“In Search of Man: Experiments in Primate Communication,” nonfiction by Francine “Penny” Patterson, appeared in the Winter 1980 issue of MQR.

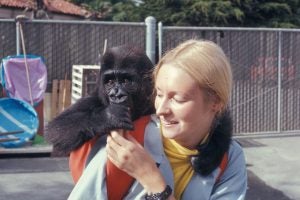

Patterson is an American animal psychologist best known for her sign language work with Koko the Gorilla. Patterson currently serves as the President and Research Director of The Gorilla Foundation.

A phenomenon which once existed only in the province of myths and children’s stories has become a reality. We can now communicate with other intelligent life forms. While some have been looking to the stars to find such creatures, we have discovered these intelligent beings right here on earth. That we haven’t spoken with them sooner has been our fault, not theirs. Now that we can speak with them, what are they telling us about themselves, about ourselves?

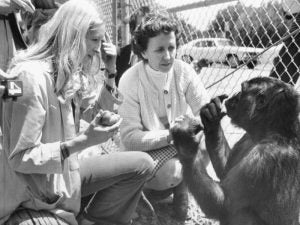

What I am referring to, of course, is the recent research with the great apes. During the past ten years the behavioral sciences have slowly become acclimated to reports that chimpanzees have mastered the basics of symbolic communication in a visual mode. Assimilation of this new literature has been slow because decades of unsuccessful attempts to teach apes spoken language had produced a general skepticism. The current consensus appears to be that apes have at least a rudimentary capacity for symbolic representation and communication, but that important differences exist between this capacity and our own. For Colin Cherry, noted scholar on human communication, the differences between humans and animals who use sign languages are the following:

- Only humans can speak about feelings with intent–only a human knows he has a feeling.

- A child can generate sentences of unlimited kinds and can invent his own private words and use them grammatically; that is, he begins to use language creatively.

- Humans can use language imaginatively to refer to non-existents and to abstracts.

In this essay I will attempt to present evidence, in case study form, to show that a gorilla has spontaneously displayed uninstructed abilities which satisfy each of these criteria.

Gorillas are tragically misunderstood animals. In fact shy, placid and unaggressive, they are conceived to be ferocious man-killers. In a recent poll of British schoolchildren, gorillas ranked with rats and spiders among the most hated animals. Pioneering primatologists reported that the gorilla was difficult to work with because of its low level of motivation and negativistic disposition. Later researchers did not alter this reputation very much; one team reported that there was little question that the gorilla’s abilities for conceptualization and abstraction were inferior to those of the chimpanzees.

The generally accepted belief, consonant with these views, that the chimpanzee is our closest living relative, was bolstered by biochemical evidence from analyses of homologous proteins and nucleic acids. However, recent comparative studies of human and ape chromosomes indicate that man’s closest genetic relative may be the gorilla, followed by the chimpanzee and the orangutan. We would expect that the primate most closely related to us might also possess cognitive capacities most closely approximating man’s. I hoped to discover by means of an extended research project just how close the similarities might be, and where the differences lay. Such an endeavor could bring us nearer to an answer to the question, “What makes man human?”

Lead image: Scene from “Koko: The Gorilla Who Talks.” 2016. BBC.