“Work on good prose has three steps: a musical phase when it is composed, an architectonic one when it is built, & a textile one when it is woven.” These words come from the brain of 20th-century philosopher and cultural critic, Walter Benjamin. But they’ve been reimagined by Vermont-based artist and author Frances Cannon. In her new book, Walter Benjamin Reimagined: A Graphic Translation of Poetry, Prose, Aphorisms, & Dreams(MIT Press), Cannon has extracted Benjamin’s various compositions and woven them together, with whimsy and an eye for negative capability.

There are many words for what this book is: a “graphic translation” of Benjamin’s personal life and his writings on topics such as childhood, the art of collecting things, class and gender politics, flâneuring, etc. It is an “encyclopedia of fragments.” It is an illustrated map of Benjamin’s brain filtered through the pen-and-ink artistry of Cannon’s brain. At times, it is almost impossible to know if the words we are reading are Benjamin’s or Cannon’s, and there’s beauty in knowing it is probably both of them at once. Walter Benjamin Reimagined becomes a sort of literary equivalent of Max Richter’s arrangement of Vivaldi’s “Four Seasons.” A reconstruction. A hypnotic tribute.

Within these beautifully illustrated pages, readers are witness to a blending of voices, a bending of genres, and a blossoming of thoughts. This book is a must-read for broody thinkers, book collectors, anyone wrestling with existentialism, and for those looking to tap into their inner youth. It’s a joyous invitation to seek out and discover fragments of Benjamin, fragments of Cannon, and, undoubtedly, fragments of yourself.

Frances Cannon is also the author of the graphic memoir, The Highs and Lows of Big Little Frank and Shapeshift Ma (Gold Wake Press, 2017); a book of poems and paintings, Tropicalia (Vagabond Press, 2016); and a collection of poems, Uranian Fruit (Honeybee Press, 2016). Her writings and graphic essays have appeared in Vice, Prompt Press, The Iowa Review, The Examined Life Journal, Edible Magazine, Electric Literature, and Vol. 1 Brooklyn. She received her BFA in poetry/printmaking from the University of Vermont and an MFA in creative nonfiction from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. She currently teaches at Champlain College, Vermont College of Fine Arts, and the Shelburne Craft School in Vermont.

Frances Cannon spoke with Michigan Quarterly Review about the origin of her Walter Benjamin project, how she pairs images with text, and about her advice for multidisciplinary artists looking to publish.

CF: How did you first become interested in Walter Benjamin’s work? What drew you to him and his writings?

FC: In grad school, I took a course called “Melancholy and the Literary Uses of Sadness.” What a cruel joke—to gather a dozen depressed writers into the same room every week throughout the winter to discuss a long list of dark, twisted, lonely, morose texts. Our professor, Jeff Porter, managed to put together a refreshingly diverse and captivating list of authors—W.G. Sebald, Marguerite Duras, Mary Shelley, Baudelaire—but the piece that called to me the most was an excerpt of Walter Benjamin’s unfinished magnum opus, The Arcades Project. Looking back now, I’m not even certain if Benjamin was on the official reading list. He may have come up spontaneously during a discussion about the “flâneur,” or the one who wanders aimlessly through a city observing the follies of man. Outside, within. Apart, a part. This concept resonated with me, as I’ve always been inclined towards ethnographic and auto-ethnographic note-taking—sketching portraits on subways and in airports, writing down snippets of strangers’ conversations. In any case, we were tasked with writing an essay in response to one of the texts, or a theme in the course, and as usual I broke the rules and offered a comic of sorts, a graphic essay, as my final project: an illustrated physiognomy of Benjamin’s writings on collecting, primarily from his chapter “The Collector” in The Arcades Project. I pulled from fragments of his text, adding a few of my own thoughts in an attempt to resurrect Benjamin’s archival spirit.

In the book’s preface, you mention that Benjamin was an avid collector, and that you, too, have kept detailed records of your life through “blueprints for imaginary homes, a daily journal dating back to age eight…and lists of everything from early memories to peculiar names on gravestones.” I love the way you say that collecting is “the non-goal-oriented process of accumulation…” To you, what makes something collectible?

I’m so glad that you asked this question, as I’ve been mulling on this question with greater attention this week: how do certain artists, writers, archivists, curators, and collectors decide what is valuable enough to add to their hoard? I’m currently in an artist residency at the Vermont Studio Center, and our two visiting artists, Colin Chase and Odili Odita, both spoke about the importance of the personal archive. An example: Colin Chase builds composite sculptures of everyday materials (bicycle seats and coffee grinders), paired with raw materials (wood, metal) and sacred objects (adornments, icons.) I’m now starting to think of a collection as a type of vocabulary, which is defined by and sculpted by one’s life experience: region, history, culture, research, source material, and so on. For example, my own archive includes a large number of drawings of flora and fauna since many of my family members are botanists and biologists, and I’ve been conditioned to appreciate and gather scientific imagery. The artist in my neighboring studio is more drawn to global symbology: mandalas, spiritual icons, universal representations of the divine mother, and so on. I’m a bit worried that my current collection is entering the realm of kitsch: miniatures! Oh no! As I write this, I’m staring at three objects I have on my desk: a tiny silver apple pie, a miniature hammer, and a little black dog figure. I’m trying to balance this out with enormous art books so that I don’t turn into a paperweight hoarder.

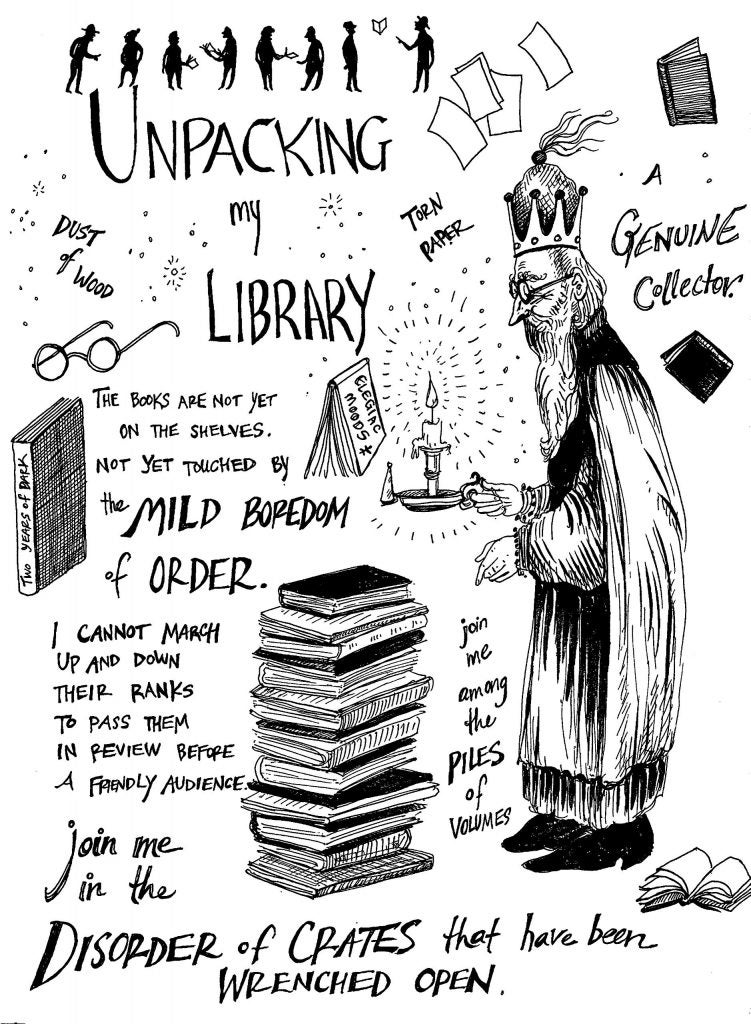

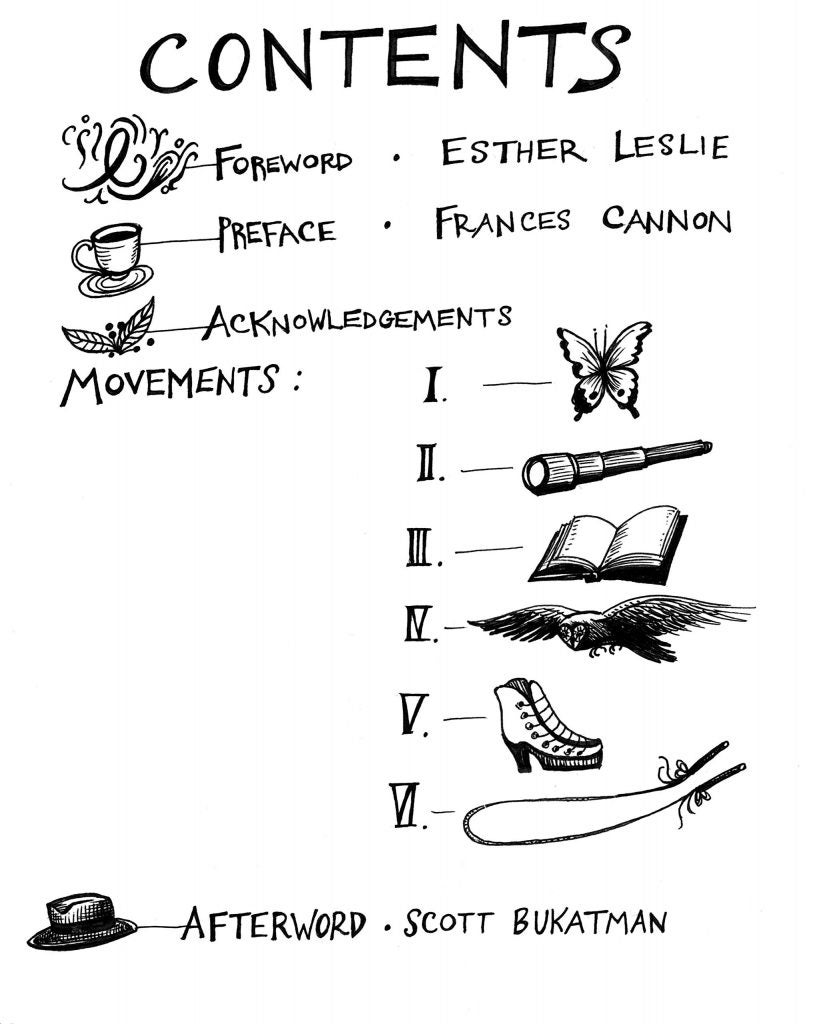

The book is divided into six thematic categories that take a look at the many interests and projects of Walter Benjamin: “Artifacts of Youth,” “Fragments of a Critical Eye,” “Unpacking My Library,” “Athenaeum of the Imagination,” “A Stroll Through the Arcades,” and “A Collection of Dreams and Stories.” Did you have a favorite section to research and develop?

I’m always the most engaged by whimsy and experimentation, so I lingered with greater interest in Benjamin’s The Storyteller, and his various musings, lists, dreams, and short fiction. For that reason, “A Collection of Dreams and Stories” and “Athenaeum of the Imagination” were my favorite chapters to create.

You’ve published several graphic essays in The Iowa Review, The Rumpus, and elsewhere. How does creating an essay with graphics compare to crafting a strictly written essay? Do you find that your process is similar or do they stem from wildly different creative beginnings?

I wish I had a clear answer, but I’m still trying to work this out in my own practice, and my graphic writing is always morphing, shifting, and stuttering. My piece in The Rumpus, “Rooftops of My Youth,” was a pure delight—I sketched out a chronological story of my juvenile delinquent past, and the essay gave me a chance to try my hand at architectural drawings, since the story is about climbing buildings. I would call that piece a comic or a graphic story, since the drawings and story are truly integrated and rely on each other to tell a story. My pieces in The Iowa Review differ a bit: “The Collector” was the seed of this Walter Benjamin book, in that it was my first graphic response to Benjamin’s work. My MIT Press editor and I decided not to include this essay in Walter Benjamin Reimagined because the visual styles are so different, and because “The Collector” is more fragmented and obscure. To contrast with this piece, I wrote an illustrated interview for The Iowa Review which is a fairly straightforward pairing of text and image. The drawings are more complementary additions than essential narrative elements.

Sometimes the visuals are direct representations of a word (such as a picture of a hair dryer next to the word “hair dryer”). Other times, the text is not visualized literally. For example, I’m thinking of page 80. The text reads: “Modern man can be touched by a pale shadow… on southern moonlit nights in which he feels, alive within himself, mimetic forces that he had thought long since dead.” The image we see is unexpected: a ferret balancing atop a solar eclipse. And then there are the terrific visual puns (i.e. overlapping a compass with a flowering rose to create a botanical compass rose). Can you speak about how you see visuals supporting text in this book, and how you went about choosing your images?

Thank you for noticing these details! I appreciate your close reading to both the text and imagery. This balance between representation and abstraction was a struggle for me, and for my editors, and for my collaborators. I wanted to populate the book with a handful of portraits of Benjamin himself, to honor the true author of the book, and to make it clear to the reader that I am translating someone else’s work. This is tricky to do, since there are a limited number of photographs of Benjamin and his cohort, so I had to expand on this source material with a heavy dose of speculative representation. Then, in other passages, as you’ve mentioned, I purposefully wanted to avoid merely ‘illustrating’ the objects and images in Benjamin’s text, so I drew what felt to me to be the central gesture, spirit, and feeling of the passage. During the editing process, I had a team of very talented designers working to finalize my drawings, but we didn’t always agree on this debate between direct illustration and gestural evocation. I’ll say that we had a few minor disagreements about the cover design, title page, table of contents, and chapter headings—they wanted, I think, to guide the reader with more recognizable signposts of meaning, and I wanted to avoid boring the reader with such obvious mirroring of language and art: the word “strolling” paired with a drawing of a shoe, the word “eye” with the drawing of an eyeglass, and so on. We worked it out, and I’m thrilled with the final design.

There’s one section where you talk about Benjamin’s ritual of tying sailing knots. He says, “Knotting is a yoga-like art; maybe the most wonderful of all means of relaxation. One learns it through practice and more practice—not only in the water, but at home, in the calm, in the winter, when one is grieving and troubled. You would not believe how often I have found solutions to questions that burdened me through this.” What is your “knotting”: your hands-on approach to artistic or critical problem-solving?

I always carry a sketchbook around, so that while I’m reading, listening to a lecture, or just sitting on a bench in a quiet park, I can work my ideas out through a drawing. I find this just as meditative as Benjamin’s “knotting,” and it also seems to enhance my understanding of anything I’m thinking or listening to. For example, if I’m attending a seminar, I’m not ignoring the speaker by escaping into a drawing, rather drawing helps me understand the information I’m taking in.

In addition to being a writer and an artist, you also call yourself “a teacher, a cook, and an adventurer.” How do graphics and words collide in other areas of your life, and how do these other identities inspire your art?

I’ll say that art is my calling, while teaching is my vocation, and cooking and adventuring are my hobbies and distractions. I used to work all sorts of part-time jobs in the food industry (baker, line cook, barista, chocolatier, etc.), so a few of my websites and business cards still offer “cook” as one of my marketable skills, but I only cook for fun these days.

I’ve been writing and drawing since I was a wee sprite, and I see those as my skills and pleasures. About teaching: I come from a long line of teachers. My paternal grandmother taught literature and creative writing, and she has served as my mentor and muse since I was just old enough to grasp a pencil. My paternal grandfather, both of my maternal grandparents, two of my uncles, and my mother are also tenured professors, and they have encouraged me to carry on this family mission. Ironically, I rejected the idea of becoming a teacher until grad school. At Iowa, I was awarded a scholarship which paid for my MFA if I taught part-time for three years. They offered a few teacher training seminars, and then set me loose to craft my own courses. Lo and behold, I love teaching! As an adjunct professor, the work is hard and often thankless, but it’s mostly rewarding.

You’ve mentioned to me before that you were grateful that MIT Press believed in the artfulness of this project, and met your book on its own terms. Do you have any advice for multidisciplinary artists looking to find a place to publish their hybrid work?

I feel extremely lucky that my editor found some glint of promise in my original half-formed proposal. It’s very unconventional, even discouraged, to send this type of work-in-progress to an academic press. This makes it a bit hard for me to offer advice, since I still pinch myself with disbelief that the project even made it through the publishing process. A book!? I will say that all of the clichés are true: it took a lot of patience, persistence, and faith in my own idea to make this book. I waited about a year to hear back from the many publishers to whom I sent the original proposal, and then out of the blue, MIT Press responded with interest. Even then, their interest was tenuous, and I had to prove to them that I was capable, qualified, timely, reliable, and rigorous. Hard work! To answer your question about hybrid work, specifically—although this type of experimental artmaking has broad appeal, the portals for publication are still limited. My approach has been to attend all of the book fairs, conferences, workshops, and bookstores that I come across in order to gather information about the possibilities in publishing. I know the type of work that I want to create, but I don’t always know who is interested in helping these projects manifest, so I linger in the graphic literature section of my local bookstore, wander around the bookfair at the AWP conference asking questions, and write to the publishers who make the most beautifully strange books.

Frances Cannon’s book, Walter Benjamin Reimagined: A Graphic Translation of Poetry, Prose, Aphorisms, & Dreams, is published by MIT Press. Find out more about Frances here: https://frankyfrancescannon.com.