Nonfiction by Molly McQuade from our Winter 2017 issue.

Blitzen!

Brooklyn produces unexpected sounds from a tremulous larynx.

Waiting for the F train at the Jay Street stop, I’m summoned from my stupor by “Jingle Bells.” It is late September and eighty-eight degrees.

Since when did Santa begin taking the subway? The humid shawl of sinkhole fumes parts for me.

Instead of finding a sweaty, humming Christian clasping a hymnal, I face a slender Japanese fluttering a bow at the base of a tilted, gracefully scrawny three-stringed instrument that culminates in a couple of tuning pegs. Yuletide!

Because he’s ungrudgingly gung-ho, or maybe because Christmas is coming from him in this tune on a sultry Friday afternoon in the city that is too hot to live in, people are hurling damp coins every which way at him. They want their snow.

He never counts the money. He never smiles. Our sleigh is coming.

To me this sums up the music in Brooklyn. You don’t need to do it “right.” You’ll never do it “right.” You’ll never do it right at all. But there’s another way.

In pursuit of that rough and ready insight, I’ve been listening to the right of wrong and to the wrong of right in Brooklyn music for a couple of years. Here follows a smidgeon of the music in Brooklyn and a little of the Brooklyn in music, overheard.

Harmonica and the mensch

The swerving howl of a harmonica when blown will sound plural and singular, as though it were more than one instrument, crowing over that fact. The song of a harmonica speaks first for the musician, of course. But it can also speak, by its nature, in many tongues and tones at once, and for everyone—or against us, or even both at the same time. And with fury.

Or, with forlorn repudiation. Or, with listless regret. With juiced effrontery. Sardonic contempt. And with fury, redux.

All of these emotions, and more, tangle everything up. They belong boisterously to the harmonica and its menschy, bleating discontents.

During the Brooklyn Folk Festival of 2016, I made a beeline for the harmonicas, all set to compete for some trophy or other. I can’t recall who won the contest. But I learned this much: certain harmonica musicians try to make the harmonica sound even more like itself, while others—the virtuoso tricksters—aim to make it sound as little like itself as possible. I don’t take sides in these bristling campaigns.

The Folk Festival is an enterprise of the Jalopy Theatre and School of Music in Red Hook, where I first heard the wistfully ferocious klezmer ensemble Litvakus, led by Dmitri Zisl Slepovitch, whose music (Belarussian “raysn”) sounds an emergency alarm for a culture while also conducting what he terms a “mitzvah.” On call as well at the festival were the Hickhoppers, the Pearly Snaps, the Old Scratch Sallies, the Down Hill Strugglers, and the Whiskey Spitters, to name only a few.

In south Brooklyn, Jalopy perseveres without a subway stop to call its own. You’ll walk from Smith Street across the Brooklyn Queens Expressway from high above to reach it. Here the pressed-tin ceiling is painted an indescribable hue of archaic glow. An unshuttered skylight pours wanton clarity on battered pew seating. Good thing those pews aren’t bolted to the floor. Co-owners Geoff and Lynette Wiley bought the three-story brick rowhouse at 315 Columbia Street in 2005 on their very first day in Brooklyn. As Chicagoans, they’d long doted on that city’s beloved Old Town School of Folk Music, then decided to grow their own with funds earned from a savvy real estate investment. Besides hosting countless performances, Jalopy issues recordings on its own label. Geoff Wiley runs a musical repair business. Music lessons are given six days a week.

Professional musicians head here in droves. So do the others, young or not, toting music cases of all shapes and sizes. Jalopy’s weekly open mike night is held in high esteem. Each Tuesday at 9 pm, Ernie Vega hosts, with these rules cheerfully enforced: “Two songs each, or eight minutes—whichever happens first.”

You might hear a song like “Nun on the Run,” as played by somebody called Alistair. Or you might find a measure of musical guidance from the husky-voiced regular known as Pete. (Pete plays Elvis with assorted scruples.) Or you might close out a Tuesday evening at Jalopy by listening to a stripped-down version of “The Sound of Silence” as played on solo sax by Ricky from Staten Island, his graying Robin Hood locks swaying just slightly, like a librarian getting ready to liberate his own cardigan from its buttons.

“Jalopy was made by hand,” notes singer-songwriter Feral Foster, who teaches music there and curates the weekly Roots ‘n’ Ruckus series. His raucous fusion of blues, gospel, rock, a touch of Patsy Cline, and maybe just a nod or two to the French troubadours takes its cue from his adopted name—and from the scarlet sequins of some favored Feral outfits.

Newness

When I hear ‘“Oblique Music for 4 plus (blank)” by Jason Treuting performed for the second time in only a few weeks, I try to envision what the music might be describing. I do not envision Brooklyn. But maybe I should. For that is where the music comes from. This music is Brooklyn, regardless of opinion. To know what Brooklyn is now, you’d have to hear it.

Brooklyn is, among other things, the base for So Percussion and for Treuting, at 20 Grand Avenue in Williamsburg, where tall rabbinical men patrol the boulevards. When I show up at the So studio for periodic Brooklyn Bound concerts, often featuring the So musicians as well as their various invited guests, the place tends to be packed and ecstatic, teetery with musicians who’ve trudged in from all over.

Treuting serves as a founding member of the quartet. When I hear “Oblique,” it is played both times by So with another quartet, Jack. Expressing a warmly grave clarity of symmetry that’s hard to miss, “Oblique” is about music singing to itself. It inquires, and then it answers, again and again.

The symmetry emanates from a two-note stroke that provides the music with its evocatively minimalist basic structure. Minimalism’s power to evoke is often underrated. What does the reiterative plangent stroking of “Oblique” suggest, at least to me? The voice of a sorrow, saving itself by saying itself. The players bow, either vertically (the four percussionists) or horizontally (the string quartet). As the strokes accrete with a gratefully severe abundance, so does the slow, somber visual impact extend itself, almost prayerfully. This is about the unity of unison. It is about an agnostic fidelity. The musicians in Treuting’s sonorous writing are touching something, in order to touch something.

“Oblique” is about more than that. It’s about continuing and continuity. It is about building something to last without neglecting its mercurial core fragility. In it I overhear Treuting saluting Steve Reich. Still, the greeting to Reich asks Reich to yield with tact to Latin rhythms, rhythms which may come to us courtesy of Copeland. And it asks Reich to yield as well to a contrarian crescendo, as if So were informing him, with a spry, exclamatory thank you: Yes, we have found our freedom—our freedom even from minimalism. We are.

___

Whenever I end up liking what is called, optimistically, “new music,” meaning music like So’s that is ahead of its time, presumably, this is partly because, if left to my own devices, I probably could never have imagined that music. All I can do is listen.

Left to myself, I most likely couldn’t imagine a Bach partita, either. Yet the conventions of Baroque music have themselves become familiar. Even when eavesdropping on a partita I’ve never heard before, I can predict it. I can hum along.

By contrast, what is called, with gumption, “new music,” remains very much a work in progress. I can’t build it, but perhaps I should. I can’t build it, but if only I could! Therefore, I hear it with a certain tingly suspense. Innocent as corn, I tend to my ear alone.

When I hear new music and like it, I can almost never describe it, which I like as much as I like the music. When I hear new music and like it, the music doesn’t seem to be describing anything, either. Yet it may not be irrevocably abstract in its impact or aplomb. At its best, the music seems to be both unbeholden and unlimited. It creates, or can create, its own style and meaning. I can’t find the source. I can’t find the referent. I can’t anticipate what comes next. Usually, too, I can’t remember it.

To seek new music in Brooklyn, look no further than National Sawdust. Williamsburg is filled to the brim with all kinds of music, so it makes perfect sense that Sawdust, a venue devoted to conspicuously inventive or vanguard music, came to roost there more than a year ago. Housed in a renovated sawdust factory, and orchestrated by a complex array of curatorial objectives, administrative officers, and assigned liberties, Sawdust offers a space that feels intimate yet seemingly widens to fit a curious range of artistic occasions.

All of those owe something to the setting. Sawdust’s mosque-like paneled ceiling and surrounding walls present the eye with a seductive opportunity for tested repose. While listening, or before, you can explore visually the intricately abstract enclosure without ever feeling obdurately enclosed. The patterns never pall, perhaps since they never end, thanks to the way they swivel somewhere between the symmetric and the not so. These are lines to follow and to veer from, with enough diagonals for freedom. The shadows matter, altering apparent details of scale and adjusting one’s assumptions about what it means to be large or small. The state of mind inspired by the physical place is induced by a fresh set of unlimiting limits, like a new sky.

When in December 2016 I heard the Ghanaian drummer Gideon Alorwoyie and the Mantra Percussion Ensemble revisit at Sawdust the origins of Steve Reich’s “Drumming,” which was written after Reich’s sojourn in Africa with Alorwoyie, I was able to confirm a previous hunch of mine about that music. Alorwoyie played his own music, followed by a portion of “Drumming,” so we could compare them. The composition for nine percussionists, voice, and piccolo has always reached my ear with the elegant importunity of a subtle yet insistent invitation. What do Reich’s drumbeats, falling like ordained raindrops, invite me to do? They urge me, but politely, to stop doing anything, to depart from myself, even from my own hearing. “Drumming” asks me to tread near to trance.

As Alorwoyie made his own music with several other drummers and a dancer, they exemplified the trance. My only remaining question, whether critical or silly, is this one: does a trance mainly embody, or does it disembody, and what is the difference?

I was fortunate to hear So Percussion’s performance of “Drumming” during the summer of 2016. With Reich watching from the wings, its crisp version enunciated resolutely the music’s mesmeric rhythmic voices. Josh Quillen of So took charge of these, with help from his friends. In these hands “Drumming” was less about hovering than when Reich’s own ensemble plays it—less about a mystical merging of sounds and more about articulating each and every stroke. The So version was more finite, more physical, and thrillingly matter-of-fact.

Reich’s recording of “Drumming” maintains an interest in the continuous present, but only in the edge of the present as it promises to vanish. By contrast, So’s approach moves affirmatively forward with meticulous, adamant clarity. The present can be known so well and so clearly, there’s no room for doubt.

___

What do percussionists have that other people don’t?

They have unison. They have unison as an assumption, available to them anytime they want.

I don’t. I can’t. I’m just another pulseless one, that damned soloist. Yet while I can’t summon any unison alone, I can infer it or appreciate it while listening to percussion. That’s because, although I beat no drum, I am beaten by each one.

Adam Silwinski of So mentioned in his program notes on “Drumming” in Playbill last July that “the percussion orchestra in Western classical music [can] become . . . an appropriate vessel for sweeping visions of musical unity.”

When I ran into one of his So teammates by chance at the new Met Breuer Museum one sweltering Sunday afternoon, I hastened to ask Eric Cha-Beach if unison means something in particular to percussionists like him.

He said yes, it does, because percussionists depend on rhythm as their mainstay, not on pitch, and unison is an unusually unequivocal form for rhythm to take.

I felt that myself, one night at BAM. In September of 2014 at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in Fort Greene, I waited in line for three hours in hopes of cadging a returned ticket to the sold-out performance of “Drumming,” to be performed by Reich’s own ensemble, on the bill that evening with work by Philip Glass. Our long line of hopefuls sought its own tacit unison. Only one ticket was returned, and it went for a steep price to the man in front of me; I was second in the line. When, to my astonishment, the box office released five free tickets at the very last minute, I found myself perched in a lower-tier front box, closest to the stage, with an ideal view of the utterly entrancing dance-like proceedings.

Just before “Drumming” commenced, Philip Glass stole into our box by himself and discreetly took a seat. Although a Manhattanite might cynically hope he’d start texting, this once-and-future Brooklyner observed with interest as Glass sat in stark, silent immersion for the complete duration of “Drumming,” exactly like an acolyte.

Radio days (and nights)

Waking up is less difficult and more pleasant on this Monday of all Mondays in Brooklyn after forty-eight hours of insistent cloudbursts. Yes, it is easier—if and only if I wake up, slowly, to Thelonius Monk, circa 1967, Paris.

Who’s doing this for me? WKCR, the student-run Columbia University radio station.

Groggy at first, I gradually realize it’s WKCR’s incarnation of Monk, because not only do I overhear that beautifully disjunctive, thrifty singing tone of his piano, but also, every now and then, a human undertone speaks to me as well. The undertone, that of a mild-mannered announcer, who rarely stoops to announce much of anything, whispers ever so modestly the name of what was just played and of what else will soon follow. The undertone does not tell me what to eat for breakfast, which toaster I should hurry up and purchase, or even what the weather is.

No palaver. None. Not ever.

Monk plays those downward-moseying, stark running notes. And then he plays thin, chiming chords. To be honest, I cannot describe what he really does when he plays.

In due course, with my mind rearranged by Monk, I’m able to head out the door.

Thank you, WKCR.

___

A few hours later, Phil Schaap pipes up on the air to proclaim, with good cheer, that this very day, October 10, marks the ninety-ninth anniversary of Monk’s birth and the seventy-fifth anniversary of WKCR’s.

On October 10, 1941, as Schaap remarks, a fledgling WKCR crew journeyed to Minton’s at the Hotel Cecil, in order to record a house jam session including the young Monk. It is a tradition to celebrate his birthday at WKCR by playing all Monk for twenty-four hours straight. Schaap unearths and plays that 1941 recording.

“I’m not that old,” Schaap assures whoever’s listening.

“I’ve been here for forty-seven of those seventy-five years,” he enumerates carefully. “I hope we have a future. This is our past.”

To bend the ear that far back will loosen a quorum of emotions, perhaps. About that Minton’s jam Schaap comments, “They are at the dawn of [Monk’s] discography and the beginning of our station.” He confides, “Today is a momentous day. We’re playing the same guys we were playing then.” Few would disagree when he declares, “It’s present-tense music forever.”

But let me make a confession: I’ll probably always be a foreigner in the land of jazz, which confers on me peculiar privileges and punishments. Always WKCR helps me with this. For I come to jazz, after all, with a weird dual citizenship in classical music and blues. We were forbidden as children to play any music except Mozart’s, et cetera. During a longish adult apprenticeship in Chicago, I found a home in blues, also. Of that New York seems to have very little.

Still, when I come home late, very late, last night, after staring down dark streets deserted by all but a grunting goose, I turn the key and switch on WKCR. Soon, to my shock, I’m swallowed up by joy to hear the rattly shrieks of Little Walter at his harmonica again. So Chicago blues, too, is welcome on upper Broadway, then? The Columbia student named Elizabeth, who says no more than to identify herself, pilots Little Walter smoothly into the wee hours.

Singing screaming

What is the difference between a song, a scream, and a weeping caterwaul?

Lately I’ve been wondering, since beginning to explore the craft of the scream and the caterwaul myself. I’m an amateur at this. I do not sing. I never sang. Of course, I could. (I can.) But I never sang meaning it.

Regardless, recently I’ve begun to open up a portion of unoccupied space in my imagination to the singer.

Several people are responsible for my change of mind. Two are Jeffrey Gavett and Hilary Gardner. Another is Tamar Korn, who sings most Mondays in Brooklyn with Brain Cloud.

I don’t know how Jeff Gavett would answer my question about how song, scream, and caterwaul differ. Yet I’m inclined to believe that he could phrase any sound, or any sequence of sounds, imaginable or unimaginable, and make singing into something it wasn’t before he opened his mouth. Gavett is strongly wooed by untamed musical extremes. I first heard him at Roulette in Boerum Hill during an installment of the annual Resonant Bodies festival on September 11, 2015. That feels like last Friday. It keeps feeling, in fact, more and more like last Friday. I doubt I’ll lose the feeling anytime soon.

What Gavett did with unblushing faith was to fill his forty-five-minute program entirely with newly commissioned a cappella songs, none of them performed before in public. At Roulette, a big, dark space which had also played host weeks before to the startling, landmark Lukas Ligeti birthday concert, and this November to the five-hour-long, astonishingly saturating Connie Crothers memorial concert, Gavett stood up all alone and enflamed any waiting ear with a giddily inventive Joycean tumult of hyper-articulated sound.

I believe it may have meant nothing. It meant nothing I could translate or explain, not even by resorting to a traditional retinue of appropriately luminous metaphors. It was music.

It was music, an abstractly expressive tumult of mind.

___

When I heard Hilary Gardner sing jazz this autumn with pianist Ehud Asherie, I realized again something uncanny: the innate and flowing integrity of her phrasing tempts me to believe that Gardner is the actual author of the songs. The drop-dead beauty of her stylish singing that night left me wondering whether I could have been hearing accurately the confident, mysteriously elastic continuity of slowly rippling lines. Recessional rhythm also counts for a lot in Gardner’s swing, reminding us of how sounds usually come back to the place where they have begun. That’s authority, felt with a grace both palpable and profound.

Graceful I’m not. “What is jazz?” I find myself asking Gardner recklessly at Teresa’s in Brooklyn Heights during a gusty October afternoon.

Graceful I’m not. “What is jazz?” I find myself asking Gardner recklessly at Teresa’s in Brooklyn Heights during a gusty October afternoon.

“I don’t know,” she replies promptly. “I’m not sure,” she corrects herself instantly, with an emphatic shake of shoulders and head.

Of course, that’s the only possible just response. For if she knew what jazz is, then jazz would be over, wouldn’t it?

___

Two summers ago, I first heard Tamar Korn’s ensemble, A Kornucopia, at Barbes in Park Slope, and noted once again Korn’s piercing lucidity and her antic lyricism in scat and more. (More recently, Leonard Cohen has entered her repertoire publicly, with a bracing dignity.)  Even though blues is not her favored genre, Korn’s rendition at my request of “St. Louis Blues” struck me as the single most incorrigibly pure blues singing I have ever heard.

Even though blues is not her favored genre, Korn’s rendition at my request of “St. Louis Blues” struck me as the single most incorrigibly pure blues singing I have ever heard.

She improvises without seeming to try, although she has credited the impulse to painful personal history; her paternal grandparents were imprisoned in a Siberian gulag, and improvisational music represents to her “a Houdini escape.” When the full inventive range of her subtle musical imagination takes possession of a song, it raises again a basic yet neglected question: What is music, anyway, and what might it become?

Korn out-twangs a banjo, out-toots a cornet. She will take a song apart and toss it around with a tickling of tonal moods, delivering a full-throated shake-up of expected phrasing, as if to tease into being a majestic mischief. It’s heartfelt, too.

She compares jazz singing to surfing. “Your center of gravity gives you balance over the constantly moving water. You can’t control the motion of the waves, but you can choose which waves to ride.” The California native has surfed “a few times.”

Still, the provocative image suggested by Korn of herself singing while atop a wave might also come across as jauntily incongruous. Could this be because, in person, she impishly evokes a demure and diminutive version of Betty Boop, probably shy of five feet tall minus Korn’s habitual boots? Dark ringlets cling to her creamy, heart-shaped face. Soon, very soon, she will begin to laugh.

She first learned how to harmonize in singing during Shabbat family dinners. Tadek Korn, her father, was a professional classical violinist. “He was as verbal as a human being could be,” she muses. “Thinking about what you’re saying when you’re singing it: it’s hard to embody the lyric. That requires a certain relaxed composure, and also an intensity of body and heart.” I nearly always find her singing fiercely spritely. When she sings, she smiles.

Still, I hear a sadness in the merriment, because, as I scrawled one August night in my notebook, “Musicians are mysterious to me. They are always transitory. The transition is the place where they live. That place is in between, where no one else can live.”

Ouds and ouds

I’ll admit that Barbes, where the whiskey even now costs only seven dollars a glass, sometimes lets me down—for example, when a band supposedly devoted to the washboard plays hardly any washboard, opting instead for arch faux folksiness of an aggressively smug, annoyingly preening sort. Still, when Barbes curates a truly rare musical event, no one does it better. March of 2016 brought five oud players and their ensembles there in what was billed, justifiably, as an Oud Summit, the second of its kind. The oud, which may sound to American ears rather like a copacetic cross between cello, banjo, and bass fiddle, is closer kin to the lute, but sounds resonantly deeper.

I turned up partly to hear Brooklyn-based oud player Adam Good, hoping that for once he’d take the stage as a soloist. He did not. He played with Jenny Luna and Eylem Basaldi in their trio, Dolunay. But I stayed for five hours because the evening just kept getting wilder and stranger after Dolunay opened it. I changed my mind about a lot, which is my definition of musical time well spent.

For instance, the acoustic oud, which I had preferred, is not necessarily superior. Two, the move toward a musical fusion of seemingly disparate traditions can be exceptionally provocative and exhilarating. Three, a string instrument can also act as a surprisingly powerful mode of percussion, maybe because in oud-playing the plucking hand can tend to punch the melody.

Four, if the strokes of a melody sound unfamiliar, as some oud melodies strike me, then heeding the story they are telling can help. When Mavrothi Kontanis played two drinking songs, one of them an ode to ouzo, I concluded that a just barely blithe version of nostalgic melancholia might be at the heart. Five, it is possible that the phrase “trickling liquidity” can actually describe what the fingers of one hand are doing. They belong to the Canadian oud virtuoso Gordon Grdina, whose taste for enthrallingly rhythmic moments of unison and of caesura enchanted me.

Brian Prunka, who also played at the summit, is a Brooklyn composer whose music, especially when written for the ensemble Sharq Attack, seems more intense, intelligent, and rhythmically engaged than what he plays but does not write. His music also holds onto more energy per cubic inch. Whenever I have the chance, I show up for it in order to learn more about a tradition that’s almost entirely new to me.

What do I hear when I listen to Prunka’s inflected music? The string instruments tend to sound less like instruments than like a human voice, singing under emotional duress. The melodies are almost incredibly beautiful, in part because they frequently attain the state of pure lyric, expressing something that no words ever could. Nothing could correspond in syllables to those sounds; words can’t translate them, either.

The lyric power of this music depends, to a degree, on the music’s refusal to rise and fall adamantly on a melodic scale. (Traditional western music relies on the dynamic of melodic rise and fall.) A melody will hover, then lower a bit, then hover some more, rise, hover, lower, hover, and so on.

This creates a shimmering effect, but the shimmering is earthen. The music sounds neither elevated nor elevating. To me this is what the melody of a human mind would sound like, if untaught and uncorrupted.

Hearing it always leaves me feeling a little more hopeful.

___

Voluptuous pitchers of water, tickled by ice, sit awaiting us. It’s the Zlatne Uste Golden Festival of Balkan music, January 14, 2017, in Park Slope. We’re bound to down what we can. A bar also beckons. This is to be a warm, or warmer, pell-mell kind of evening from 6 pm to 2 am. The place? A Victorian mansion, the Grand Prospect Hall.

There will be crowds—sanguine. There will be sixty bands, give or take, with several thousand of us listening. There will be disembodied ghostly singing. There will be ruckus rhythms that defy analyzing.

Describing Balkan music is, in fact, something of a trial.

Okay, think of a big circle. Then think of all the many points that compose the circle. Think of each point as a moment that can move in almost any way it wants, whenever it wants, commanding motion while receiving motion, in fevered jumps and starts, from the other points alongside of it.

And so, the circle bops, trembles, boogies. At times it folds into itself. At times it subsides just a little, and resurges. Always it’s being redrawn and emended. If I begin to take the circle for granted, that is when its cadences change swiftly. By the way, each point on the circle is a dancer. And please notice: at the center of the circle, a few kids, who don’t yet know the ropes of Balkan music, totter and twirl and hurl themelves to the ground in search of the very rhythms they’re now hearing.

Yes, this annual festival sells out. Few who attend are Balkan. Every age group seems to be well represented. It always reminds me of Canada. No one is rude. NYC has been kicked, dyed, annexed.

Ours is music which drags out the bad things from us, banishing them.

Oh, we’ve got ouds—lots of ouds. And peaceably dissonant all-male or all-female choruses. And Georgian yodeling, by the ensemble Adilei, which reminds me of bagpipes. And Sardinian singing by Tenores de Aterue like the sonorous cries of rocks or ocean swells. (You may ask: why is Italy considered Balkan?) A gypsy violinist named Jesse Kotansky of the Balkan Peppers band sinks swooningly to the floor—or near enough—whenever the bowing compels him.

All I have left to wish for is, maybe, Michelle Dorrance to delve into these infernal rhythms with her unmercifully polyrhythmic tap shoes.

Perhaps next winter?

Strumming and fiddling and running

Gypsy jazz always presents me with a dilemma: is it running away like a rascal as fast as possible from whatever, or is it actually chasing something? The motive for each recoils from the other; they’re mutually opposed. So not only will I remain unable to reconcile them, I will probably never be able to answer my own question.

That helps explain why I keep returning most Sunday nights to hear Stephane Wrembel’s longtime gypsy jazz quartet in Park Slope at Barbes. Here’s another reason: all four are singularly excellent musicians who seem to need what they find together. Their musicality is resplendently consistent. For three hours at a stretch, it never feels like just a gig.

Wrembel narrates with the verbal gavotte of a beatnik holding court, but justly, in a lycée. (Most of us do something altogether different: open the mouth, wait to see what it will say, and then worry afterward.) When he speaks, he sounds like a very concise Proust, calmly translating from his own French. A musician who used to play with Wrembel all the time told me the other evening, “He’s intense. He falls asleep at night while reading Plato.”

Despite superb guitar technique, Wrembel is not about technique foremost, clarified whenever he happens to jam with the unflappable, Finnish-but-he-lives-in-Bushwick gypsy jazz virtuoso Olli Soikkeli. Like a mere blond sculpture made of chilled butter, dapper Soikkeli puts the adjective “nimble’’ recklessly to shame. When I spotted him at Bar Lunatico in Bedford-Stuyvesant last fall listening to the guitarist Julian Lage play a full evening of entirely new, gently genre-bending music, I had to wonder: does Soikkeli mean to take Lage as a model? While Lage played at the Brooklyn Bluegrass Bash of 2016 in Gowanus, courtesy of the Bell House, I marveled at the inventively pure, far-flung musicality of his duo with Chris Eldridge.

Well, forgive the digression. And don’t let’s forget about Stephane Wrembel’s bassist.

For me, bassists are all but impossible to notice. Hulking there, they comment on the main action, providing wry or lugubrious afterthoughts. Wrembel’s bassist is nothing like that.

When he plays, he sways and grabs and frowns and chortles. He’s a maximalist. His name is Ari, and his last name is hyphenated, so better not fuss with that hyphen. Just call him Ari.

One Sunday when some guy was bending my ear while breathing down it, this know-it-all guy said, oh so briskly, to woo me, “That-bass-player-plays-like-a-guitarist. He-plays-as-a-fully-integrated-member-of-this-group.”

I said, “Wait a minute. Wait just a minute. Don’t you notice something else about him?”

I said, “Wait a minute. Wait just a minute. Don’t you notice something else about him?”

The guy, who’d been thumbing his cellphone for thirty minutes, replied, “No-what-is-it?”

“He’s GRAPPLING with his instrument.”

“Oh, grappling!” He glanced up at Ari for two secs. “You’re right. Grappling-is-certainly-the-word-for-it.”

I would put it another way, actually. Ari plays like there is nothing else to play, no before, and no otherwise. (And, by the way, so does Wrembel’s guitarist, when he gets the chance: during January, while Wrembel was away in France, Thor Jensen not only ran away with our ears, but sang, also.)

Even Ari can get quiet. In March of 2017, Wrembel concluded a week-long Django Reinhardt festival by commanding an acoustic-only set from his band and their assorted guests convening at Barbes. The result? Music that sounded shy, whispery, even delicate—including Ari’s ticklish bass mutterings. The usual bluster of gypsy jazz came to a chastened and rustling halt.

On a night without a guy to distract me, I’m able to ask Ari: “When you play, are you dancing with it?”

He says, “Sometimes.” He grins sweetly.

K. Sublime on Court Street

On June 21, longest day of the year, I go looking for a rumored John Cage waltz concert (yes!) in Brooklyn’s Cobble Hill as one of several hundred events presented in the annual one-day Make Music Festival, 2016, New York City chapter.

First comes a swallow of limeade at Sahadi’s as a cure, I hope, for baked forehead. OK, where is Mr. Cage? Scuttling across Atlantic Avenue toward Kane Street, I think I hear something else—an unmistakable peal. It’s like a wailing, thumpety-thump barrelhouse version of Bach’s “Goldberg Variations.” How can that be?

I say wailing because it is unholy loud, barrelhouse because it’s coiling and rhythmic and a little bit ragged. Never mind that waltz.

Have you ever heard “Goldberg”? I learned how to walk from listening, with ignorant care, to Glenn Gould”s early-career piano rendition of it: that somber, methodical quickening and re-quickening of an imagination, and for such a long span, without the sing-along soul-mongering that crept later into his recordings. (I liked that, too, but for other reasons. I’m also very fond of Peter Serkin’s cheekily ethereal version.) I learned to walk, to Bach, in peace, while somebody was ironing. Ironing at our house usually called for Baroque keyboard music, or sometimes for Beethoven, which caused cavorting and shouts, toppled objects, and collisions. Not so good for the ironing board, or for the shirts.

On Court Street in Brooklyn, when I hear the Bach, I begin to trot, then to throw myself at it. This is to be a grueling reunion. In order to cross side streets faster in the clog and welter of quaintly overpriced brownstone rush-hour traffic, I start directing drivers with florid hand gestures. A distant forebear was a Dublin traffic cop, and privately I seek his crotchety blessing.

The “Goldberg” gets louder. Then, unaccountably, the volume plummets and only slinks along. Traipsing in the thick of summer strollers and ice-cream matrons, I almost give up.

Is the Bach really billowing now from a taxicab? From a helicopter? From a garbage truck?

Try not to trip.

At last I notice a musician, K. Sublime, seated in a chair on the curb near Butler Street. Chic black bonnet, flicker of black veil, plump lower lip. And a plug-in keyboard before her. Shoppers, cars, buses, trucks stream past. Bach eddies from the curb.

Near a construction site I prop myself against a pile of bricks. Parents with free-range children pause, smile almost convincingly, hold up cellphone cameras.

When the end of “Goldberg” commences, since I know this is the end, I begin to sob behind my sunglasses. I do that as quietly as I can. After all, Bach wouldn’t want me any louder.

It’s my own kind of music.

Cravings

The kitchen of the Manhattan Inn is now closed.

No more dead chicken, very heavily salted, very briefly fried. No more soggy, morose, hot-and-cold “heated” cornbread squares. No more briny, fuming, sticky “gumbo.” No more waitstaff; none. You can seat yourself, thanks, and fetch your own drinks from the bar. Speaking of seating, all the small tables, once handy for pairs or singles, have vanished forevermore.

Really, it’s not bad news. I no longer have to order anything. In fact, I won’t have to drink a single drink here ever again. After tonight, I will never ever have to wade into the loo at high tide.

Yes, this onetime piano bar in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, is now a whole new operation, except for a single feature, perhaps: that huge old dead plant remains, hanging lavish above the lonely piano, shedding mites in deferential, dusty downpours, doesn’t it?

Since the former house pianists were sent packing, it’s noble of Le Poisson Rouge, noted music club in Greenwich Village, to tiptoe bravely into Greenpoint to present a musical program tonight at the Manhattan Inn. The guest hosts are bent on “bringing music to places outside New York,” they say, meaning outside Manhattan. At their HQ, the cover charge is steep. In Greenpoint, there is no cover charge.

Music will still be music, no matter whose, no matter where, no matter what, just not the same sagely low-down stomps and blues of yesteryear, with affection for the likes of Professor Longhair, “St. James Infirmary,” and Jimmy Yancey tunes.

Tonight the distinguished pianist Taka Kigawa will play at the Manhattan Inn. I’ve come to my old blues haunt to savor the changes management has wrought. (A few months later, the dive will be sold.)

I like Kigawa’s repertoire, heady with experimental music and wisely indebted to the Baroque. In August the faithful were to gather at Le Poisson Rouge to hear him play Chopin and Debussy’s preludes. He played melody by Chopin almost as though it were rhythm; and he played rhythm nearly as if it were melody, avoiding the temptation to board the sashay of the Romantic. The effect was to drain melody of any excess lingering sweetness and to elevate rhythm until it teetered on the brink of effervescence: a paradoxically brilliant and humble stroke.

By chance I was seated adjacent to his wife, a Japanese poet. I asked her what music and writing have in common. She replied, “I think what they have in common is self-expression,” meaning, music and writing give to a practitioner something to express, or a way to express it. When Kigawa played Chopin melody as though it were rhythm and rhythm as if it were melody, was he saying, “This is me, because this is the way I hear that”? By contrast, playing a Debussy prelude may be about navigating transitional moments as if they were the principal constituent structure. To do so invites immaculate tone, like that of Jean-Yves Thibaudet.

Tonight Kigawa carefully tests the piano, which has been “worked on by the Yamaha people,” by picking out a few licks by Bach. Apparently this piano is not much good if you are actually a serious pianist who is playing actual music—not just banging away at whatever just because you can. The piano’s draped in strings of white Christmas lights as of a Monday night in late June 2016.

While he’s playing six preludes back to back, I notice with renewed appreciation that Kigawa doesn’t flinch at dissonance, nor does he exploit the dissonance or put it to work to “say something” for him. That dissonance speaks for itself. Although plenty of musicians go to the piano hoping to write a signature upon it, Kigawa doesn’t seem to be one of those, even though he’s introduced tonight as “a rock star,” someone who can flourish just such a signature. The lack of an assumed signature helps to set him apart. Perhaps he is too fully involved in the moment of the music to inscribe willfully any signature, which might strike a composer as secondary to what the composer had composed. To an extent, Kigawa plays everything as if it were “new music,” without presumptions about what style can be or should mean.

He makes choices without seeming to hesitate or regret, as if he were a piano, and as if nobody needed to play this one, thank you anyway; for, eerily, it can play itself. In his hands the piano can play itself with an unmitigated pragmatism, as if music were invented to answer a daily hunger, a craving.

Not that everything he plays sounds equally original. It doesn’t. Moreover, nothing that he plays sounds cerebral, Romantic, elated, or exquisite. Nor does he play music as if overwhelmed by an instant or two of discovery, with a stubborn, holy prescience. The music played by Kigawa, as he plays it, is like that food we foolishly forgot about, so could no longer crave.

It is the opposite, in other words, of cornbread from the Manhattan Inn.

If we were to crave Kigawa’s music again sometime later on, just because of him, just because of how he plays, just because we once heard him do it, just because he reminds us of why we crave music and of how this feels to us, I’m guessing that the uncommonly modest, incurably honest, pristinely musical Kigawa really wouldn’t like it: impure of us, perhaps?

Well, Brooklyn—too bad.

Purchase MQR 56:1 for $7, or consider a one-year subscription for $25.

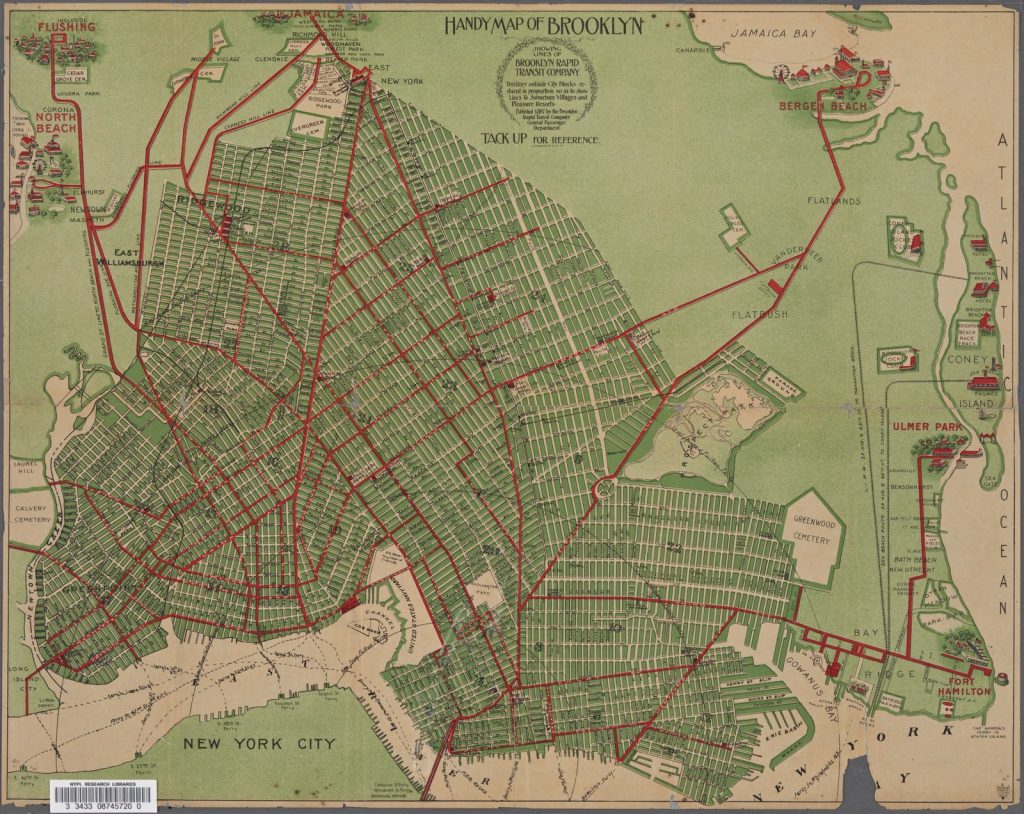

Lead image: Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library. “Handy map of Brooklyn.” New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Inset illustrations by Molly McQuade.