Lawrence Joseph in conversation with Philip Metres excerpted from the Winter 2018 issue of MQR.

Born in Detroit in 1948 and the grandson of Syrian Lebanese immigrants, Lawrence Joseph graduated from the University of Michigan, where he received a major Hopwood Award for poetry, followed by the University of Cambridge and then the University of Michigan Law School. Joseph’s books of poetry — So Where Are We? (2017), Into It (2005), Codes, Precepts, Biases, and Taboos: Poems 1973–1993 (2005), which includes Before Our Eyes (1993), Curriculum Vitae (1988), and Shouting at No One (1983) — published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, have received international acclaim. He is also the author of Lawyerland (1997), also published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, and The Game Changed: Essays and Other Prose (2011), which appears in the University of Michigan Press’s Poets on Poetry series. Among his awards are fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts. He is Tinnelly Professor of Law at St. John’s University School of Law, and lives with his wife, the painter Nancy Van Goethem, in lower Manhattan.

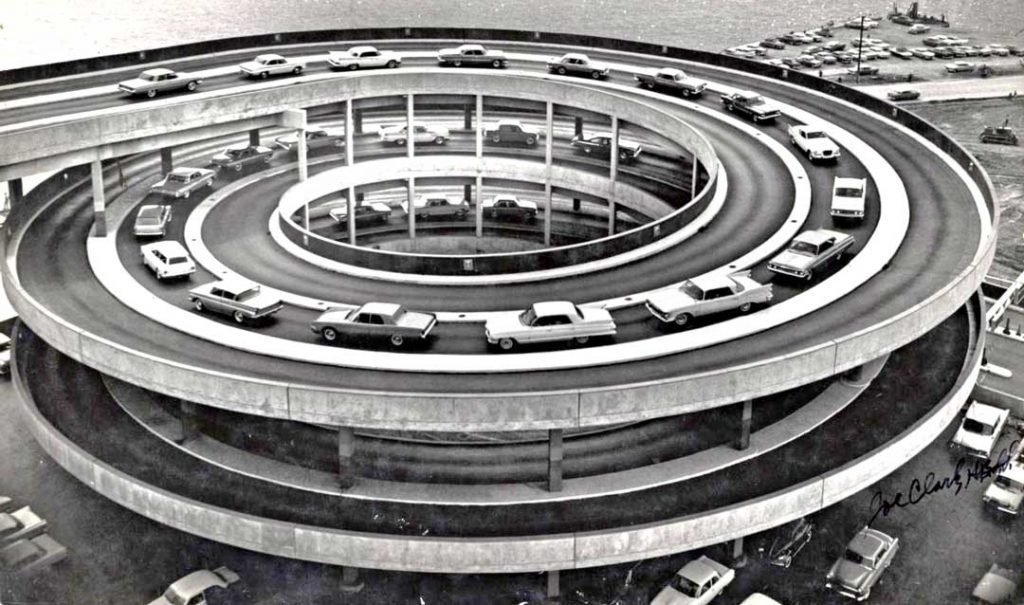

Lawrence Joseph’s poetry emerges from the world of his native Detroit, where, during the 1967 Detroit riots, he witnessed firsthand his father’s burned and looted grocery store. A clear-eyed voice of conscience, Joseph, book by book, has developed poetry of fiercely intelligent, gyring consciousness, tracking the effaced connections between capital and violence — at home and abroad, particularly in the Middle East — while never forgetting the mysterious wonder of being alive. Reading Joseph is like reading a postmodern Jonah walking in Nineveh, whose capacious vision of the implicating networks of economic and military power does not allow him to absolve himself. Such a stance demonstrates Joseph’s moral courage and his belief in poetry, as he beholds and bears his vision of our age. Joseph’s poems both confront the dark side of empire and see the world with tenderness, for its sensual, unbidden beauty.

This interview was begun by phone and continued over email in October and November of 2017.

Two geographies have haunted your poetry: Detroit and New York City (a third, Lebanon and Syria, also haunts them). Though you’ve lived for many years in New York, Detroit has figured powerfully in your work, and its meanings have continued to evolve in your poetry, now mostly interspersed as counterpoints to the imperial cosmopolitan landscape of New York. Could you talk about Detroit as part of your geographical imagination? How is Detroit a key to opening the door to your poetry?

I was born in Detroit in 1948. Until my wife Nancy Van Goethem and I moved to New York City in 1981, I lived in Detroit—or metropolitan Detroit, which includes Ann Arbor—all but the two years I spent in post-graduate studies at the University of Cambridge. The poems in Shouting at No One, my first book, are, other than a prologue poem and a poem partially set in Lebanon, entirely placed in Detroit, where I lived during most of the ’70s. Detroit’s meanings are, for me, first of all dictated by my family’s and my own histories in the city, as well as by the history of the Detroit that they and I inherited. My grandparents were Lebanese and Syrian Catholics who emigrated to the United States and, ultimately, to Detroit, shortly before World War I, where they ran grocery stores. They were among the first immigrants in Detroit from the Arab world.

My parents were both born in Detroit after the war. They were raised in Catholic grade and high schools, as I was. After World War II, my father and his brother inherited their father’s store, which, in the ’50s, became a grocery-liquor store. By 1960, the store could no longer support two families, so my father went to work at A & P as a meat-cutter, while also working at the store three nights a week. The store was badly damaged in the ’67 insurrection-riot-rebellion, and, in 1970, my father was shot and almost killed in a daytime robbery. I was born into a Detroit that was the fourth largest city in the United States, one of America’s greatest and most important cities. I’ve been aware of its significance since I was a child. Detroit is infused throughout my work, and I mean infused: its physical and metaphorical geographies, in a large and evolving sense, are an integral part of my imagination.

Your connection to Detroit and Michigan also includes, of course, the University of Michigan. How was your time at the U of M foundational to your growth as a poet? What role did it play in your poetic education?

I was at Michigan as an undergraduate from 1966 to 1970, and then again as a law student from the summer of 1973 to December 1975. I wrote my first poems in Ann Arbor—my freshman year, 1967. I was in Honors English, which at the time included, in my junior and senior years, a rigorous, superlative survey of English literature from Chaucer on. The first semester my junior year I took a seminar course, “Ezra Pound and the London Arts,” taught by Donald Hall, and during the second semester, I took Hall’s class on Yeats and Joyce. My first semester senior year I was in Hall’s advanced poetry creative writing course—Jane Kenyon was a classmate. Don was a wonderful teacher, imparting not only his skill as a poet, but also his critical skills. His love of poetry was unmatched. Galway Kinnell came to our writing class and read poems from Body Rags and, during the second semester of my senior year—winter, spring, 1970—Robert Bly was poet-in-residence.

Ann Arbor was then as politically charged as any place in the country. I remember Bly reading his work, and work by Vallejo and Neruda that he and James Wright translated, to a standing-room-only audience in one of the science building’s large auditoriums. That semester I received a fellowship, endowed by the Power Foundation, to study English Literature at Cambridge. It was an exchange fellowship between Michigan and Magdalene College, Cambridge—I was the third recipient. I was only able to do it because I received a high draft lottery number in December ’69—before then, deeply and morally influenced by the non-violence, anti-war Catholic Left, I had decided I was going to seek conscientious objector draft status. My last semester I also received a major Hopwood award for poetry—at that pre-MFA time, only seniors and graduate students could apply. Shortly after receiving the Hopwood Award, I met Robert Hayden, at a Phi Beta Kappa dinner for graduating seniors. Hayden, who received a post-graduate degree from Michigan and also a major Hopwood award, joined the Michigan faculty in the fall of ’69. His Phi Beta Kappa poem was “The Night-Blooming Cereus.”

So, after Cambridge, you returned to Ann Arbor to go law school.

Not immediately—I took exams at Cambridge in June of ’72, and returned to Detroit in late November that year. I then worked several months in Chrysler factories in Detroit—Lynch Road Assembly, where Plymouths were assembled, and a small plant on East Jefferson where prototypes for Chrysler’s next year’s model were made. I’d worked in factories before—I’ve worked in factories, in total, over a year or so. I began law school, a “summer starter,” in May ’73. I lived in a small basement apartment on Elm Street until January ’75, when I moved to Detroit to live with Nancy, who I’d met in Detroit, where she lived and worked as an artist for the Detroit Free Press. I commuted my last two semesters in law school from Detroit—we lived in an apartment on East Jefferson, on the river, near Indian Village.

After law school, I worked as a judicial law clerk for G. Mennen Williams, who was then an Associate Justice—later Chief Justice—of the Michigan Supreme Court. Williams was the Democratic Governor of Michigan from 1948 to 1960, a leading liberal, very much politically responsible for the ascendancy of Walter Reuter’s UAW. During the 1950s, he was the most progressive governor in the United States on issues of civil rights. In 1960, he became Kennedy’s Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs, and, shortly after Humphrey lost the election to Nixon in ’68, he became a justice on the Michigan Supreme Court. He had offices in downtown Detroit—my clerkship was from 1976 to 1978. After that, I joined the law faculty at the University of Detroit School of Law, where I taught until we moved to New York in ’81. During that time, I wrote the poems in Shouting at No One, except for “I was appointed the poet of heaven,” the prologue poem, which was a part of my Hopwood manuscript. I met Larry Goldstein during that time and, later, began publishing poems, essays, and reviews in the Michigan Quarterly Review.

In 1986, MQR had an entire issue on “The Image of Detroit in Twentieth Century Literature—for it, Larry published my poem “Sand Nigger,” and “‘Our Lives Our Here’: Notes from a Journal, Detroit, 1975.” The year before he’d published “In the Beginning was Lebanon,” which, with “Sand Nigger,” was in my second book, Curriculum Vitae. In 1988, I wrote an essay, “The Voices Behind the Law,” for MQR, on a groundbreaking book on legal language by Joseph Vining, who had been a professor of mine at the U of M Law School; in it, I mention others at the Law School—James Boyd White, Lee Bollinger—who were prominent in Michigan’s essential contribution to law and literature scholarship. Two poems of mine that appeared in MQR, “Sentimental Education” and “About This,” are in my third book, Before Our Eyes. In 2000, Larry published “Smokey Robinson’s High Tenor Voice,” a journal entry I wrote in 1975. Into It, my fourth book of poems, includes two poems, “I Note in a Notebook” and “News Back Even Further Than That,” originally published in MQR.

To continue reading, purchase MQR 57:1 for $7, or consider a one-year subscription for $25.

Image: Clark, Joe. Photograph of new cars being presented on the parking ramp of Cobo Hall in Detroit. From the November 17, 1960 issue of Life Magazine.