In my favorite story in Douglas Trevor’s most recent story collection, The Book of Wonders, a young novelist muses that “readers willing to take on fiction were looking for refuge from reality, and short stories didn’t provide much of a refuge.” Though meant to explain the lack of public appreciation for the short story, I cannot help but feel that this line also serves to explain the appeal of the stories in this collection. There is very little refuge in The Book of Wonders, particularly for its characters. With the figurative roof blown off their homes, we watch them in a struggle to cope that’s in turns futile and hilarious. There’s so much humanity in the collection, and perhaps this is what makes it feel so unsafe.

As much a sharp experiment in pathos as it is an ode to the bathetic almosts that comprise life as we know it, The Book of Wonders is a deft, clever rumination on the comedy and tragedy of reinventing oneself. Every story finds its characters gazing over a precipice. We watch them unravel, we watch them weave themselves back together again. His characters are divorcees and shut-ins, fanatics and flops. His characters, despite their alienation, are wholly accessible. Trevor’s prose is both warm and blunt, and the scope of these nine stories that comprise his second collection do not so much adhere to their theme as press against it. In the course of his collection, Trevor reworks Greek mythology, finds humor in the often bleak world of academia, and prophesizes a future form of personalized fiction that seems all too prescient.

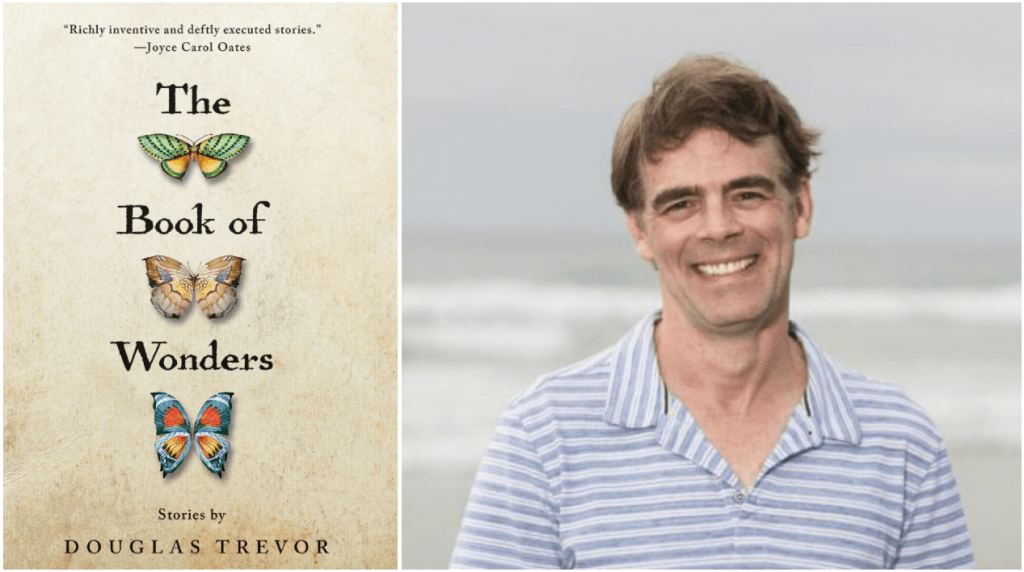

I recently had the opportunity to talk to Trevor about The Book of Wonders, the influence of academia on creative writing, and the transition between short fiction writing and novel writing (and back again.)

I noticed that a lot of this book centers around people trying to shake certain behaviors, to move out of a dark time in their lives, to break a certain pattern. Nearly every story in this collection starts on its protagonist’s first name, or otherwise a description of some ongoing behavior of theirs. Basically, these stories always start with a definitive understanding of character. There’s a lot of “always” and “never” in these first sentences to establish some fact about the characters that would then be deviated from.  Was this something you noticed as you were writing, or was it something you retroactively worked into the collection once you’d discovered its central thrust?

Was this something you noticed as you were writing, or was it something you retroactively worked into the collection once you’d discovered its central thrust?

I didn’t do much retroactive refiguring of the characters in these stories, or the ways we are introduced to them. But you’re right — a lot of the stories begin by establishing certain characterological habits and then testing these habits. So Theobald Kristeller spends his days looking at rare books at the British Library, and by the end of that story — “Sonnet 126” — he’s decided he’s finished with libraries. And Daniel in “The Librarian” — whose real name is withheld in the story until he introduces himself to Sasha, the young object of his affections — also leaves a library behind in his story. I was trying to pursue and experiment with the concept of wonder — first experiencing the wondrous in enclosed, mediated spaces, often represented by a character’s encounter with a book, and then next out in the physical world, where the wonderful is more threatening. Literally less bounded.

But not every character makes it outside, so to speak. In “Endymion,” Cynthia, an accountant, becomes enamored with a man named Damian Endymion who is very much associated with the outside world. He seems, although we don’t know for sure, to have been living outside before he begins to shack up with Cynthia. In this story, Cynthia cannot bring herself to trust Damian enough to leave her safe and enclosed world behind. This is a world in which literally all of her plants die, but still, she just can’t let it go. I think that’s true for so many people and that an inability to take risks is often what characterizes the most lonely among us. In “Faucets,” the mother — Liza Radrick — also ends up accepting the enclosed, claustrophobic nature of her community, too. So not everyone in the book makes it to another experiential plane. Sometimes people choose the safety of seclusion and loneliness over the dangers associated with new experiences. I was interested, in this collection, in examining this kind of choice.

These stories make a lot of hilarious and absurdist, albeit incredibly apt, observations about academia. I laughed my way through “The Program in Profound Thought,” in which a professor haplessly turns a university’s speaker series into an embezzlement scheme. You’re a writer and an academic, which is not an uncommon combination as of late. Besides inspiring some really clever stories, has being in academia had any other influence on your work?

Really, these stories offer a fairly somber depiction of the academy. Herbie in “The Program in Profound Thought” and Theo in “Sonnet 126” both have academic careers that fizzle, and both are looking for change as our time with them winds down. But, perhaps more pointedly, Charity Jackson, the central figure in “Easy Writer,” the last story in the collection, could not have a more illustrious academic career (she’s a world-renowned Latinist) and that’s still not enough for her. I think, to be honest, much of The Book of Wonders is processing what it feels like to be a mid-career academic. At a certain point in my own academic career, I began to feel that churning out articles on John Donne and William Shakespeare was something I could do, but that knowing how to do this maybe meant that I should try to do something else.

There are plenty of academics who reimagine their own approach to their fields in exciting ways, but scholarly discourse in my field — sixteenth- and seventeenth-century literature — is still incumbent very much upon being involved in the discourse that constitutes this field. And this is a very old discourse. Which is just to say that, for me, the footnote apparatus itself began to feel very onerous. One way to channel this restlessness was to let myself inhabit characters who have more or less thrown up their hands with regards to being “learned.” But all of these characters, from Herbie to Theo to Charity, still love the writers they went to graduate school to study: Milton, Shakespeare, and Ovid, respectively. Which is just to say that I’m fascinated by how books burden and enliven us at the same time — not just as academics but as fiction writers and poets, as well.

I love what you’ve said here, that “books burden and enliven us at the same time.” This isn’t your first collection of short stories — you’ve published a collection called A Thin Tear in the Fabric of Space that hovers around coping and grief. And your novel Girls I Know, which was adapted from a story in A Thin Tear in the Fabric of Space, does interesting work of exploring the notion of the simultaneous joy and frustration of writing and, to an extent, storytelling.

My reason for bringing up your other works of fiction is two-fold: First, your story “The Novelist and the Short Story Writer,” one of my favorites in the collection, makes a lot of hilarious observations about the two forms. Having written in both forms — and fascinatingly, about some of the same characters, such as Walt and Ginger in Girls I Know — is there a difference in your process? Was it difficult to transition back to writing short fiction after having written a novel?

To begin at the end, it was difficult to transition back into short fiction, and I never really made it all the way back. That is, with the exception of two or three stories in The Book of Wonders, all the rest are longer than those in my first collection. The narrative clock to which I kept time in Girls I Know is more leisurely than that of Thin Tear, and it shapes, to a degree, some of the stories in The Book of Wonders. I can imagine a novel shaped by short scenes, in which the tempo of short fiction is maintained, but that wasn’t the case for me in Girls. Partly this was due to my interest in the passing of time and my desire to have this passage leach into the story. While there is backstory in many of the stories in Thin Tear, the action of these stories is usually restricted to a few days/weeks.

In Wonders, I wanted time to unspool a little more. The last story, for example, “Easy Writer,” begins in scene, then has an expository section that covers about thirty years of the central character’s life, then goes back into scene, then into two short-short stories, each “told” in the brain of a different character, before returning to a final scene. In terms of experimenting with pacing and forms of storytelling, this story just feels more novelistic to me, in part because it requires more pages to stage these different narratives than would a story tightly restricted to scenes that covers a shorter period of time. At the end of the day, though, what I really wanted was for the experience of readings Wonders to feel fundamentally different from reading Thin Tear, even though — as you rightly observe — both books are constituted by thematically linked stories.

Do you see yourself returning to any of the characters in The Book of Wonders? Or do you feel that these stories have more or less expressed what you needed to about these people?

I feel like I could say more about every character in every story. If a short story I wrote exhausted what I found interesting about its central character, that would rankle me. It would make me think that the character wasn’t supple enough to deserve attention in the first place. That said, I don’t have any plans to return to these characters, but I think about what they might be up to, as I did when I was writing about them. They’re still active in my brain.

Find out more about Trevor’s work at douglastrevor.com.