Professor James Winn, who taught in the University of Michigan’s English Department from 1983-1998, passed away yesterday. MQR Editor Emeritus Laurence Goldstein remembers James as “a complex, provocative figure and a brilliant conversationalist,” and describes his essay, “The Beatles as Artists,” as a “standard reference work for anyone writing about popular culture and the recent history of musical forms.” This essay by James A. Winn appeared in Michigan Quarterly Review’s Winter 1984 issue.

The stark white graphics on the television screen were terrible in both their symmetry and their finality: John Lennon: 1940-1980. If you had thought of him as permanently twenty-five, the knowledge that Lennon had reached age forty became a part of the larger, more horrifying news that he was dead. For even in separation and disarray, the Beatles served several generations as symbols on which to hang fantasies, aspirations, and not-yet formed identities. And as they came to realize, first from the physically dangerous way their young fans pelted them with jelly beans and grabbed at their clothing, then from the grinding daily impossibility of achieving privacy, their status as symbols was a heavy burden indeed. Typically, it was John who found a way of expressing their plight, with a metaphor many found scandalous; in a song complaining about the way the press hounded him on his honeymoon (“The Ballad of John and Yoko,” 1969), he predicted with wry and eerie accuracy the final bloody cost of his notoriety:

Christ! You know it ain’t easy,

you know how hard it can be.

The way things are going

they’re going to crucify me.

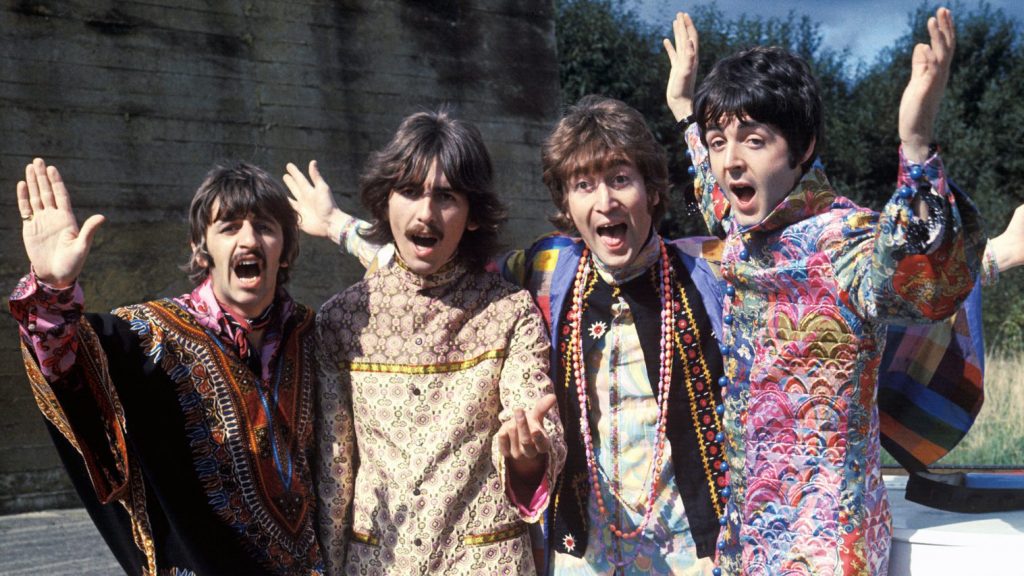

Predictably, the first eulogies in the press concentrated on the public aspects of Lennon’s career: the mass hysteria called Beatlemania, the admissions of drug use, the flirtation with Eastern religions, the naive but touching billboard campaign for world peace. But I shall be arguing here that the lasting accomplishment of Lennon and his mates, their emergence as self-consciously artistic makers of songs, was itself a response to and attempted escape from the burdens of public notoriety. The Beatles gave their last public concert on 29 August 1966; in that same month, they issued the ironically-titled Revolver, an album that signaled a new introspection and a greater willingness to test and tease the hearer. Freed from the exhausting and demeaning business of touring, they were able to sustain their growing complexity and creativity for four highly productive years, during which they produced Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967), Magical Mystery Tour (1967), the double album called The Beatles(1968), Abbey Road (1969), and Let It Be (1970)–albums that expanded and apparently exhausted the possibilities of the rock song.

This fruitful withdrawal from public performance necessarily followed at least a decade of frequent performance; indeed, in the early years of the group’s development, the Beatles sought every opportunity to perform, presumably because they craved money, success, and notoriety–not because they wished to make an artistic statement. John’s wacky and deliberately inaccurate account of their early history, written in 1961, dismisses the motives for their trip to Hamburg as purely monetary: “And then a man with a beard cut off said–will you go to Germany and play mighty rock for the peasants for money? And we said we would play mighty anything for money.” One thinks of Dr. Johnson’s equally proud and practical statements: “Sir, I could write a preface upon a broomstick” or (even closer) “No man but a blockhead ever wrote, except for money.” In both cases, the claim to be motivated by money is at once a declaration of professional pride and a rejection of more Romantic notions of the reasons for creativity. By declaring that one plays concerts or writes prefaces for money, one emphasizes the work involved and casts doubt on the notion that the making of music or literature is a mysterious, metaphysical, quasi-religious calling. By 1968, when “interpretations” of Beatleslyrics were a constant topic of journalism and party conversation, John would debunk the idea of his work as “art” in an even more savage way: “It’s nice when people like it, but when they start ‘appreciating’ it, getting great deep things out of it, making a thing of it, then it’s a lot of shit. It proves what we’ve always thought about most sorts of so-called art. It’s all a lot of shit. It is depressing to realize we were right in what we always thought, all those years ago. Beethoven is a con, just like we are now. He was just knocking out a bit of work, that was all.” For the young Beatles, playing concerts was basically “knocking out a bit of work,” and getting paid meant being able to keep playing, avoiding the duller jobs as deliverymen and factory workers they had briefly held as teenagers. Thus money, as a way to escape the grim Liverpool life of their parents, was a motive they could acknowledge; the notion of making “so-called art,” by contrast, was a ludicrous idea they actively rejected.

Fame fell somewhere in between. According to George Harrison, “we used to send up the idea of getting to the top. When things were a real drag and nothing happening, we used to go through this routine: John would shout, ‘Where are we going, fellas?’ We’d shout back, ‘To the Top, Johnny!’ Then he would shout, ‘What Top?’ ‘To the Toppermost of the Poppermost, Johnny!”‘ But was this routine a “send-up,” a completely ironic gesture of disdain, or was it a therapeutic way of pretending, as record company after record company turned them down, that getting to the top didn’t matter, and thus ultimately a ritual of morale-boosting? If, as I suspect, the young Beatles desperately wanted to achieve fame, but had a concurrent need to pretend to disdain it, would it not be possible to extend that argument to cover their attitude toward “so-called art” as well? To be sure, they did not want to be thought of as pale aesthetes; John’s remarks about Beethoven make that clear enough. But it was the same John Lennon who described his song “Because” (1969) as “the Moonlight Sonata backwards,” and the introduction to that song does strongly suggest the harmonic motion of Beethoven’s piece. So despite John’s warnings against commentary couched in artistic language, and despite what must always have been their own powerful ambivalence about their status as “artists,” the Beatles‘ tireless work at the making and recording of songs after their withdrawal from public performance was ultimately motivated by a quite subtle and impressive aesthetic sense, and by a driving need to create that they shared with many poets and composers. As John himself once said, “I can’t retire. I’ve got these bloody songs to write.”…

_________________________________________________________________________

Read more of James A. Winn’s essay on the Beatles here, in our Archives.