Transcript of the Hopwood lecture delivered by Andrea Barrett at the University of Michigan, April 17, 2001. Reprinted in MQR’s Summer 2001 issue.

I’m delighted to join you today. In the last few years I’ve had the pleasure of supervising some graduating MFA students, participating in several classes and workshops, and judging the Hopwood prizes in short fiction—so I know what a talented group of writers you are, and I have some sense of what an important role these prizes play. Still, it’s worth remembering that prizes are gravy. Although at their best they represent welcome affirmation from the outside world, they serve largely to celebrate work that’s already done and a path that’s already been explored. Prizes don’t acknowledge the failures along the way, the false steps, the discarded stories or novels: the essential mistakes and fumblings that often represent our truest experiences as writers, and that signal our growth. They don’t acknowledge the fact that, for almost all of us, writing is a process of finding our way through unknown territory.

When I’m in danger of forgetting this fact, Nabokov’s tart comment, in his essay on “Good Readers and Good Writers,” serves to remind me. He writes:

To minor authors is left the ornamentation of the commonplace: these do not bother about any reinventing of the world; they merely try to squeeze the best they can out of a given order of things, out of traditional patterns of fiction. The various combinations these minor authors are able to produce within these set limits may be quite amusing in a mild ephemeral way because minor readers like to recognize their own ideas in a pleasing disguise. But the real writer, the fellow who sends planets spinning and models a man asleep and eagerly tampers with the sleeper’s rib, that kind of author has no given values at his disposal: he must create them himself.

After describing the fruitful chaos of this newly created world, Nabokov continues,

The writer is the first man to map it and to name the natural objects it contains. Those berries there are edible. That speckled creature that bolted across my path might be tamed. That lake between those trees will be called Lake Opal or, more artistically, Dishwater Lake. That mist is a mountain—and that mountain must be conquered. [1]

Implicit in Nabokov’s comment is the idea that in the course of trying to climb that mountain, and while searching for that speckled creature, we may find ourselves considerably lost.

When I was writing my last novel, The Voyage of the Narwhal, I immersed myself in the journals and letters of nineteenth-century Arctic explorers. Some of these fed the novel directly, but others I read for the sheer delight of their language and vision, even though they were about expeditions from the wrong countries, at the wrong time, headed for the wrong place. When I felt guilty about doing something so easy to construe as a waste of time, I consoled myself with the idea that I could never know beforehand what might be useful, or where the things I found might lead me. I couldn’t have expected, for instance, the way these stories made me think about the nature of exploration in general; or about how that relates to writing.

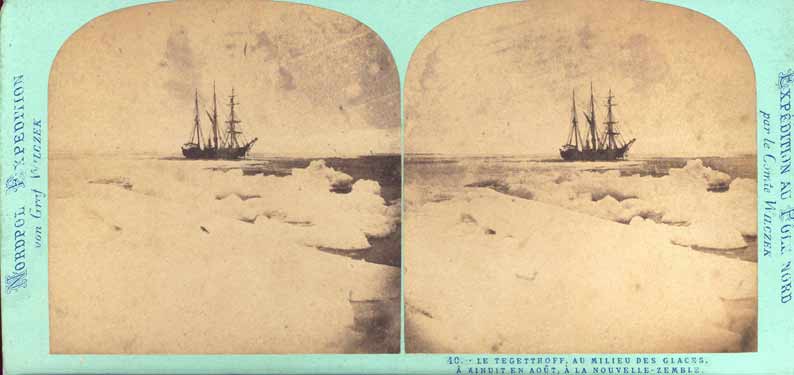

One story I bumped into, and couldn’t use at the time, was about the Imperial Austro-Hungarian North Pole Expedition. In July of 1872, Karl Weyprecht of the Austrian Navy, Julius Payer of the Austrian Army, and a crew of twenty-two men set off to test a theory proposed by the German geographer Petermann: that by following a branch of the Gulf Stream, an ice-free passage might be found to the north of the island of Novaya Zemlya, which arcs north and east of Norway and above Russia’s northern coast. Through this passage, Weyprecht and Payer thought, a ship might reach the North Pole. They expected open water; they expected to sail to the Pole. Failing that, or in addition to that, they hoped to find between ice and land a Northeast Passage leading to Siberia and China. Failing that, or in addition to that, they hoped to explore unknown territory.

The Tegetthoff, a three-masted, 220-ton bark, left the tip of Norway in July, equipped and provisioned for two and a half years; by August it reached the west coast of Novaya Zemlya. Shortly afterward, still in sight of that sickle-shaped island, the ship was seized by the ice and swept northward. “We were, in fact, no longer discoverers, but passengers against our will on the ice,” Payer wrote.

As we sat at our breakfast, our floe burst across immediately under our ship. Rushing on deck we discovered that we were surrounded and squeezed by the ice; the after part of the ship was already nipped and pressed, and the rudder, which was the first to encounter its assault, shook and groaned. . . . Noise and destruction reigned supreme, and step by step destruction drew nigh in the crashing together of the fields of ice. [2]

All that fall and winter the frozen ship drifted north. It was dark for two months; the temperature hovered near fifty below. The men shouldn’t worry, their commanders said; when spring came the ice would open and the Tegetthoff would sail away. Meanwhile the men, who saw no one but each other, waited for their home to burst into pieces.

When spring came, they found that the ice, and their ship along with it, was now drifting steadily northwest. Northwest, not northeast—why were they moving in that direction? The crew of the Tegetthoff dug and sawed and chipped at the ice, trying to free themselves as they continued drifting. Tired and hungry and in despair, they realized, as the end of the summer of 1873 approached, that they might be imprisoned for a second winter. By then, “Not a man among us believed in the possibility of discoveries,” Payer wrote. “Though discoveries beyond our utmost hopes lay immediately before us.” [3]

Land appeared through the mist on August 30th—not the North Pole, but land no one had expected. The Tegetthoff, still caught in the ice, drifted away from it and then back toward it. When the crew finally set foot on that desolate place, they found snow and rock and broken ice, along with a few meager lichens. Payer and Weyprecht, in honor of their Emperor, named this uncharted place Franz Josef Land.

With sledges and dogs they explored their discovery throughout their second winter; Payer and a small party marched 180 miles north in temperatures that dropped to fifty degrees below zero. From a high point, Payer believed he saw further lands lying north across ice and open water. Before he and his men struggled back to the ship, he named his vision Petermann Land.

In May the crew abandoned the Tegetthoff and began a journey south, by sledge and small boat. Snow, ice, pulling, sailing, freezing, digging, hunting—the journey seemed hopeless at first; they made no progress. But in August they were blessed with a peculiarly warm spell; the ice opened, water appeared; there was drift ice and then the open sea. They rowed and sailed, as they’d always expected to do, and on August 24, 1874, they encountered a Russian fishing ship. Franz Josef Land, Payer would announce, is made up of two great islands and is the size of a continent. Later explorers would find it to be a small cluster of tiny islands.

In contrast to the voyage of the Tegetthoff is the expedition led by the Norwegian explorer Nansen. From the experiences of the Tegetthoff, and the relics of a subsequent expedition, Nansen deduced that ice must drift northwest across the Polar Sea, perhaps across the Pole itself. Rather than trying to sail around the ice—rather than trying to fight it—he determined to drift with it, purposefully seeking the fate of the Tegetthoff by freezing his ship into the great clockwise current. The ship he designed, called the Fram, was meant to ride above the ice when the floes squeezed in, rather than being caught and crushed.

The Fram steamed away from Christiania harbor in June of 1893, making her way east to the New Siberian Islands before heading north with her crew of twelve Norwegians. By September the Fram was frozen—purposefully, with full intention—into the ice-pack north of Bennett Island. Drifting slowly, but always to the northwest, the Fram moved through a winter, a summer, a second winter. The ship was comfortable, warm and safe; the journey was going as Nansen had wished and his theories were being proved. Despite this he felt restless. Cut off from everyone but his shipmates, he described the voyage in his diary as “really neither life nor death, but a state between the two.”[4] As the confinement wore on him, he wrote:

. . . at times this inactivity crushes one’s very soul; one’s life seems as dark as the winter night outside; there is sunlight upon no part of it except the past and the far, far distant future. I feel as if I must break through this deadness, this inertia, and find some outlet for my energies. Can’t something happen? Could not a hurricane come and tear up this ice, and set it rolling in high waves like the open sea? [5]

The Fram was drifting, as he’d wanted; west, but further south than he’d hoped. At about eighty-four degrees north latitude—350 miles from the Pole—he determined to leave the ship and try to reach the Pole on foot, while the Fram continued on her journey. He and a companion left the ship on May 14, 1895, when they were roughly in line with Franz Josef Land; they’d reach the Pole, they thought, in fifty days, and then march back. After twenty-four days of fighting hummocks and pressure-ridges, wrestling with capsized sledges and torn kayaks, Nansen realized the ice was moving south, driving them backward as fast as they walked forward. A little above eighty-six degrees north latitude, he turned back.

It wouldn’t be such a bad trip, he thought; Petermann Land, which Payer of the Tegetthoff had once described seeing, should lie between him and Franz Josef Land, easy enough to reach. But Petermann Land turned out to be a mirage. Nansen and his companion reached Franz Josef Land only after a long struggle, so late in the season they had to winter there. With a shovel made from a walrus’s shoulder-blade they dug a hole and draped it with hides, making a home for the long Arctic night. In May of 1896, after almost nine months in that hut, they moved on again; in June, in the southern part of Franz Josef Land, by remarkable coincidence they met a member of an English expedition; by August they were home. They hadn’t reached the Pole, but they’d survived. A few weeks later they were reunited with the Fram, which had drifted west with the ice until she was north of Spitzbergen and then had steamed home.Two voyages, then; both successful in their own ways. Both the result of long preparation, careful planning, full knowledge of all the prior explorations. During the voyage of the Tegetthoff, something was found by searching assiduously for something else. During the voyage of the Fram, the clockwise current that had existed only as a theory was found to be true in fact.

Similar plans and preparations, similar outcomes—but different experiences and states of mind during the journey itself. I try to imagine how these might have felt to the crews as they were experiencing them. Not how they felt after they’d returned successfully—but how they felt in the long dark middle. We might guess, for instance, that the crew of the Tegetthoff felt panic and terror before they stumbled on Franz Josef Land; their journey was made meaningful only by a discovery they couldn’t have predicted. We might guess, similarly, that the crew of the Fram were in a much calmer state of mind. One journey was full of anxiety, the other more serene and hopeful. Yet both yielded something useful.

You will have guessed, by now, where I’m going with this; at least in my mind there are parallels between these two expeditions and the explorations we make as writers. Not, of course, that we face such hazards or endure such fearsome hardships, nor that we make discoveries that alter all the maps. The parallels are more modest, and have to do with the way we plan and carry out our imaginative journeys.

Sometimes, not often, I’ve found the writing of a story or a novel to resemble Nansen’s smooth and well-planned voyage. Sometimes I know, roughly, where I’m going; sometimes I can also guess the routes by which I might reach that destination. Usually, though, my experience has more closely resembled that of the hapless souls aboard the Tegetthoff.

In 1997, I finished working on the novel that had first led me to reading about the Tegethoff and the Fram. The Voyage of the Narwhal is concerned, among other things, with American naturalists exploring in the Arctic during the 1850s. If you looked at it now, it might appear to have been built on a rational plan, by a person who knew where she wanted to head and how she wanted to get there. In its published form, it begins in May of 1855, as the main characters prepare to head for the Arctic, and it’s told in a third-person omniscient voice that incorporates the points of view of many characters. Yet this was how the novel opened during most of 1994:

This is how I began my sporadic career as a polar wanderer. At the age of twenty-three, by a combination of bad luck, good connections, and sheer serendipity, I left my home in Philadelphia and found my way onto the sloop of war Peacock of the United States Exploring Expedition, commanded by Lieutenant Charles Wilkes. Among the naval personnel that crowded our squadron of six ships, I was one of that group of ten civilians referred to, somewhat disparagingly, as “the Scientifics.”

I’ve been telling this story for years. But in brief: From 1838 through 1842 we cruised through the Pacific, from the coasts of South America to the Feejee Islands, New Zealand and New Holland, the Sandwich Islands, the Oregon Territory and more. Along the way we charted some fifteen hundred miles of the AntArctic coast and proved the existence of that seventh continent. . . .

In the various Expedition publications—oh, some have been published, I grant you, incomplete and tardy but at least they have seen the light, not like those that have been dismissed outright or so long delayed that now they will never appear, now that this terrible war is upon us—in those you will find listed the other nine Scientifics, but never the tenth, which was me: Erasmus Darwin Wells. There is some justice in this. I was present only as Titian Peale’s assistant, allowed to join at the very last minute, never paid and never formally part of the Expedition.

It’s excruciating for me to revisit this draft, which is almost perpendicular in its style and approach to the final result. Time, place, person, tone—everything about it is wrong, most crucially the voice. During the year I worked on this version, I wrote 135 pages, none any better than what I just read. Working on them was like trudging through waist-high snow on a moonless night. Almost all the time, I understood that I was lost.

Yet from that beginning I did eventually discover who Erasmus was, and who his companions were, and something of the book I actually wanted to write. How did I get from the one to the other? That’s a reasonable question, to which you might like an answer. But I can’t give you one, or not an honest one; even to me, this process remains a mystery.

When I was a beginning writer, I’d go to classes and lectures hoping for advice, and what I always seemed to hear was that there was one real way to write. Each of the people I listened to would then profess a way that contradicted the other ways I’d heard professed; and all those ways would contradict my own experience. I’d leave those lectures in despair, thinking I’d never be a real writer.

Later, slowly, I began to see that there was no singular way. The secret of writing, I came to think, was that there was no secret; only a life’s long, patient process of exploration. The historian William H. Goetzmann has written that exploration

. . . has rarely if ever been viewed as a continuous form of activity or mode of behavior. The words “exploration” and “discovery” are most often and most casually linked in the popular imagination simply as interchangeable synonyms for “adventure.” But exploration is something more than adventure, and something more than discovery. . . . The accent is upon process and activity, with advances in knowledge simply fortunate through expected incidents along the way. It is likewise not casual. It is purposeful. It is the seeking. It is one form of the learning process itself. . . . Discoveries can be produced by accident. . . . Exploration, by contrast, is the result of purpose or mission. [6]

Training oneself to explore—as opposed to simply making occasional, random discoveries—always requires prior knowledge of the known. Once we’ve learned as much as we can about our craft, we may then find it useful to leave that knowledge behind temporarily and put ourselves in a position to be lost. But we can’t shed that knowledge until we’ve acquired it; we can’t unlearn before we’ve learned. As beginners in a new field, we may have a sense of not wanting our own unique vision to be drowned by all that’s preceded us; of not wanting to be hemmed in by tradition. Yet it always turns out that there’s no point in driving blindly into the ice without understanding who’s been there before, and who’s found what. How can we know we’ve found new land if we can’t recognize the old? Without some knowledge of nineteenth-century journals of Arctic exploration, as well as some understanding of how other writers have approached the problems of using historical fact in fiction, I doubt I would have realized how far I’d gone astray in my own initial explorations.

What I’m trying to say is nothing more complicated than this: that writing—like drifting through the ice in search of new lands, like science, like life—is a constant process of exploration. That discoveries are not random; that chance, as we’ve always heard, favors the prepared mind. We may think we know where we’re going; we may be wrong about this, or right; we may have our brilliant theories confirmed, or have them shattered. Yet the journey may yield something either way. And even if it fails—as it will sometimes fail—those failures may yield unexpected things. One more story, this time a brief one.

When Nansen set out on the Fram, he was guided not only by the voyage of the Tegetthoff, but also by the failure of another expedition. In 1879, the American explorer George De Long set off on the ship Jeannette. From San Francisco the Jeannette went northward through the Bering Strait, headed for Wrangel Island and then the North Pole. Unintentionally, unexpectedly, it was caught and frozen into the ice. For two winters the men drifted in the clockwise current without seeing any land at all; as De Long noted, “this is a glorious country to learn patience in.” [7] Perhaps, he thought, they might drift to Franz Josef Land. Instead, the Jeannette was crushed by the shifting floes.

In three small boats, De Long and his men fought their way to the nearest land, the New Siberian Islands; the northernmost one, which they named Bennett Island, became the place from which Nansen would later depart. As they struggled on toward the Siberian coast, one of the boats was lost entirely, its crew never seen again. The second made its way to safety. De Long and the men in the third boat landed at the far edge of a swampy river delta. Trapped there for the winter, they all died. When their bodies were found the next summer, De Long lay on his back, reportedly with his left arm raised. A few feet behind him lay his journal, as if his last act might have been to toss that written record, his legacy, to the safety of higher ground.

While the snow was drifting over the bodies, fragments of the Jeannette kept moving on their secret, clockwise journey. A few years later some relics from her—most notably a pair of oilskin trousers—were discovered half a world away, on the coast of Greenland. It was news of these that inspired Nansen’s voyage on the Fram: from their long, silent journey, he deduced that the ice must indeed drift implacably northwest across the polar sea.

What did Nansen need to make that leap of understanding? He needed evidence—the floating pants. He needed enormous knowledge about his field—famously curious and persistent, he studied the records of every previous expedition north. He needed the kindness of strangers—his work depended largely on the successes, and failures, of those who’d gone before him. After that all he needed, but for time and funding and an eager crew, was a willingness to get lost while he searched for confirmation of his theory.

I got lost writing this lecture; parts of it have existed in different versions, combined in different ways, for some time. At one point I thought it might be about the connections between art and science; my notes initially included a lot of material about Darwin and Faraday and the nature of scientific discovery. Mary Shelley’s romantic vision of the Arctic, with her Frankenstein’s monster bolting across the ice-pack in a dog-drawn sled, also seemed useful for a while. Later Virginia Woolf lent me some words and then took them back. As I fumbled toward a final shape, I realized that almost anything could claim a temporary berth. If you could see the tracks I left on my way here, you’d also see how much has had to go over the side.

In the end, while the central stories—the voyages of the Tegetthoff, the Fram, and the Jeannette—have stayed the same, their meaning has shifted. You would have to contact Dr. Freud to understand why only during the last month did I make the connection between those stories and the troubled, wandering voyage of my own novel, which I had never intended to mention here.

Writing this lecture has been a process of reapproaching the central stories from different angles, trying again to understand what they mean to tell me. This week, standing here before you, they seem to be sending the simplest message of all: that it’s time for each of us to go exploring again. I thank you for reminding me of that, and I wish you all the best of luck on your own journeys.

NOTES

1. Vladimir Nabokov, Lectures on Literature (New York: Harcourt Brace & Co., 1980), 2.

2. Jeannette Mirsky, To the Arctic!: The Story of Northern Exploration from Earliest Times to the Present (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1948), 175. For a fictionalized account of this voyage, see Christoph Ransmayr’s excellent novel, The Terrors of Ice and Darkness, translated by John E. Wood (New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1991).

4. Eric Leed, Shores of Discovery: How Expeditionaries Have Constructed the World (New York: Basic Books, 1995), 12.

5. Fridtjof Nansen, Farthest North (first published in 1897, Modern Library Exploration reprint, 2001, 16l).

6. William H. Goetzmann, Exploration and Empire: The Explorer and the Scientist in the Winning of the American West (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1966), xi.

Image: Photo of The Tegetthoff encountering ice on an expedition to the North Pole. 1872.