I first met Laura Esther Wolfson in 2016 when we were both co-producers of AmpLit Fest in New York City. Struck by her attention to the nuance of foreign and familiar languages, not to mention her resilience as a so-called “emerging writer” despite her work being widely published and anthologized for decades, I had the distinct pleasure to interview her at her Upper West Side apartment early one Sunday morning.

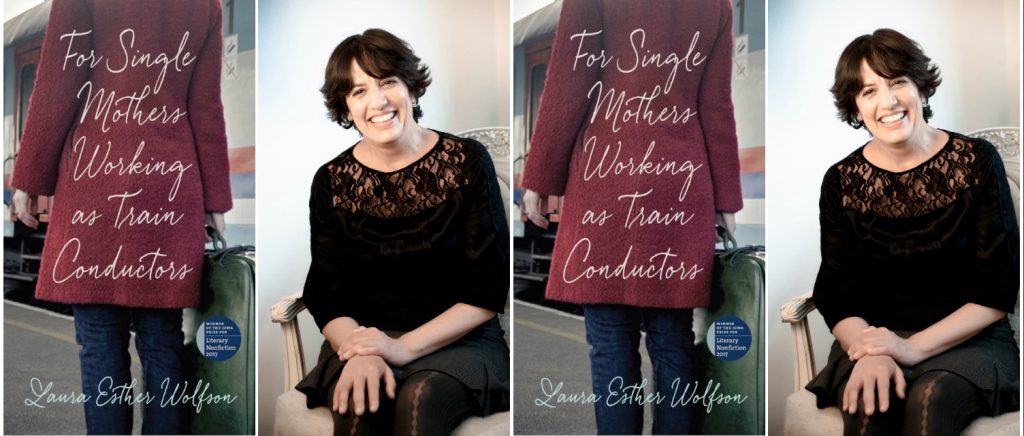

Her debut essay collection is For Single Mothers Working as Train Conductors (University of Iowa Press, 2018), winner of the 2017 Iowa Prize for Nonfiction. Whether exploring the delicate work of examining self and the world post-divorce, the tightrope walk between language and place, the onset of chronic illness, or the deep longing for children, Wolfson’s collection spans the breadth of the human heart and the heights of intellect. For Single Mothers is a book that commands attention.

Wolfson is currently at work on her next book, Super-Pricey Royal Blue French Lace Bra. Her prose has been honored with the 2017 Notting Hill Essay Prize, published in leading literary venues on both sides of the Atlantic, and cited in The Best American Essays. She served for many years as the interpreter for Russian-speaking authors at the PEN World Voices Festival and as a PEN Prison Writing Mentor. She is a Fellow of the MacDowell Colony (2018) and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts (2017). Wolfson holds an MFA from the New School and lives in New York City.

How did you choose the title For Single Mothers Working As Train Conductors?

My first husband, who was from the USSR, said that if we had a child, we would have to put him or her in 24-hour daycare. I had never heard of such an institution, and I was baffled. Why would anyone plan to have a child and then choose not to raise it?

Years later, I asked a Russian friend if there were indeed 24-hour daycare centers in her home country. She told me, after some thought, that there were, for single mothers working as train conductors who had no family nearby to care for their children while they were traveling for work. (Other Russians have since told me that these institutions were/are not specifically for single mothers working as train conductors, but for parents in any occupation involving long or difficult shifts.) I put the title piece first because it introduces many of the themes returned to later in the book: marriage, longing for a child, Russia and its recent history, my work as a Russian linguist.

You’ve said that if you could write one good essay per year then you’d be happy. For Single Mothers won the 2017 Iowa Prize for Nonfiction and it’s your debut collection — what was the journey like to get here?

You’ve said that if you could write one good essay per year then you’d be happy. For Single Mothers won the 2017 Iowa Prize for Nonfiction and it’s your debut collection — what was the journey like to get here?

This book, which I wrote over the course of fourteen years, contains thirteen essays. There were a few other pieces that didn’t go in. I didn’t write it as a book — all of the pieces were standalone. When I revised it for publication last year, a large part of the process involved weaving the parts more tightly together. It astonishes me that some of the critics call it a book-length essay or a memoir. To me it’s obviously a collection.

How did you sustain your writing practice all that time?

I wrote slowly on the weekends while working full-time. My second husband encouraged me. (We’re no longer together.) He’s French Canadian, and didn’t speak English when we met. I used to read my work to him even before he understood much. He would comment on the rhythm and the speed, because that was what he could grasp. He believed strongly in the value of writing.

Did you finish any other books before For Single Mothers?

I also wrote a failed novel during this time, about my grandfather. It was rejected by some eighty literary agents, many of whom initially expressed interest, but ultimately didn’t want to represent it. I was getting anxious at being well past forty, without even one published book to my name. Someone suggested that I assemble the essays into something coherent and shop them around as a collection. First I went the literary agent route, and when that didn’t work, I sent it to competitions. But while I was writing the separate parts, I didn’t conceive of it as a book.

Very often I find that an author’s first manuscript isn’t published initially — it’s shelved or the timing isn’t right until years later. It’s encouraging to see that you didn’t just sit down and write this manuscript one day — it was a fourteen-year journey. How many books have you written total?

I have three unpublished manuscripts — one written in my 20s, one in my 30s, and one in my 40s. I started For Single Mothers in my late 30s and continued working on it into my early 50s, so there was some temporal overlap with other things I was writing. The other manuscript that I wrote in my 30s was a series of vignettes that I now think was a precursor to this book. I think some of the material in there is related. It also contains a lot of writing about language. Sometimes when I go through old papers, I find that I’ve written the same sentence twice or even three times, years apart, indicating that my obsessions have remained constant. Or perhaps that I have not progressed.

How many languages do you speak? I know this is a layered question because one could be fluent or intermediate — one could read in a language, but not hold a conversation in it.

It’s good to recognize that, because what does it mean to ‘know’ a language? Every language is seemingly infinite—there are always more lexical items, more idioms, more literature. I speak Russian and French fluently, and Spanish and Yiddish badly. Plus, of course, English, my mother tongue.

During my job as a translator at the United Nations, I learned Spanish because I was expected to translate documents from Spanish. My translations from Spanish were always vetted by senior colleagues who knew the language well. I don’t always tell people that I translated from Spanish, because although I read it proficiently, my spoken Spanish is halting.

You write about translating or interpreting state banquets at the Kremlin, mafia trials, forgotten literary masterpieces, KGB files, and so much more. What’s one job that stands out to you?

I interpreted for Hillary Rodham Clinton on a trip she made to Moscow as First Lady. She was extremely tactful, diplomatic, and kind to everyone she met. She spent much of her time there with the wives of the prime minister and president of Russia, who were lifelong political wives. She didn’t flaunt her credentials whatsoever. She ooh’d and aah’d over photographs of their grandchildren.

At a state banquet in the Kremlin, she was seated next to President Yeltsin. The waiters brought out the first course, and Yeltsin said, “Oh, yum.” She said, “What is it?” I was sitting between them. He said, “It’s lips.” I broke out of my interpreter mode and I said, lips?! He said, “Yes, elk/moose lips.” Russian has one for both ‘moose’ and ‘elk.’ I had no way of knowing which one it was, so I took a flying leap (working as an interpreter involves some of those) and landed on ‘moose.’ Later, a lexicographer friend who had authored a leading Russian-English dictionary told me that the word ‘moose’ is used exclusively in North America, so my rendering was not idiomatically correct. Interpreter error, oops!

Yeltsin kind of stood over her and made sure she ate it. She protested, saying, “Oh, I worked in Alaska one summer when I was in college, and I saw moose there. Such nice animals.”

Do you think translating literature is inherently a political act?

It depends on what you’re translating. I suppose translation is inherently political, not only because it may lift things—subjects, authors, books—from oblivion, things that the powers that be might prefer to let lie, but also because translation bridges cultures.

In the Trump era, many people have spoken about the inherent subversiveness of reading and writing. I grasp this, yet some part of me thinks that we (writers and readers, as well as translators, who are the closest readers of all, and whose work partakes of both reading and writing) are simply trying to justify doing what we were doing before, and no more — as if sitting with a book open in front of you constitutes adequate resistance in the current climate.

What’s one book you found gratifying to translate?

I am proud to have translated Stalin’s Secret Pogrom (Yale University Press, 2001), about the execution, in the course of a single night in 1952, of many or most of the leading Yiddish authors in the Soviet Union. This atrocity is referred to as The Night of the Murdered Poets (although many of those killed were in fact prose writers). It was literary genocide. I know of no other case in which the leading writers in a given language were lined up and shot. Few people are aware of this event, particularly here in the West. I thought it was important for it to be more widely known.

I read recently that the Anti-Defamation League released findings from a massive global poll stating only fifty-four percent of people surveyed have ever heard of the Holocaust, and thirty-two percent believe the event was greatly exaggerated or a myth. Why did you choose to write about WWII so strikingly in your book?

Those are appalling numbers.

I didn’t plan to write about the Shoah. I went to Lithuania in 2007 to study Yiddish, which I had been studying already in New York, and because I was struggling to write a novel about my grandfather, who was from Lithuania. Although I am a Russianist, I was somehow unaware until that trip of how thoroughly the Germans had occupied the Baltic States (Lithuania, Estonia, and Latvia), which later on, following World War II, were annexed to the Soviet Union. The Germans rounded up and killed upwards of ninety percent of the Jews in that region. If my grandparents had not left in the early 20th century, they would no doubt have been rounded up too, and I would not be here speaking with you today, in fact I would not have been born.

During that sojourn in Lithuania, which lasted about a month, I heard much discussion of the Holocaust, in Yiddish classes and on field trips. The Jewish community of Lithuania had been virtually wiped out. We visited villages where just one Jew remained, generally someone who had been out of town when the Germans swept in, or been hidden in an attic or a barn by some kind gentile neighbor. I ended up writing about it because of all that I heard there. I met Faina, as I call her in the book, and she told me her story.

Reading about Faina in “The Book of Disaster,” it felt like fate compelled you to tell her family’s Holocaust story. So many fascinating figures and their histories are woven throughout this collection that I began to wonder if it’s because you were an interpreter that the voices around you infused your own experience.

Oh, that’s interesting. It’s true that as an interpreter you get used to listening and then repeating what other people say. (You say it in another language, of course, that’s what interpreters do, but to a bilingual or multilingual person, it can feel like mere repetition.) It’s limiting to concentrate exclusively on yourself when writing a personal narrative. Lives overlap, so if you write about yourself, you will end up writing about other people. Faina, in particular, clearly wanted her story told.

In “The Bagels in the Snowflake,” bread serves as a mystical connection to Judaism. What’s your relationship to Judaism now?

I became interested in Judaism in my late twenties. I was reading about Passover (which we never celebrated when I was growing up) and only then did I learn that the youngest person at the Seder traditionally asks four questions about the meaning of Passover. The ancient rabbis decided to organize the ceremony that way, reasoning that the youngest person present would pass the story down furthest into the future, preserving it longer.

This stopped me cold, because it was in the generation before mine that this tradition was lost — it continued down for millennia and then stopped abruptly with my parents and grandparents. My mother was the youngest of 30 first cousins. Year after year she had to perform that part of the Seder before a throng of older relatives. She was shy. She hated the attention, and vowed that she would never put any child of hers through that. She wanted to protect us. She wasn’t thinking about tradition. Because of that lacuna in my upbringing (and perhaps because I was that youngest child, the one who was supposed to play a key role at Passover, but never did), I started reading voraciously about Judaism.

I never became a truly observant Jew. You have to know the Hebrew texts, and it’s hard to take that up when you’re an adult, unless you devote yourself to it full-time. Those holy texts are the heart of Judaism. To me, cooking Jewish dishes, let’s say, or taking pride in the Jewish moguls of Hollywood—those things are peripheral.

The notion of a secular Jew is a paradoxical one. I think ‘secular Jew’ is a euphemism applied to someone who’s assimilating, and whose children or grandchildren will celebrate Christmas, retaining only a vague awareness of their Jewish ancestry. But I was raised a secular Jew, and I can overcome it only to a certain extent.

The year after you were diagnosed with the lung disease Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM), you entered the New School MFA program. Did you feel compelled to write about LAM to let other writers know this is just another part of your life?

My current work in progress, Super-Pricey Royal Blue French Lace Bra (Blue Bra, for short), was just rejected by a literary agent who said she didn’t like medical topics — although the book is about many other things as well. Not to mention that health problems are such a big part of life. I write about many things. Illness is just one thread.

I got into a Lyft car the other night, heading downtown to participate in a literary reading. The driver asked about the oxygen machine I pull around with me, and about the tube in my nose. I explained that I have lung disease and severe shortness of breath. Then he asked, “Are you going home now, or are you going to the doctor?” I said, “Neither. I’m a writer. You are taking me now to give a public reading of my work.”

When I read your work it’s deceptively spare. You put in an enormous amount of hard work so that it reads effortlessly — a noun or an adjective shivers like a struck bell in a sentence. Who are your influences or who do you love to read?

W. G. Sebald is not well-known, but those who do know him consider him one of the greats of the late twentieth century. I learned languages in order to read certain works of literature in the original, but ironically, I cannot read Sebald in the original, as I don’t know German—which gives me a rest, actually. I love Proust, Rebecca West, author of Black Lamb, Grey Falcon, a travelogue about Yugoslavia in the 30s — very stylishly written, and the Russians: Babel, Tolstoy. I love Doris Lessing, who often writes straight realistic fiction, but The Golden Notebook is very innovative. I love a lesser-known work by James Baldwin called No Name in the Street.

What is it about these authors or their style that draws you in?

I love the first-person, autobiographical voice. (That doesn’t cover Tolstoy, but it accounts for just about everyone else on the above list.) Looking back over my reading, starting from when I was very young, I see that I have always loved that voice. Laura Ingalls Wilder, of Little House on the Prairie fame, wrote in the third person. When I realized at eight or nine years old that she was recounting her own life in those books, I was disappointed in her for not using the first person and taking full ownership of her story.

In “Losing the Nobel,” you describe the decision to turn down translation work in order to prioritize writing your own books. You’ve also joked that you’re forging a new genre by writing about projects you didn’t translate. Do you feel the need to choose between the two?

Many writers don’t need to choose between their own work and translation — they do both. Perhaps because translation has been my day job for decades, it feels like a way to procrastinate about my own writing. When I learned that Svetlana Alexievich had won the Nobel Prize, I of course regretted turning down the opportunity to translate her books. Yet I knew deep down, and even not very deep down, that it wasn’t the right project for me.

“Losing the Nobel” is, in part, about the difficulty of writing in obscurity for so long. Those years of obscurity made me think that I longed (or would settle) for some other kind of recognition (as a translator rather than as a writer), when in fact, for me, that would have been a poor substitute. “Losing the Nobel” won the Notting Hill Essay Prize and then was included in the book that won the Iowa Prize. Turning down that translation opportunity not only gave me more time and strength to write, but also led to some unexpected recognition as a writer.

Do you have a new project in the works?

Super-Pricey Royal Blue French Lace Bra is even more personal than For Single Mothers. I’m struggling now with writing about sex in Blue Bra.

When I wrote the title section of For Single Mothers Working as Train Conductors, I was embarrassed to tell about giving away my diaphragm and spermicide to my sister-in-law, who was Soviet and lacked access to reliable birth control. (I was returning to the US a day or two later, so I could easily replace them here.) I included that incident because it was bizarre and very, very sad. For over twenty years, I thought: I have to write about that!

But in Blue Bra, I’m actually writing about … the sex act! Oh, my God! It would be okay, except that I’m the one engaging in the sex act. I even digress and say that this is hard for me to write about; when I was growing up, there was no overlap between sex and language. Sex was never talked about.

Did it give you pause to publish essays about your personal life?

While my writing is autobiographical, I don’t feel beholden to the facts, because I’m using the materials of my life as design elements in a story. The purpose is not to tell people that this is what happened, nor, I hope, will people read my work in order to find out about my life. I want people to read these essays as works of literature, as stories. It feels more real to be working with actual material from my life, but there are points where I embroider a bit, and I don’t always remember where I’ve done that, and then the thing I’ve written becomes more real than whatever actually happened. But Oprah can’t berate me [as she did James Frey, the author of A Million Little Pieces], because I’m very upfront about the fact that my purpose is not to report.

As I’ve said, many different genre designations have been attached to my work, and my feeling is: the more the merrier. I’m delighted every time someone comes up with a new genre designation for whatever this thing is that I do. I envy you poets because no one asks you whether what you’ve written is fact or fiction. But the only way I can write is to use my own life as the point of departure.

Find out more about Wolfson’s projects at lauraestherwolfson.com, or follow her on Twitter @estherlaura.

Find out more about Wolfson’s projects at lauraestherwolfson.com, or follow her on Twitter @estherlaura.

Sarah M. Sala is a poet, educator, and native Michigander. Her debut poetry collection, Devil’s Lake, was a finalist for the 2017 Subito Book Prize, and her poem “Hydrogen” was featured in the “Elements” episode of NPR’s hit show Radiolab in collaboration with Emotive Fruition. She is the founding director of the Office Hours Poetry Workshop and coproduces AmpLit Fest in conjunction with Summer on the Hudson. Visit her at sarahsala.com.