Kathleen Rooney is gracious in her interaction with others. When I first met her, she immediately drew me in by sharing the details of her stroll that day around my town of Columbia, Missouri before her weekend’s engagement at the 2018 Unbound Book Festival. If you follow her online, you will get to see photos of such walks where her artistic shots denaturalize the everyday. As a person, she comes across as thoughtful and self-aware, and though she is clearly always taking in her surroundings, she is also quite sociable. As soon as we began talking at the Friday night reception, I knew I wanted to continue the conversation. Honestly, I’d anticipated it since I’d begun reading Lillian Boxfish Takes a Walk (St. Martin’s Press, 2017), but I was happy in meeting its author that the expectation held.

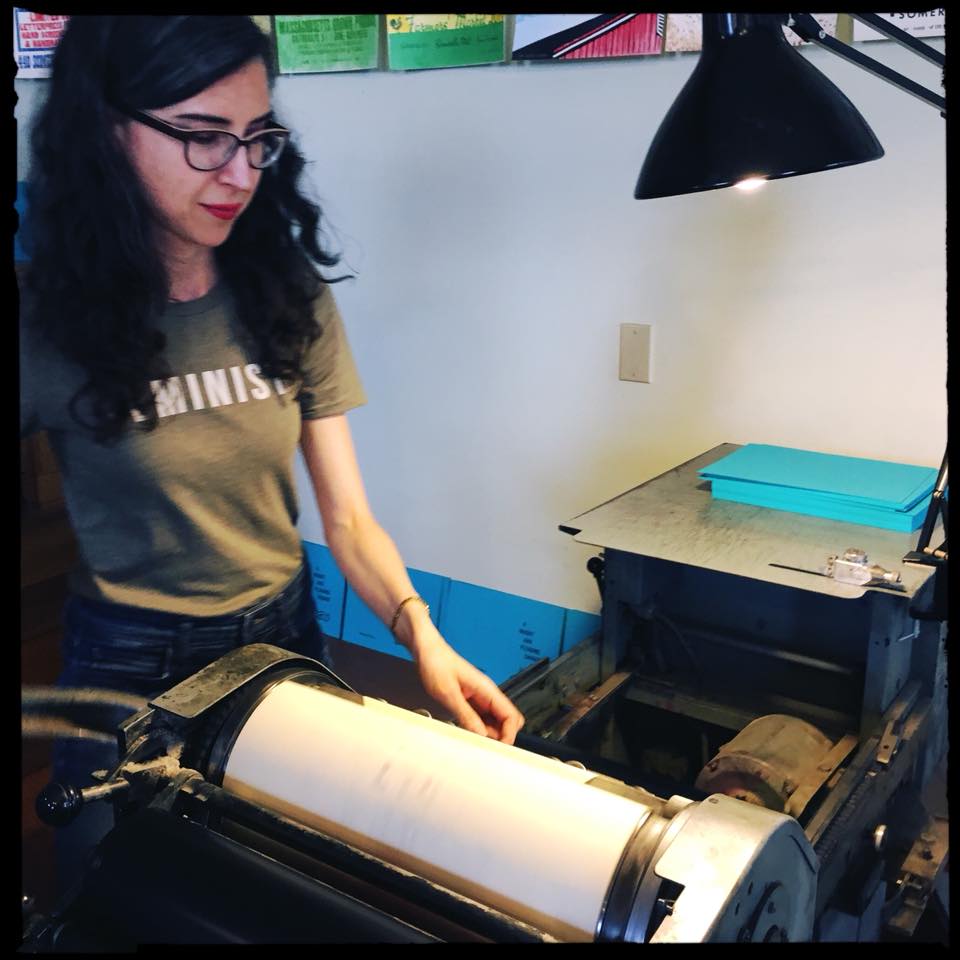

Rooney is the author of nine books across genres and in hybrid genres. She is a founding editor of Rose Metal Press and teaches at DePaul University. Most recently, Rooney wrote The Listening Room: A Novel of Georgette and Loulou Magritte (Spork Press, 2018), which she calls a work of “essayistic prose poems.” She is a co-founder of Poetry While You Wait, where, for just a few dollars, she or one of her cohort will compose a poem just for you on a vintage typewriter.

The plot of Lillian Boxfish Takes a Walk follows a day in the life of a former ad writer for R. H. Macy’s, now in her eighty-fifth year. We move with her on her titular walk through Manhattan in a ten-mile Ulyssean journey in which she traverses the city and the twentieth century on the cusp of 1985. Rooney takes on both the small and the large in this narrative of a place and a life.

In our recent conversation, we talked about the writing life and about how creativity can be embraced more broadly. We also discussed walking, the environment, and a touch of politics. I hope you’ll be as glad to hear from her as I was.

I wanted to start with Lillian Boxfish Takes a Walk, since it has garnered such positive and widespread attention. I know that you were the first non-librarian to delve into Margaret Fishback’s archives (the historical model for Lillian Boxfish), but what other research did you do beyond the person herself? How did you incorporate that research into your fiction?

The archives at the Duke University Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising & Marketing History were indispensable in the sense that without them, I never would have had access to such a wealth of primary documents by and about Margaret Fishback, Lillian’s real-life inspiration. But I had to do a ton of research beyond the week that I spent there in order to build the idea into something that would work as a novel.

The archives at the Duke University Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising & Marketing History were indispensable in the sense that without them, I never would have had access to such a wealth of primary documents by and about Margaret Fishback, Lillian’s real-life inspiration. But I had to do a ton of research beyond the week that I spent there in order to build the idea into something that would work as a novel.

The two main areas I found myself delving into were advertising history and the history of the city of New York itself. Since Margaret (and therefore Lillian) was part of a wave of pre-Mad Men female advertising pioneers whose stories remain too little known, I relied on such books as Advertising Careers for Women, edited by Dorothy Dignam and Blanche Clair and published in 1939, which I learned about by stumbling on Fishback’s own marginalia-laden copy as part of her archive.

And for New York, Luc Sante’s Low Life: Lures and Snares of Old New York was crucial in helping me get past my preconceived ideas of New York’s ups and downs and begin to understand what it was really like over the first decades of the twentieth century, right before and then as Lillian would have been arriving in Manhattan. Newspapers of the eras I was writing about from the 1920s up until the 1980s (particularly reporting on the Bernard Goetz Subway shooting) were key to my being able to understand not just events, but also the tones, language, and attitudes used to discuss the events at the time they were taking place. Also for voice, Jane Jacobs’ The Death and Life of Great American Cities was vital.

Like Lillian Boxfish, I know that you enjoy walking, and when we spoke at Unbound, you told someone in the audience that you prefer city walks to nature walks because the latter are “boring.” Does that mean you’re more interested in people over nature, or is it about visual spaces of the city, since I see you often post photos of your walks?

“Impossible” is the word I should have used instead of “boring.” While I do personally find more that fascinates me in the places where human activity is most visibly evident on the landscape, the very idea of “nature” itself strikes me as sanctimonious — precious and false. In his book Ecology Without Nature: Rethinking Environmental Aesthetics, Timothy Morton makes the case that the biggest impediment to environmental thinking is the notion of nature itself. And I tend to agree: there is no “nature” — some artificially demarcated entity separate from humans — and there never has been, and climate change is forcing us to realize this more and more.

When you throw something away, there is no away; we can’t get outside of our own impact anymore and we probably never could. You could take a “nature walk” on a deserted beach and gaze at the ocean, but that doesn’t change the fact that the Pacific Garbage Patch is out there. So — as well-intended as they undoubtedly are — nature walks framed explicitly as nature walks leave me cold chiefly because this revered ideal of the pristine and renewing effects of spending time in some kind of bucolic, pastoral setting or the image of pure and untouched topography has always been little more than a comforting fiction.

The intersections and connections between us humans and our environment seem more provocative, and in some sense more honest. It’s all ecology and we can’t pull ourselves beyond it, no matter how much we’d like to think so.

You recently published a book on René Magritte as told by his wife and Pomeranian dogs called The Listening Room: A Novel of Georgette and Loulou Magritte, and you’d previously coedited a collection of Magritte’s writing. What drew you to Magritte?

You recently published a book on René Magritte as told by his wife and Pomeranian dogs called The Listening Room: A Novel of Georgette and Loulou Magritte, and you’d previously coedited a collection of Magritte’s writing. What drew you to Magritte?

Magritte, to me, is kind of a writer’s painter, and by that I mean that his work concerns itself with wit and language, as well as the way the human mind structures and communicates thoughts and meanings through words. The mysterious pleasure of his work derives in large part from how figurative it is, how representational, and how the images suggest wild and engaging narratives without being reducible to a single story.

As a kid growing up in the Western suburbs of Chicago, I was especially drawn to his work at the Art Institute whenever we’d take class field trips there. His painting The Banquet — with the fiery sunset behind the green trees and the sun that is somehow positioned in front of them — really mixed up my mind, as did On the Threshold of Liberty. Even as far back as when I was ten years old, I felt fascinated by how he titled his works; so many other artists’ paintings were called “Untitled” or something extremely boring, and as an aspiring writer myself, I admired the way he put his titles in poetic harmony with his images.

More generally, how do you decide which project is your next piece of writing?

I try to keep a good balance of currency in my idea bank, so to speak; I always have a few long-ish term projects stockpiled for future use. I have the concepts roughly outlined — and I mean really roughly — in documents on my computer so that when I finish one, I can move on to the next one, and so I can also gather (casually at first, then with increasing intensity) materials and notes that will prove helpful when I eventually turn my full attention to them.

I think a lot about Muriel Spark’s Loitering with Intent when I think about how I do this. I normally don’t care for fiction about writers as it can tend to be either very dull or very mystifying, but her novel really captures that constant-search-for-opportunities feeling of working on a novel — how if you just keep your mind open with a certain semi-focused intensity, the world starts to present you with all kinds of details and information that seem tailored specifically to your purpose.

You’re not just involved in the writing side of things; you’re also a founder and editor for Rose Metal Press, which publishes works that fall outside of our basic genre expectations. Why did you dive into that side of the industry?

Shortly after our graduations from the MA and MFA programs in Writing, Literature, and Publishing at Emerson College, Abby Beckel and I co-founded the press in Boston in January of 2006. In observing the literary community, we noticed that many writers were doing brilliant work in what we considered hybrid genres, but that they had limited opportunities to publish that work since few commercial publishers accept such submissions due to concerns over profitability and marketing. Thus, we decided to make the publication and promotion of that kind of work — prose poetry, short short fiction and nonfiction, book-length narrative poems, image and text collaborations, and so on — the focus and mission of Rose Metal Press.

We’ve been at it for twelve years and counting and are continually delighted at the kinds of projects the press gives us a chance to work on. One forthcoming book about which we are especially excited is Nicole Rivas’s chapbook of flash fiction, A Bright and Pleading Dagger, about which Rigoberto Gonzalez says: “For their thought-provoking denouements and skillful use of compression, the stories of Nicole Rivas beg comparisons to the celebrated stories of the surrealist painter Leonora Carrington. For their arresting strangeness, readers of Latin American literature will recall the stories of Clarice Lispector. But for their edginess and fearless wit, a more contemporary sister is Carmen Maria Machado. Yet Rivas will thrive on her own terms. A Bright and Pleading Dagger is truly a compelling and unforgettable journey into the dark but poignant experiences of women.”

Another is Maria Romasco Moore’s Ghostographs: An Album, about which Carmen Maria Machado says: “Each of these stories is its own ghost: startling, uncanny, gone. Each one rattles its chains, smiles its terrible smile, gestures toward the others. I feel like this book was written, specifically, for me: the me that loves vintage photographs, formal constraints, hauntings, ephemera, poetry; the me that loves campfire stories; the me that’s still a little scared of the dark.”

How does your teaching relate to your writing process?

I love teaching! It’s so much fun and it’s an activity that never fails to sharpen my own skills as a reader, writer, and thinker. When I teach, I’m perpetually vigilant for ways to explain whatever it is that I’m talking about with great precision and subtlety, but also in a variety of modes that could connect with a variety of different student writers. Being able to explain something with nuance is a surefire way to make sure you’re doing whatever it is as well as possible yourself. DePaul University, where I teach, gives professors a great deal of freedom in determining their reading lists and creating their syllabi, so I’m fortunate in that my classes get to consist of things about which I’m extremely enthusiastic. I feel lucky to get to walk into a classroom and talk to groups of bright, engaged, curious people about texts I admire and think they’ll get a lot out of.

For instance, this past Spring, I got to teach English 101: Introduction to Literature, and I was able to theme it as “Ladies’” Night, and to assign work exclusively by women and non-binary writers, including Elisa Gabbert, Mary Gaitskill, Juliana Huxtable, Ijeoma Oluo, Valeria Luiselli, Morgan Parker, Rose Tremain, and more.

You’re working on issues of writing from so many angles. Did you ever consider being anything other than a creative type?

Yes! As a kid and a teen, I thought that I stood a chance at being America’s first woman President, not having fully realized the extent to which systemic sexism and institutionalized misogyny, not to mention survival-of-the-richest hyper-capitalism, might make that an unwinnable goal. I studied political science as an undergraduate at George Washington University. I grew up in the intensely Republican DuPage County in Illinois and began working on (doomed) Democratic campaigns before I could even vote. And for many years I worked in the Chicago office of U. S. Senator Dick Durbin.

I’ve always been someone who has wanted to “be the change” and “make a positive difference.” I put those in quotes not to mock them as clichés, but because they are ideas that used to mean — and still do mean — a lot. America has always been disappointing, has always been unjust, has always fallen despicably short of the starry ideals expressed in the Constitution. But despair and inaction can’t be the answer, or at least they can’t be for me.

Even though now I guess I am a “creative type,” I’m hesitant to say that politics and activism and a whole host of other pursuits aren’t also creative, or that “creative types” need to just stay in their creative lanes and that’s it. As citizens, we all have to reach out and try to be compassionate and kind, and to make sure we are working for a better existence for everybody all the time.

You’ve lived in a lot of places. You were born in West Virginia, raised in Nebraska, Louisiana, and Illinois, and you completed your education up and down the East Coast. Now that you are situated in Chicago, how has the city and the region influenced your sense of writing and perhaps a sense of a creative community?

Chicago is the city of my heart. I adore cities of all kinds around the globe from Mexico City to Kansas City, from Los Angeles to Tokyo, and on and on — being in them, walking around them, meeting the people who live there. But Chicago is the place that feels like home and the one I hope I never have to permanently leave. Part of that is some kind of ineffable connection that I can’t fully describe — a psychogeographic texture that feels like a fit for me. But beyond that, the people in general and the literary / artistic / creative / progressive communities specifically are brilliant, fun, and welcoming.

Chicago is also unpretentious af. There’s virtually zero tolerance for posturing or bullshit here and a real sense that everyone has something worth contributing, and nobody has any business presuming they are superior to anyone else.

What are you working on now? Does it feel like a continuation of any of these other projects or is this a new path?

I’m working on a World War I novel about a heroic soldier and a heroic messenger pigeon. Both figures are based on actual people, and the book alternates between their respective first-person narrations. The book feels like both a continuation of the work I began in Lillian in the sense that I’m bringing a once-famous but now long-forgotten historical figure to life through fiction, and a continuation of the work I did in The Listening Room, with its dog-perspective, in that I’m once again playing around with the voice of a non-human being. Stay tuned!

Find out more about Rooney’s work at kathleenrooney.com, or follow her on Twitter @KathleenMRooney. For information about Rose Metal Press, visit rosemetalpress.com.

Inset photos courtesy of Kathleen Rooney.

Abigail G. H. Manzella is the author of Migrating Fictions: Gender, Race, and Citizenship in U.S. Internal Displacements (Ohio State University Press, 2018). Her writing has also appeared in publications such as The Rumpus, Kenyon Review, PopMatters, Ms., and Bust. Find out more at abbymanzella.weebly.com or follow her on Facebook @AbbyManzellaAuthor or on Twitter @AbbyManzella.