded these events because, as he states in the first prologue, “if something happens to me, it is important that people know what happened and how.” Abreu did in fact run the risk of being jailed at any moment; being a friend of Arenas, hiding his manuscripts, and helping him leave the country, he was closely watched and constantly followed by the state police. Abreu’s record of the events of those eight months seethes with an immediacy, desperation, conviction, and vitality which set it apart from memoirs written after the fact, under the protection of exile and the distortions of hindsight.

The memoir is also a homage to friendship and the power of literature; it is the story of two young men, united by books, persecution, exile via the Mariel boatlift in 1980, their critical stance toward Cuban exiles, and the founding of the literary magazine, Mariel.

This first chapter stands alone as a testimonial, a cry of anguish, an S.O.S. and a homage to a friendship worth risking one’s life over.—Jennifer Gabrielle Edwards

I’ve been trying to find him for two days now, to no avail. In a note I picked up from one of our designated spots, he says that he’s alright; he also says where I can find him on the 9th, 10th, and 11th of December [1974]. He adds that he has had to change his sleeping place, but fails to explain why. We always had two or three hiding places (a hole in the ground covered with roots, under a rock, etc.) where we would leave messages wrapped in a piece of nylon. If there were suspicious people lurking around one hiding place, we could always use another one. On the 11th, for example, I’m supposed to meet him at 8:00 p.m. at the Lenin Park movie theater, but I can’t go because state security agents are staking out my house and shadowing everyone who enters it. Including my little sister, who’s just a kid. This situation lasted for several days. But the surveillance would increase and decrease for reasons I never understood. That day, after a visit from Oneida, Reinaldo’s mother, things changed. This was no surprise. She came on Wednesday, the 11th. Absolutely frantic, she couldn’t bear waiting in Holguín any longer to find out what was going on, so she came here. I feel terrible for her, how she tries to hide her anxiety, holding a bag full of things for her fugitive son. We seem to be acting out one of Virgilio Piñera’s stories. How could she come to the house of the only person who knows where her son is, knowing (as she must) that the police follow her everywhere? Well, she’s not alone, in fact she’s accompanied by quite a few tough guys, all wearing the usual uniforms and sitting in the Alfa-Romeos, also typical of the apparatus of repression. Since the moment she left we’ve been under constant surveillance. They don’t try to hide or dissimulate their presence, they want us to know that they’re there. I try to explain to Oneida that she shouldn’t tell anyone we know where Rey is. Emphasizing the word NO ONE. Which means, most importantly, that she not say anything to her sister, but I don’t know if she’s understood. I don’t even know if she’s listening to me. She’s completely dazed. Enormous rings under her eyes. Exhausted face accentuating her robust peasant’s body. Her eyes betray a defenselessness which I have, at times, noticed in her son. But she is also incredibly strong. She only breaks down, briefly, when my mother wraps her arm around her shoulder, trying to console her.

I’m writing this on Monday the 16th. I hear a motor outside; is it them? I write because I want these things to be known. If something should happen to me, it’s important that people know what happened and how.

Saturday, the 14th. I still haven’t been able to find him, and I’m almost positive something terrible has happened. I go to the place where he used to sleep, knowing he won’t be there because his note said he had changed sleeping quarters. But this time he didn’t indicate to where. Maybe he didn’t have time to write it. Maybe he didn’t know where he was going when he wrote the note. The cardboard boxes he used to protect himself at night from the cold and dampness are still there in the sewer. They were never enough. He made a kind of niche with the boxes, which he stuffed with newspaper. He also stuffed crumpled-up newspaper pages under his clothes. He looked like a Martian, but he kept warm. “At least this newspaper finally serves a purpose, aside from its official function as toilet paper,” he said, smiling, as he flourished a Granma.

In that area of the park at dawn, a thick fog descends down to the knees and engulfs the landscape. Although the openings to the sewers were nearly covered by grass and Rey tried to seal them with leftover boxes from his bedding, the fog still managed to get in. When I went to see him early in the morning, he would emerge as if from a page by Lovecraft; who, incidentally, is one of his favorite authors.

When I don’t find him in the sewer, I go to the designated site for leaving messages, but there’s nothing there. I’m sure that something has happened. He wouldn’t have gone anywhere without telling me. Without specifying another meeting place. There are only two possibilities. Either the police found him and he had to run away or he decided to leave the park, although I can’t imagine why. If they caught him, they might have put him in jail, or maybe he committed suicide, if he had time. He always has a jar of pills on him that my brother José had gotten through his job at the state hospital. He specifically asked for a drug that would kill him if he took enough of it. And we made sure of it. I’m certain that he wouldn’t hesitate to take them. Arenas had said, “Make sure they’ll kill me. I’m not afraid of death, all that’s left of my life is a never ending escape, and death would just be an escape from reality. But jail would be horrendous, squalid. Jail, I’m afraid of.”

If he managed to escape, he had planned on going to Oriente to look for his mother. Hoping beyond hope, I go to the bus stop. It’s dark now, and my sister and my wife are already there. We left the house together to confuse the police and they insisted on coming with me. The little cubicle where we wait is completely dark. It’s on a road that borders the park and leads to Calabazar. A woman in her forties, with her two little daughters, is also waiting for the 88 bus, the only one that stops there. She approaches us. She says: “I was afraid to talk to you. But when I saw that there were women. . . . It’s been really bad around here,” she adds, “there was a shootout here yesterday because of some chicken thieves; they got rid of the bag of chickens, but the police caught them later. That’s what I heard . . . and on Saturday this place was crammed full of police . . . ” (at this point the conversation starts to interest me). “The DTI[*] was here, the state security, a ton of patrol cars, yeah, they were after a fugitive, they did a shakedown and everything and they brought in the dogs and they stopped all the buses and put the dogs on board because he had left some clothes. . . .”

“But did they get him?” I ask, now sure that she’s referring to Rey.

“Yeah, they found him after, on Tuesday, with a book,” she replied.

With a book. It has to be him. But how does this woman know that they found him with a book? Lenin Park is a horrible place, although I suppose the official version and the propaganda for tourists say and show something else. Still, we used it as a meeting place for a while, and we had some very good times here, I must admit. And on several occasions, it saved our life. Which is to say that it saved us from dying of hunger. In the park, thanks to some bureaucrat or the Fifo himself, they’ve set up kiosks where you can get milk, cheese tarts, and even candy and toffee. Without a rationing card, “freelance.” Everything extremely expensive, naturally. But who cares about that when you’re starving? When there wasn’t a croquette or a glass of that pseudo-soda, guachipupa, to be had in all of Havana, there was always Lenin Park. The Park is located south of the city and at first it was pleasant, but then it became plagued by mosquitoes, weeds, and neglect. Like everything else here. This must be the country of good beginnings and gruesome endings. It has a reservoir, an outdoor amphitheater, a Japanese amusement park that was never finished and which halfheartedly functioned for a while. A Tea House. And since there are almost no motels for screwing anymore, it’s also a giant open-air motel. Now they’ll have to add to the tourist brochures that for a time this park was the hiding place of the most important young writer of the island, who, being an artist, and a man of integrity, had to flee from the police of the “First Free Territory of America.” Perhaps this little addendum will attract more dollars and they’ll even thank me for having taken the initiative.

I go back to the bus stop. In the conversation with the woman, I’ve found out something about what happened. Although nothing is sure. I consider the possibility that the woman’s account isn’t entirely true. First of all, because she no doubt got her information from other people, who in turn got their information from others. They’ve used the only free form of communication possible in Cuba: “Lip-radio.” The one thing I’m sure of is that something happened here last week. I think: numerous policemen and other security apparatus were mobilized. And they found him. What other fugitive would be caught with a book? It has to be him. But there are holes in the woman’s story. If the police found him on Saturday how could they have captured him on Tuesday? How could he have managed to stay in the park until Tuesday surrounded by all of those policemen, who he must have known were there? How did he manage to leave me a note? I saw him on Saturday morning without any problem, and we had agreed to meet again on Wednesday. So it must have been Sunday when he left me the note that said where he would be until our next meeting. In other words, where he’d be on Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday if something happened before our meeting on Wednesday night. It didn’t say anything about Sunday, so that was probably the day he wrote it. If this is true, the woman was mistaken and the police deployment didn’t take place on Saturday. If you take into account that the woman related her version of the events a week after they occurred, and, naturally, none of this really interests her, except as a topic of conversation, there’s no reason to think that her version of the events is accurate, by any means. Another motor outside. But I’m so sick and tired of it all that I don’t even bother to look out the window anymore to see if they’ve finally decided to search the house or take us away, or whatever. I keep writing. I want to make clear that for my sister and my wife, who accompanied me today, this was simply an excursion. They don’t know anything about any of this.

The possibility that he has managed to slip away is remote. He’s most likely been captured. Alive or dead. Getting captured alive is the worst thing that could happen to him; by now he would have been subjected to any number of interrogations about his manuscripts, how he sent them abroad, the friends who have helped him. They’re obviously furious that Rey has managed to elude them for so long right here in the capital of the island-estate they so tightly control. I don’t think they will get him to talk, but even if he doesn’t, it’s likely that they will come for us. These are days of uncertainty and restlessness. And terror.

Some clothing, a couple pocket mirrors, a knife I brought him, and a few books, The Iliad, The Odyssey, The Magic Mountain, and others I don’t recall, all must now be in the hands of the police. And the manuscript of an autobiography called Before Night Falls he had begun writing, not because death was imminent, he said, but because he could only write as long as there was sunlight, as he had no other. He planned on writing it in the style of the Spanish picaresque novels. I remember how during one of our meetings under a remote palm tree, he read to me what he had written so far. A couple of notebook pages. It began: “I have always been an extraordinarily ill-fated human being.” And then he went on to enumerate a devastating list of the calamities that have befallen him from the moment of his birth. Maybe the police haven’t confiscated the manuscript, because Rey kept it wrapped in nylon at the foot of that same palm tree under whose shade he read me his work. If he had it on him when he was arrested, we already know what awaits that manuscript.

So, what was the writer Reinaldo Arenas doing hiding in Lenin Park? Waiting for a chance to escape from the country. Waiting for someone to get him out. Around the 18th of November, a young Frenchman came to our house. He appeared during one of the many blackouts that have become an everyday part of our lives. We all happened to be home at the time. He’s a tall, athletic man and he said the password, Book of Flowers, and had the sinus medicine which we used as an additional precaution because it was made known by different means, and was created by Reinaldo and us. We had decided that if the person knew Book of Flowers, but didn’t have the medicine, he was a Cuban agent. We asked for more proof, information about our friends in France, we listened carefully to his French (my brother José speaks it quite well), and we made him sweat from anxiety under the glare of the kerosene lamps that barely illuminated the scene. Of course, even after all that, we didn’t believe a word he said and assumed, at least for the time being, that he was a top agent trained by Cuban intelligence for just these sorts of cases.

We are extremely careful. I arrange a meeting for Saturday, two days later, in the Novedades movie theater. Why the Novedades? Because Bernardo Morejón, a completely trustworthy childhood friend, works there as a projectionist and he’s agreed to let us use the projection room as a meeting place. An isolated place, away from suspicious eyes. My brothers and I discuss and make these decisions together. My mother sometimes participates, but never offers an opinion. When we’re leaving, she tells us to be careful. My father continues with his daily routine as if nothing were happening. He’s the type of person that, if you tell him atomic missiles are on their way to Cuba, he wouldn’t lift his eyes from the domino game he was absorbed in. This for me represents the greatest wisdom.

When Joris Lagarde (that was the Frenchman’s name) leaves and after letting a prudent amount of time go by, I start looking for Reinaldo. I find him in his sewer, wrapped in newspapers and boxes, ready to turn in for the night. Rey is elated and says that he must be the man he was expecting and that in any case he can’t afford to pass up any opportunities. We wait anxiously for Saturday to come.

The police are still staking out the house, but they’ve let up a bit. At least that’s how it seems to us. Maybe we got lucky with the blackout during Joris’s visit. It’s incredible that they still haven’t noticed him. If they followed him to the Deauville Hotel, where he is staying, then they will surely follow him when he goes to meet with me. He seems to be extremely clever, but he’s in a strange city, and here a foreigner stands out like a kangaroo in a tuxedo, as my beloved Raymond Chandler would say. I’ll have to tighten my security measures to make sure they don’t follow me when I go to meet him. At this point it’s impossible to change the meeting time, so I have no choice but to go.

Bernardo has kept a lookout ever since he came to work at noon, and he hasn’t noticed anything strange or unusual. I arrive early after having circled all over Havana, getting on and off buses between stops, hanging off the backs of others, until I’m sure I’ve lost anyone who might have followed me when I left the house. Even though I jumped over the back fence and left via F Street, instead of 4th, which is in front of the house. All of that, in addition to our usual diversion tactics: when I go out to make contact with someone, my brothers, my sister, my wife, and even sometimes my mother leave at the same time carrying baskets or some sort of bundle under their arms and then they disperse in all directions. They try to draw the attention of the police and make them follow them. It seems to have worked. So far. I hang out near the movie theater and keep an eye out for anything suspicious.

The Frenchman arrives at the appointed time. He doesn’t seem to have been followed. I wait another couple of minutes and then I go in and take him to the Novedades projection room, where I update him on the situation and explain how we’re going to meet with Rey. Joris says that he has also taken precautions so that he won’t be tailed and that he will follow my instructions to the letter. As I’m leaving I tell Bernardo that if he’s questioned, to blame me for the whole thing and pretend he knows nothing about it. To say that he had no idea what was going on, and that I used him. He says no way, that he’s sick and tired of these assholes and that they should go fuck their mothers. “Typical barrio Poey” I answer, and we laugh. Then I tell Joris to follow me a few paces behind, to not lose sight of me no matter what and to do everything I do, no matter how crazy it may seem. And we set out for Lenin Park.

We get to the Park late that night. We find Rey in a thicket, where we had agreed to meet. Lagarde informs Reinaldo that the boat he had planned on using to take him to Florida was confiscated. He seems to be an expert in these sorts of expeditions. The guy evidently feels terrible about this and Rey, for whom this is a devastating blow, tries to comfort him. We’re sitting in a circle, illumined by a small flashlight, in this dense thicket we have crawled into. Joris gives him everything he has, his watch, his pens, an underwater fishing knife. We decide on another escape plan that Lagarde promises to carry out as soon as he leaves Cuba. I get the impression (and later Rey expresses the same feeling) that I’m speaking with a Martian. Surely he’s a Martian if he can speak freely about when he is leaving and when he will return. Especially about when he will be leaving. We leave Reinaldo in poor spirits although, as always, he tries to remain hopeful.

The next day, I meet up with Joris again in the projection room and give him some manuscripts. He puts them in some sort of inside pocket in his jacket. He tells me not to worry, that they won’t catch him. I trust this man, I couldn’t say why. I give him the name and address of some friends in California so that he’ll send me a postcard from them when he gets to Mexico. This will let us know that he was able to leave without any problems. He memorizes everything. He’s quite something, this Frenchman. I say goodbye to him with great affection and the feeling that he’s an old friend. He’s leaving next Tuesday, and once out of the country he’ll get in touch with friends in France as well as with Rey’s editor. Maybe they can do something. Joris also takes a declaration with him, a kind of S.O.S. from the underground, as Reinaldo described it. Rey addressed it to the youth of the world, and it relates his days as a fugitive and prisoner.

Days go by and nothing happens. Rey is in a desperate situation. It’s not just the fear of being found. There’s the hunger and the cold and not having a roof over his head. The loneliness. I go to visit him whenever I can, and we talk for hours. He needs company. We plan literary discussions, to cheer us up. Whenever possible, I take from the little food we have and bring it to him. But everyone is hungry, and in any case there’s no money because we earn a miserable wage. Every so often we all chip in so that he can buy something from the Park’s kiosks.

We talk. The story of his escape could be a chapter from Hallucinations. Welaugh about that, and he gives me his version à la Fray Servando: “I run out of the police station in the midst of this tremendous fuss over a thermos of coffee which the policemen are fighting over, and I dive into the sea. I swim frantically under water and when I come up for air, I’m in front of the Guantánamo Naval Base. Thousands of lights are flashing, green, red, a mob of starving alligators chase after me. I’m shot at by machine guns. I climb a tree. I hug the tree.”

He talks about writing another S.O.S. to clarify what the UNEAC really is. But he doesn’t have time. We talk about his next novel, the third of his Pentagony series, Celestino Before Dawn, which comprises Singing from the Well, The Palace of the White Skunks, The Color of Summer, Farewell to the Sea, and The Assault. He never stopped making plans, in the situation he was in. He said that he was going to get a house by the sea so he could write in peace. That if any one of our meetings turned out to be the last, to not worry about him, that “we’d meet on the other side.”

We’re talking in Cuba, the First Free Territory in America, according to what the radio announcer just shouted as I write. Arenas also spoke of another project he wants to do. A trilogy consisting of Hallucinations and two other books based on great figures of Latin American history. He was considering Bolívar. His idea was to relate the story of the history of the continent based on three great men. Things that now he’ll never be able to do. Words, rhythms, he will not reveal. Cadences that will never be. Why? Because in this “entirely free” country you can’t even write in jail anymore, as those who are now in power did. The prime example being Fidel Castro himself. One cannot be a true artist in this country and participate in the official state culture. Of this I am sure. The only thing left for us is to flee. Escape from this hell, any way we can, and save what has been written. This is all the future holds for us. If we’re lucky.

What will become of us? I wonder at this desolate hour. Despondent, expecting the worst, we’re overwhelmed by the impunity of power. What will become of us? And another thing: can they really do away with us? We, who despite being harassed or jailed, as is Reinaldo’s (and many others’) case, we wait for our time to come doing what comes most naturally to us, writing. Who, despite everything, walk along the beach under the glittering sky and on the whirling sand that reflects the morning sun. What can they possibly do, if Rey, in the midst of such a horrifying situation, can manage to stay calm and to smile. What can they do if the happiness of the persecuted is the most absolute.

And then I think: the only thing Arenas loved were the waves, and there is the sea, untouchable and perfect.

And so I think Reinaldo is right: after the betrayers and the cruelty and the peace and the unpredictable, we’ll see each other on the other side, and we’ll reach for each other’s hand. That’s how it will be, simple, like all things lasting. And in the shade of the sea that envelops us, we’ll sit and wait for the waves.

Translated from the Spanish by Jennifer Gabrielle Edwards

- **Departamento Técnico de Investigaciones (Department of Special Investigations)