“On Amelia Earhart: The Aviatrix as American Dandy,” an essay by Anne Herrmann, appeared in the Winter 2000 issue of MQR.

i. “These pioneers themselves established the aviator’s image, partly by their idiosyncratic behavior and partly by their own accounts of it. Since many of their activities were by their nature individual and unwitnessed it was unavoidable that this image, to a very great extent, should be self-created.” (David Lance, “Folklore of Aviation,” Journal of the Royal United Services Institute for Defense Studies 21:1, 1976)

ii. “Lindbergh had the world at his feet, and he blushed like a girl!” (Charles Lindbergh, “WE” [1927], 318)

On June 13, 1927, following his successful transatlantic flight from New York to Paris in the Spirit of St. Louis, Charles Lindbergh returned to New York City, to “the greatest welcome any man in history has ever received in terms of numbers.” [1] An estimated three to four and a half million people lined the streets from the Battery to Central Park. Twenty-five thousand extra tons of newsprint were required to publicize the affair; the same year ten thousand poems were submitted to a national contest in commemoration of the feat: “Never in history did an event so brief provoke so many poems in so short a time.” [2] Throngs of people came to see the person who had flown alone. The pilot himself had seen almost nothing, flying “blind” over a body of water through fog, sleet, and nocturnal darkness.

When Lindbergh arrived at City Hall, Mayor Walker delivered a speech not about, but addressed to the hero:

Everybody all over the world, in every language, has been telling you and the world about yourself. You have been told time after time where you were born, where you went to school, and that you have done the supernatural thing of an air flight from New York to Paris. I am satisfied that you have been convinced of it by this time.

And it is not my purpose to reiterate any of the wonderful things that have been so beautifully spoken and written about you and your triumphal ride across the ocean. But while it has become almost axiomatic, it sometimes seems prosaic to refer to you as a great diplomat, because after your superhuman adventure, by your modesty, by your grace, by your gentlemanly American conduct, you have left no doubt of that. But the one thing that occurs to me that has been overlooked in all the observations that have been made of you is that you are a great grammarian, and that you have given added significance and a deeper definition to the word “we.”

We have heard, and we are familiar with, the editorial “we,” but not until you arrived in Paris did we learn of the aeronautical “we.” Now you have given to the world a flying pronoun. [3]

The “flying pronoun” Lindbergh bestows on the world will serve as the title of a memoir he writes under the auspices of the publisher George Palmer Putnam, who understands that the book must reach its public before the story of the flight fades as front-page news. Lindbergh agrees to convey his tale to a journalist who would then retell it in the third person. When the final story is written in the first person under Lindbergh’s name, Lindbergh rejects the ghost-written manuscript, but agrees to write another book. “WE“, completed within three weeks, sells over half a million copies, breaking another record, that of a first-time author.

Lindbergh is unable to complete the story. While providing a narrative that will become the aviator’s standard life history: flying student, barnstormer/wing-walker, flying cadet, air mail pilot, record long-distance flier, etc., he refuses to provide a description of what happened after the flight, claiming a lack of skill as amateur author. (Even though in 1953 he will receive the Pulitzer Prize for his second autobiography, a rewriting of the first, The Spirit of St. Louis.) “I am not an author by profession, and my pen could never express the gratitude which I feel towards the American people,” he writes. “The voyage up the Potomac and to the Monument Grounds in Washington; up the Hudson River and along Broadway; over the Mississippi and to St. Louis—to do justice to these occasions would require a far greater writer than myself.” [4] The hero’s return journey, this time marked by identifable landmarks and scores of firsthand witnesses, is no longer tellable by the solo pilot whose heroism requires, above all, modesty. Fitzhugh Green, a staff writer of Putnam’s, is commissioned to complete the memoir. Entitled “A Little of What the World Thought of Lindbergh,” it largely consists of quotations from politicians’ speeches.

Two intermediary texts facilitate the transition from one author to another. George Putnam writes a “Publisher’s Note” which agrees that “Somehow it wasn’t a story for him to tell”[5]and thus allows the second part of the record to be written in the third person by someone of Lindbergh’s choosing. An “Author’s Note,” followed by Lindbergh’s actual signature, appoints Green, nowhere mentioned on the title page, as additional author, as someone “who has caught the spirit of what I have tried to do for aviation.”[6]

The hyperbolic rhetoric of the politicians’ discourses underscores the modesty of the long-distance flier whose symbolic function is to provide the focus of a mass spectacle while at the same time relinquishing any credit that rightfully belongs to the “American science and genius” that designed and constructed the plane. Green’s role is to interpret the event in world-historical terms by naming it historically unprecedented and thereby inaugurating a “new” age. This age will be characterized by “airmindedness,” a moment between the two world wars when flying evolves from an aristocratic sport into a commercial industry. This requires repressing both its military origins (the “flying ace” whose heroism was marked by the number of enemy planes he shot down) and its origins in popular amusement (the “flying circuses” that developed when discarded military planes were reclaimed by those seeking to earn a living flying). By physically transcending the site of social arrangements through flight, the aviator will assist others in ideologically transcending the symptoms of social disorder: the unprecedented human destruction wrought by aerial bombings of urban populations during World War I, the unchecked industrialization of monopoly capitalism as evidenced by the railroad companies, and the disregard for a Constitutional amendment mandating Prohibition.

While Lindbergh insisted that the title “WE” referred to himself and his backers (the eight men from St. Louis who financed the flight that enabled him to collect the $25,000 prize money), reviewers preferred the meaning given by the ghost-writer who had originally coined the title, namely that the first person plural was the pronoun used by Lindbergh to refer to himself and his plane. The “aeronautical ‘we'” can additionally be read, as I suggest, in terms of a joint authorship necessitated by this particular form of the modernist memoir. On the one hand the memoir relies on syndicated accounts of the flight that have been paid for before take-off by a newspaper editor to increase circulation; on the other hand the first person pronoun lends an air of authenticity to the accomplishment of an individual being publicized for mass consumption. The solo flier was the only one there and thus remains the only one able to tell the tale. At the same time the hero who tells his own story must stay clear of the self-promotion made possible by publicity available through the mass media. Promotion and publicity, necessary to the financing of flights and thus to fueling the profits of an emergent industry, must always be left to someone other than the pilot, thus creating an “authorial we” that replaces the plane of the “aeronautical we” with the function of the publisher/manager.

But the “phenomenon of Lindbergh” is not just about the relation of pilot to public in the arena of the mass spectacle. It is also, as suggested by another passage in the Mayor’s speech, about the reinvention of a notion of nationhood as it was being reconfigured in the 1920s and ’30s through the figure of the flier:

That “we” that you used was perhaps the only word that would have suited the occasion and the great accomplishment that was yours. That all-inclusive word “we” was quite right, because you were not all alone in the solitude of the sky and the sea, because every American heart, from the Atlantic to the Pacific, was beating for you. Every American, every soul throughout the world, was riding with you in spirit, urging you on and cheering you on to the great accomplishment that is yours.

That “we” was a vindication of the courage, of the intelligence, of the confidence and the hopes of Nungesser and Coli, now only alive in the prayers and the hearts of the people of the entire world. That “we” that you coined was well used, because it gave an added significance and additional emphasis to the greatest of any and all ranks, the word of faith, and turned the hearts of all the people of the civilized world to your glorious mother, whose spirit was your spirit, whose confidence was your confidence, and whose pride was your pride; the “we” that includes all that has made the entire world stand and gasp at your great feat, and that “we” also sent out to the world another message and brought happiness to the people of America, and admiration and additional popularity for America and Americans by all the peoples of the European countries. [7]

The mayor of New York, “the world city,” receives Lindbergh, the “world’s greatest hero,” as one son of an immigrant welcoming another. The status of son becomes equated with that of citizen, distinguishing the American from the foreign-born, those in teeming tenements surrounding Settlement houses in the industrial neighborhoods of large cities. President Coolidge, in his welcoming speech, will go so far as to portray Lindbergh as “inspired by the imagination and the spirit of his Viking ancestors,” [8] thereby seeking to remake the country by reinvoking the Northern European immigrant, or Nordic, who will come to represent an unmarked ethnicity and a new masculinity—blond, slim, silent, and, above all, young. By stating further that, “In less than a day and a half he had crossed the ocean over which Columbus had traveled for sixty-nine days and the Pilgrim Fathers for sixty-six days on their way to the New World,” [9] Coolidge refigures the relationship between the Old World and the New by reversing the direction of the journey and by focussing on the difference in speed. Technological superiority on the part of the New World, spearheaded by the aircraft/aerospace and film industries, will manifest itself as a form of reverse colonization, making its appearance in the guise of good will.

Born in 1902, Lindbergh’s age coincides with that of the twentieth century and of heavier-than-air flight, first accomplished by the Wright brothers in 1903. Politicians refer to Lindbergh not only as the son of his mother, thereby foregrounding a normative heterosexuality predicated on the asexuality suggested by his youth, and a son of the people, a Minnesota farm-boy educated at a large state university whose father served in Congress, but as the “new” version of an old-style national hero: “He was a plain citizen dressed in the garments of an everyday man.”[10]An “Ambassador without portfolio,” he attends Swedish churches in European capitals and with heads of state visits cemeteries where the dead of World War I lie buried. If the diplomat has replaced the military general, it is because “airmindedness” is being imagined as a substitute for conflict between air forces in the relations between nations. Aviation from its inception will nevertheless be organized as a national industry, irrefutable evidence of national superiority, while the aviator will serve as prototype for a super-race, beginning with the World War I “flying ace” and culminating in the Luftwaffe of the Nazis, to which Lindbergh will develop sympathetic leanings when he advocates isolationism on the eve of World War II.

Lindbergh’s relation to the two French fliers, not the foreign born but the foreign, Charles Nungesser and Francois Coli, who disappeared during their attempted flight across the Atlantic from east to west while Lindbergh was crossing from west to east, further complicates the meaning of the “aeronautical ‘we.'” On the one hand, they represent the “we” of collaboration in contrast to the individualism of the solitary flier (even as every one person in the air requires nine on the ground); on the other hand they embody the linguistic other that allows Lindbergh to become part of a “we” by speaking of them when others speak only of him. They signify the heroic as constituted through the danger of death, the ocean permanently claiming the “we” of pilot and plane, which in the case of aviation often takes the form of disappearance, without a material trace. Without a body or a grave, the eulogy becomes even more of an imperative. Lindbergh insists repeatedly that what the two fallen heroes attempted was far greater than his own endeavor (headwinds make the flight from east to west longer and more hazardous), thereby undermining the reading of his own success in terms of a national victory. While politicians invoke the achievement in terms of “friendship” between the United States and France, the aviator beckons to other aviators as a way of invoking the tight-knit community of fliers. The “we” of those who have taken to the skies transcends both the individual accomplishments of the solitary pilot and the arbitrariness of national boundaries, especially as seen from the air.

By effacing himself, Lindbergh leaves the meaning of the event, just as he does the meaning of “we,” to someone else, to those who would profit from it, either ideologically, such as politicians, or financially, like newspaper editors and publishers. The aviator, whose historical origins lie with the military hero, will become the celebrity, whose cultural ties will be forged with Hollywood. Putnam himself eventually leaves the publishing house carrying his family’s name to work for Paramount Studios and already in 1927 brings to their attention the book of a World War I pilot instructor that leads to the production of Wings, the first film to win the Academy Award for best picture. Keeping a plane in the air requires as much capital investment as making a movie, but unlike the movie star, the aviator can still claim that the prize money and endorsements are necessary in order to keep flying and that the publicity is for the good of the industry. As Lindbergh is being acclaimed in terms of idealism and authenticity, untempted by money or fame, nicotine or alcohol, the “phenomenon of Lindbergh” points to the artificiality of the construct of the celebrity that eventually exceeds the control of the individual.

When Lindbergh arrives at Le Bourget airport upon successful completion of his flight he takes off his flying helmet and places it on the head of a newspaper correspondent as a way of leaving his identity behind in order to escape the crowds that have carried his body off the ground and dismantled his plane. If Lindbergh released the “greatest torrent of mass emotion ever witnessed in human history” [11] this was partly due to the nature of the accomplishment, but also to the speed with which the news spread and the availability of his physical presence to incite a mass spectacle. What happened spontaneously in the case of Lindbergh will be harnessed with even greater efficiency in the case of Amelia Earhart, by none other than George Putnam, so that the same mayor of New York will be able to say five years later: “Five years ago we believed that the aeronautical ‘We’ had but one gender; now you’ve destroyed that. The Atlantic solo has gone co-ed.”[12]

iii. “This coming conquest of the air offers an absolutely new element in progression; we enter, as it were, the third dimension. . . . The introduction of a new medium of communication which will throw all mankind together so much more freely carries with it the necesssity for a general rising of standards. When it becomes possible for rude or dangerous persons to flutter to our windows by night and day, we must simply see to it that there are no rude or dangerous persons.” (Charlotte Perkins Gilman, “When We Fly: How the Accomplishment of Aerial Navigation Will Make Necessary a Revision of Human Laws and Customs,” Harper’s, November 9, 1907).

iv. “The woman at the wash-tub, the sewing-machine, the office-desk, and the typewriter can glance up from the window when she hears the rhythmic hum of a motor overhead, and say ‘If it’s a woman she is helping free me, too!’. . . . In some strange way aviation is a door through which one may enter a new dimension.” (Margery Brown, “Flying is Changing Women,” Pictorial Review, June, 1930)

Amelia Earhart begins her career as aviatrix in the role of guest of the Honorable Mrs. Frederick Guest of London, formerly Miss Amy Phipps of Pittsburgh, wife of the Right Honorable Frederick Guest, member of Parliament, international polo player, and former British Air Minister. Mrs. Guest leases a tri-motored Fokker considered unsuitable by Commander Byrd for an expedition to the Antarctic in the hope of being the first of her sex to fly across the Atlantic. She names the plane the Friendship as a way of fostering Anglo-American relations, represented by her own marriage between the British aristocracy and American industry. For “personal reasons” (her son phoned from Yale University saying he would leave college if she boarded the plane), she is unable to fly herself and, fearful that the first woman might be Miss Mabel “Mibs” Boll—a wealthy woman of questionable reputation known as the “Diamond Queen”—she commissions George Putnam, who has already made himself manager of the expedition, to search for a suitable substitute. She stipulates that the person be a woman and an American, and some speculate that she specifically suggests a ressemblance to “Lucky Lindy.” According to one biographer: “She should be a pilot and well educated; preferably a college graduate. She should be physically attractive and have manners that would be acceptable to members of English society, who would undoubtably welcome her on her arrival there.” [13] Guest herself did not meet at least one of these criteria: she did not know how to fly. Photographs show her to cut the figure of a plump society matron. She nevertheless intends that the first of her sex will be a “lady” rather than a nightclub hostess, not an “Ambassador without portfolio,” but of “true womanhood.” Putnam assigns Hilton H. Railey, New York Times correspondent, to place a call to a Settlement worker at Denison House in Boston, a “social worker who flies,” named Amelia Earhart. The “right kind of girl” turns out to be “a tall, slender, boyish-looking young woman,” [14] in the words of Marion Perkins, Head Worker at Denison, where Earhart directed the evening school for foreign-born men and women. The resemblance to Lindbergh is unmistakable and Earhart acquires the nickname she will never be able to shed, “Lady Lindy.” [15]

Railey claims: “Her resemblance to Colonel Lindbergh was extraordinary. Most of all I was impressed by the poise of her boyish figure. Mrs. Guest had stipulated the person to whom she would yield must be ‘representative’ of American women. In Amelia Earhart I saw not only their norm but their sublimation.” [16] Other journalists are less generous. One even goes so far as to suggest that regardless of whatever natural resemblance there might have been, her image was intentionally exploited to simulate his: “By manipulation of pictures and publicity, Amelia Earhart, the Boston girl who is crossing the Atlantic with Wilmer Stultz, is to be made a feminine Lindbergh, unless plans go awry. The stunt is financed by George Palmer Putnam, publisher of WE who now plans a similar book, it is understood, called She. . . . Amelia Earhart has been in training, coached by the promoters, to emulate Lindbergh in every respect, in attitude, pictures and behavior.”

Unlike Lindbergh, who resists being positioned as lone pioneer by invoking a brotherhood of fliers, Earhart functions as the copy of an image already in circulation. While Lindbergh represents the American citizen as common man who has demonstrated national superiority vis-à-vis the French, Earhart represents “the American girl” in contrast to the “Diamond Queen,” the society woman who fails to launder her self-procured millions by marrying into the British aristocracy. The regendering of the aviator requires that sporting adventures not be confused with sexual ones. If what they share is a modesty characterized by an unwillingness to engage in self-promotion, Lindbergh will attempt to retain that image by seeking the normalcy of private life and steady employment in the airline industry (temporarily interrupted by the kidnapping and slaying of his first child), while Earhart will displace that image onto the promotion of her sex, supplementing personal adventure with a sense of social obligation. Her eventual marriage to George Putnam will forge an even more powerful “we” than the aeronautical one in that the “marital we” will allow Putnam to devote himself full-time to her promotion. The solo flight across the Atlantic that Lindbergh accomplished at twenty-five, Earhart will accomplish at thirty-five, her boyishness not tied to her youth, but to her slacks and short hair. Whether accidental or intentional, Earhart managed to keep that image in the public eye for nine years, an extraordinary length of time for a celebrity image based on record-breaking events, yet no time at all given the longevity of her legend.

Where and how she received the famous phone call that launched her career as aviatrix will be retold in each of her memoirs, 20 Hrs 40 Mins (1928), For the FunOf It (1932), and The Last Flight (1937), as well as in an article written for American Magazine entitled “Flying the Atlantic—and selling sausages have a lot of things in common” (1932). She was called to the phone one afternoon at work, surrounded by Chinese and Syrian neighborhood children. When asked whether “she would do something for aviation that might be hazardous,” she first thought it was a joke and then asked for references. Ten days later she had an interview in New York with David T. Layman (New York attorney), John S. Phipps, and George P. Putnam, although in the final version she suggests that Railey, unimpressed with her, almost prevented her from appearing in front of this “masculine jury.” Faced with a positive verdict, she could of course not say no: “When one is offered such a tremendous adventure it would be too inartistic to refuse.” [17]

How she assesses her own position is worth quoting in all its variations. Initially she writes:

It should have been slightly embarrassing, for if I were found wanting on too many counts I should be deprived of a trip. On the other hand, if I were just too fascinating the gallant gentleman might be loath to drown me. Anyone should see the meeting was a crisis. [18]

In “Flying the Atlantic” she writes:

If they did not like me at all, or if they found me wanting in too many respects, I would be deprived of the trip. But if they liked me too well, they might be loath to drown me. It was therefore necessary for me to maintain an attitude of impenetrable mediocrity. Apparently I did, because I was chosen.[19]

And finally in the third version she begins: “The candidate, I gathered, should be a flyer herself, with social graces, education, charm and, perchance, pulchritude.” She then adds:

It should have been slightly embarrassing, for if I were found wanting in too many ways I would be counted out. On the other hand, if I were just too fascinating, the gallant gentleman might be loath to risk drowning me. Anyone could see the meeting was a crisis. [20]

The crisis requiring resolution has less to do with Earhart herself than with the gendering of the interview situation. A group of men seem to be deciding the fate of a particular woman when what they are actually doing is reinforcing “woman” as marked category: a single individual represents the entire sex; a single casualty would produce its symbolic demise. The double bind has an apocalyptic ring in that the two options Earhart presents are deprivation or drowning, loss of opportunity or loss of life, the latter being the price of heroism denied women as a sex. Would she be deprived of a trip or the trip? Are they going to drown her or risk drowning her? Does being found wanting mean not being fascinating enough or not being liked? How will this dilemma be solved? Earhart seems to provide two solutions: either one has the qualities they are looking for—”social graces, education, charm, pulchritude”—or one has no qualities and remains “impenetrable.” While each retelling is accompanied by greater insight into the stakes at hand, Earhart fails to make explicit the extent to which these represent two sides of the same image: by representing a type, no one will ever wonder who she is. To be “the American girl” is to be mediocre in the sense of ordinary, middle-class, a girl not a woman, and above all, white.

Bessie Coleman, the best-known black aviator of the era, likewise befriended (rather than being befriended by) a newspaper editor, Robert Abbott of the Chicago Defender, who also promoted her image to increase circulation. Unlike Lindbergh, whose arrival in Paris promoted “friendship” between two nations, Coleman was forced to travel to France to obtain her pilot’s license, since flying schools in the United States maintained a color bar. Unlike Earhart, whose husband doubled as business partner, Coleman married an older man she never shared an address with and became known as “difficult” when she broke with a string of (male) managers. An impoverished migrant from the South, there was no place for a manicurist turned pilot in Chicago’s black society, just as there were no women in the pilot’s union or black women in the first organization for women pilots. While her relationship to the public was almost exclusively mediated by the black press, promoting the first flying school for Negroes required a degree of self-promotion that crossed the fine line between publicity and falsification to become a marker of racial difference. Her need for self-promotion has led her biographer to characterize her seeming lack of modesty as a sign of “self-dramatization,” created by “her good looks, her sense of theater, and her eloquence.” [21] These included performing impressions of other nationalities, handing out press releases about her accomplishments and actual misinformation (particularly about her age). In a book dedicated to Coleman entitled Black Wings (1934), William J. Powell imagines aviation as an emergent industry where blacks could own businesses, like Jews, by hiring their own, and the air would offer a form of transportation that knew no color line, unlike railroad cars and buses segregated by Jim Crow laws. But unlike Earhart, who disappeared during her last flight, Coleman died at thirty-four by falling out of an exhibition plane piloted by a young, white, male flier. Memorialized by Powell’s dedication, a marked grave on the South Side of Chicago on which flowers are dropped yearly (and a road recently renamed for her on the way to O’Hare Airport), Coleman left no memoir, having learned to speak French without having mastered the rules of English grammar, the sign of a subject who was unable to forge a legitimizing “we” for reasons of race, gender, and sexual “queerness.”

v. “The girl in brown, who walks alone.”

Unlike Lindbergh who refuses to finish his tale, Earhart retells the same story several times. It is not her tale that lacks completion but her identity that enacts a contradiction. The “authorial we” reverts back to the “aeronautical we,” but this time regendered, not as pilot and plane, but as woman pilot and all other women. Earhart’s memoirs resist a developmental model of autobiographical discourse by each time returning to the beginning. This reliance on repetition is partly due to their production status as “instant” books and partly the consequence of a topical rather than chronological sequence characteristic of the memoirs written by Progressive era social reformers. “Instant” or “fabricated books” was a genre invented by Putnam, who thought of an idea for a book and then went in search of its author. The book needed to appear in bookstores before the author’s name disappeared from the headlines in an attempt to diminish the time lag between newspaper and book publishing. Offering what the newspaper account could not, namely an adventure story written in the first person, the prototypes for such a system of authorship were Commander Richard E. Byrd’s Skyward (1926), about the first flight over the North Pole, and Lindbergh’s “WE“. For Earhart, who was expected to do this more than once in her lifetime, more and more material had to be written before or during the flight and/or recyled from previous writings. 20 Hrs 40 Mins was finished August 25 and in the bookstores by September 10, having been written at Putnam’s home in Rye, New York, where he provided the space and necessary solitude. The last chapter of For the Fun Of It was added after Earhart’s solo flight across the Atlantic in 1932 and Last Flight appeared posthumously and heavily edited by Putnam, based on the 30,000 words she wrote before her disappearance over the Pacific. Not only were first editions of For the Fun Of It sold with a record attached of a radio speech she delivered over transatlantic radio, but a year later she would write “Part of the Fun Of It” for Home and Garden (April, 1933), a two-page advertisement which passed itself off as a first person narrative, endorsing Kodak cameras and film.

The autobiographies written by those engaged in Progressive era reform movements likewise resist the individual life history by including personal anecdotes only to help explain the etiology and evolution of the exceptional woman. Topical headings replace historical chronology in order to allow for the embedding of intertextual documents into a genre that seeks to identify itself, at least partially, with the sociological report. [22] Jane Addams’s Twenty Years at Hull House (1910), the best known example, is more the story of Hull House, the original Settlement House in the United States, than the story of its founder. With her own professional origins tied to the Settlement movement, Earhart nevertheless expands the genre in order to construct her own role in aviation as a form of Settlement work, but also in order to provide a kind of “advice” book, whose origins lie in women’s magazines. She instructs women on how to become pilots as well as workers in the aviation industry, what shortcomings they need to overcome, what social barriers stand in their way. For the Fun Of It has chapter titles such as “Aviation as it Is,” “Women and Aviation,” “Some Feminine Flyers,” and “The First Women Aeronauts,” and includes diagrams of an instrument panel and flying maneuvers.

Recent biographers, such as Doris Rich and Susan Ware, have dismissed these texts with statements such as: “In spite of brisk sales and generally flattering reviews, the book [20 Hrs 40 Mins] was not very interesting. Other than entries from Amelia’s diary, it was a dull summary of the problems of commercial aviation and a plea for more support from the government and the public.” [23] Or, “In general Earhart’s prose was pedestrian and lacking in drama. The books, already printed in very large type and illustrated by many photographs (often the best part), seemed padded with extraneous chapters and recycled material.” [24] It is precisely their lack of conformity to the literary memoir that provides their cultural interest, offering a different relationship between writing and flying than that provided by the male homosocial airline La Ligne that produced the poetic prose of Saint-Exupéry in works such as Night Flight (1931) or the division of labor between flying and writing, husband and wife, that led to the lyrical musings of Anne Morrow Lindbergh: “Was I a modern woman? I flew a modern airplane and used a modern radio but not as a modern woman’s career, only as wife of a modern man.” [25] Earhart doesn’t consider herself a writer and writes for a predominantly female audience. She writes books, magazine articles, syndicated newspaper columns, and answers to fan mail, the latter being her preferred activity. She is not writing for posterity, but for the future, when the plane will be as common as the automobile, itself a recent invention. She is not writing as representative of an age, but as role model for a new age, when women will be more like men, and men like women. The entrance into a profession not yet regulated requires, on the one hand, a reliance on personal experience that resists personal revelation and, on the other hand, a preoccupation with self-creation that foregrounds the image, and thus clothes. Earhart as a woman seeks to reproduce herself in other women, by disseminating information about aviation in a way that normalizes her identity as aviatrix in order to eventually make it obsolete.

vi. “A social worker on a bat.”

Amelia Earhart is the first woman to fly across the Atlantic; three women have died in previous attempts. She is also the first “airwoman,” meaning she knows how to fly although she never takes the controls due to poor weather conditions requiring “blind” or instrument flying, in which Earhart has no training. In 1932 she will become the first person to fly across the Atlantic twice. But in 1928 she flies as a replacement for Mrs. Guest. She flies as a look-alike of Lindbergh. And she flies as a passenger, not a pilot.

The only identity she is able to claim with any authenticity is that of social worker. Not only does she avoid self-promotion by insisting that her entrance into aviation occurred purely by chance, but she also attempts to direct publicity away from herself to where it is rightfully due, with pilot Wilmer (“Bill”) Stultz and mechanic Lou (“Slim”) Gordon. She begins by claiming that the flight was simply something she did during her vacation from Denison and that her purpose was to bring “a message of good-will and friendship from American to British Settlement Houses.” [26] While Stultz and Gordon, “like old war buddies,” drift about town and visit Croydon Airdome, Earhart remains the captive guest of Mrs. Frederick Guest, at whose dinners she meets, among others, Lady Astor, the first female member of Parliament, and Lady Heath, the first woman to fly from Cape Town to London. Unlike other aviatrixes who either made the flying costume itself into a fashion statement (most notably, Harriet Quimby’s purple satin bloomers) or immediately applied make-up upon arrival and packed an evening dress for the reception (Jacqueline Cochran, who developed her own cosmetics line), Earhart chose to take with her only what she had on. Mrs. Guest nevertheless greets her with a traveling case of Parisian gowns so that “donning a frock and other feminine attire for the first time in days,” a reporter comments, she “was suddenly and miraculously transformed from a daring celebrated aviatrix to a typical, nice American girl having a celebration abroad with a party of friends from home.” [27]

The first-person narratives that appear on the front pages of the New York Times between June 19 and 22, 1928, begin as part of a public record that attempts to negotiate between a personal response and an international performance, between “the American girl” and the “public person,” by recreating the aviatrix as social worker. Although Earhart keeps a logbook and knows she is writing news, the nature of the adventure does not lend itself to the pure description characteristic of travel writing: it was uncomfortable, there was nothing to see, she never took the controls. The value of the adventure lies not in what can be described but in the fact that it took place at all: “It is all too recent, this flight, for me to compose my exact impressions or even to remember exactly what happened and when. But I know I would not have missed it for anything.” [28] At the same time she resists the notion of “instant meaning” by refusing an identity that would follow from complete identification with the event: “I am sure I do not want to be known always merely as the first woman to fly the Atlantic. Aviation is a great thing, but it cannot fill one’s life completely.” [29] By making her what she calls a “public person,” the event threatens to turn her into a static image: “Today I have been receiving offers to go on stage, appear in the movies, and to accept numerous gifts ranging from an automobile to a husband. The usual letters of criticism and threats which I have always read celebrities receive have also arrived. And I am caught in a situation where very little of me is free. I am being moved instead of moving.” [30] In contrast to Lindbergh who leaves the field to the newspaper correspondent and retreats from the public eye, Earhart appropriates public discourse by, on the one hand, making an extraordinary event ordinary (she, after all, did nothing), and on the other hand, by normalizing the female flier (she, after all, wore what she always wears). The first she does by promoting aviation as a form of social work; the second by insisting on the importance of the relationship between aviation and clothes.

On the second day, when she attempts to address “what this flight means,” she begins with the observation that the mayor who greets her in Southhampton, the first woman sheriff in England, is addressed as “Mister Mayor,” pointing to the modern woman as oxymoron. She then considers the flight’s meaning for aviation, for women, and for herself, always the order in which she will consider the importance of any aeronautical achievement. The meaning for aviation lies in the fact that future, i.e., regularly scheduled transoceanic flights, are best undertaken by multi-engined rather than single-engined planes, and by sea rather than land planes. For women its importance lies in the fact that it should increase their interest in aviation and thus augment their influence on men, convincing them that flying is safe and therefore should become more comfortable, comparable to the transportation provided by steamers or Pullman cars. And finally the meaning for Earhart herself is not a personal one. She claims it decreases her isolation as aviatrix, and thus as celebrity, by giving her the opportunity to discuss flying as a sport and by the fact that women in England have greater access to light planes through the proliferation of flying clubs. By making flying more ordinary, by making female fliers more normal, her ultimate, and most personal goal is to make herself more the norm and thus increase the number of women like her: “I am lonesome for the companionship of women in aviation. . . . When I want to ‘talk shop’ in aviation at home there are only men to talk to. Bill, Slim and some other flying men I have met are wonderful, but once in a while one likes to talk about a common interest with a woman.” [31]

One way in which she continues the conversation with other women is as aviation editor of Cosmopolitan magazine (after McCall’s drops her when she endorses Lucky Strike cigarettes, even though she herself does not smoke and only agrees to the ad to raise funds for Stultz and Gordon when the endorser refuses to make the ad without her). She writes ten articles between November 1928 and November 1929, each one ending with a reminder to its readers that any questions received will be answered by the author. The editor of the magazine is chiefly concerned with keeping his readers informed, equating “airmindedness” with not becoming “old-fashioned”: “For flying is so much a part of life today that whether or not one wishes actually to fly one owes to oneself an intelligent well-informed interest in the subject.” [32] For the aviatrix, having other women to talk to requires either educating them in the fundamentals of aviation or addressing their concerns as women, as defined by the woman’s magazine. The first approach requires getting women into the air, thus the title of her first article, “Try flying yourself!” The second relies on maintaining feminine attributes but relegating them to a new social sphere, in this particular case, that of “aerial housekeeping.”

Earhart encourages women to enter the air in two ways: by treating flying as a sport easily accessible through clubs (the European model) and by comparing the plane to the automobile, which began as a sport and then became a means of transportation (the American model). She not only offers tips on how to seek instruction, “Here is How Fannie Hurst Could Learn to Fly,” but on how not to prevent others from seeking it (“Shall You Let Your Daughter Fly?”) by admonishing mothers, “Don’t Say ‘Don’t!'” At the same time she encourages women to become passengers, so air travel will increase in volume and increase in comfort, thereby attracting more (female) passengers. Becoming either a pilot or a passenger involves overcoming a fear of flying which stems both from lack of personal experience (feminine knowledge) and lack of access to technical knowledge (male experience): “My point is that aviation is being sold to boys much more effectively than it is to girls.”[33] Girls, for instance, are barred from participating in airplane model contests by stipulating that eligible contestants need to be members of manual-training and shop classes. Here the attempt is to make girls more like boys. The alternative is to let girls be girls. Domesticating the airline industry means encouraging women to find employment in such a way that their domestic skills enhance the public arena: “I foresee that women will shortly become tea-room managers at airports, perhaps traffic managers, perhaps engineers in various branches, and I hope also as designers of the interiors of cabin planes—to mention only a few possibilities.”[34]The aviatrix thus tries to have it both ways: women flying, which is what men do; women in aviation, doing what women have always done.

The double bind that Earhart first articulates in the passage about how she was chosen for the Friendship flight can be recapitulated as follows. If a woman does something ordinary, like becoming a passenger, anyone can do it, i.e., flying is safe. If a woman does something extraordinary, like fly the Atlantic, it will become news, which still means it could either promote the industry or be written off as a publicity stunt. If a woman proves she can do it, i.e., breaks a flying record, she will be rewarded with a place in the industry, although even as a pilot she will most likely be relegated to public relations. If a woman fails to do it, i.e., crashes, the fact of her sex will make it even bigger news, so big that women might even be prevented from flying. This was the case in France when after the deaths of several female fliers women were barred from flying schools, such as the one that Bessie Coleman first sought to attend.

Joseph Corn in The Winged Gospel makes a plausible historical argument when he writes that once “the public’s fear of flying was no longer economically significant. . . . the males who built the planes and ran the industry had no further business need to recruit women pilots as part of a strategy to sell flying to an airminded but timid public” [35] and women were out of a job, except as flight attendants. A narrative of progress might argue that because something does not require physical strength, like flying a plane, or because performance can be measured with mathematical precision, like speed, altitude and long-distance records, gender differences, and thereby gender bias, will be eliminated. But neither Corn’s historical argument nor the narrative of historical progress succeeds in explaining how gender functions as double bind within something like aviation history.

Aviation, in its short history between the first and second world wars, offers in miniature a pattern that recurs repeatedly in the history of women’s emancipation, that is, the narrative of her emergence into modernity. For example, Earhart fought to establish separate women’s flying records because women, lacking training and experience, were not as good as men, and therefore there would be no record of them having flown at all. Once women’s records were established, women caught up with and even surpassed men’s performances. When the records were again combined, since they were now deemed unnecessary, women once more disappeared, partly because there are always fewer female fliers and partly because men now had access to higher performance aircraft. Women are regendered masculine to promote an industry by regendering it as feminine so that in the end all but the exceptional woman will find employment only at its margins. While Settlement work no longer required the regendering of the female subject, aviation still did. And while the Settlement House distinguished itself from both the church and labor unions by “interpreting democracy in social terms,” [36] the contradiction between women flying and women in aviation was not one that could be resolved by invoking a humanitarian ideal.

Earhart’s writing, in its repetition and topical organization, reenacts this conundrum. When asked “to discuss aviation periodically in the magazine from my own experience and point of view,” [37] she is relying on an experience not only she has had. She writes that, “Tabloided my autobiography is simple”: her father’s law work was connected with the railroads, which meant they moved a lot; she became a nurse’s aide to help the war effort, began studying medicine at Columbia, learned to fly and turned to Settlement work. It is nevertheless a life history that can never be replicated. Unlike the predictable trajectory of an aviator such as Lindbergh, Earhart will use her exceptional position as a way of trying to make it more normative.

vii. “But you don’t look like an aviatrix. You have long hair.”

Once Earhart has established the position of the aviatrix as social worker, she further normalizes the female flier through clothes. She does this, on the one hand, by insisting on the history of clothes within aviation, that “‘flying clothes’—fleece or fur-lined overalls of either leather or heavy cloth” [38] are obsolete given the fact that planes now have closed cockpits; on the other hand, by comparing flying to driving a car, which also once needed special clothes but not anymore. The insistence on the suitability of ordinary clothes emphasizes both that women don’t have to look like men, i.e., unsexed and thus unfashionable, nor do they need to belong to a particular social class, engaging in extra expense by buying special sporting clothes. But most important, by wearing street clothes a woman does not have to look like an “aviatrix” and assume that identity in order to fly. But who is this “aviatrix”? What it means to look like a female aviator relies both on being taken seriously on the airfield and on posing as a modern woman. While Earhart herself insists on the normativeness of the female flier, she at the same time creates the most recognizable image of the aviatrix, one that continues to circulate in its postmodern appropriations, including Apple computer ads.

An anecdote recounted in Putnam’s biography, Soaring Wings (1939), serves to illustrate Earhart’s early investment in her look. In 1922 she buys a patent leather coat: “‘But suddenly I saw that it looked too new. How were people to think I was a flier if I was wearing a flying coat that was brand-new. Wrinkles! That was it. There just had to be some wrinkles. So—I slept in it for three nights to give my coat a properly veteran appearance. When I decided not to go to bed in it any longer, I did give it a last going over—rubbing the sheen off here and there.'”[39] How can one be a flier if one doesn’t look the part; how can one look the part if the coat doesn’t look like it already belongs to someone who is a flier?

Responding to one of the two most frequently asked questions: “What did you wear?” (the other was “Were you afraid?”) following the Friendship flight, she writes:

Just my old flying clothes, comfortably, if not elegantly, battered and worn. High laced boots, brown broadcloth breeks, white silk blouse with a red necktie (rather antiquated!) and a companionably ancient leather coat, rather long, with plenty of pockets and a snug buttoning collar. A homely brown sweater accompanied it. A light leather flying helmet and goggles completed the picture, such as it was. A single elegance was a brown and white silk scarf. [40]

The necktie, its “antiquatedness” an allusion to those worn by turn-of-the-century reformers and suffragettes (as well as androgynes), will eventually be replaced by the silk scarf, transformed from a “single elegance” into a necessary sign. The leather coat, made to look “companionably ancient,” will in 1932 be shortened to a jacket. “Breeks” or jodhpurs, reminiscent of flying’s relationship to sport and sports clothes’ origins in the riding habit, will give way to slacks. And the flying helmet and goggles, the aviator’s signature, will be discarded to display the short, unruly hair that marks Earhart as aviatrix.

But once again, like the relationship between books, syndicated columns and endorsements, Earhart’s look becomes a composite of body shape, public image and “queer” identity. She not only considers comfort and safety by wearing slacks and sensible shoes, but she also designs and models a line of dresses that integrates techniques from airplane manufacturing. [41] She not only wears dresses to prove that female fliers are ordinary women, but she wears them of a certain length, so that, like slacks, they hide her too thick thighs. She agrees to follow Putnam’s advice that she smile with her mouth closed in order to hide the space between her two front teeth and complains of her complexion, the skin on her sun-burned face often peeling. But most importantly she agrees to discard the hats that Putnam calls “a public menace” and thereby reveal the tousled blond hair that becomes her signature, even though the curls are not natural. Unlike Lindbergh who escapes identification by placing his helmet onto another head, Earhart retains anonymity only by covering her hair with a cap. While Earhart herself prefers the studio photographs that combine the flier’s helmet with a string of pearls or a velvet evening gown decorated with both pearls and wings, she will be remembered for the leather jacket, silk blouse, and tie.

viii. “I believe you’ve fallen in love,—yes, and his name’s Airplane.”

The boyish look that Earhart retains until her disappearance three weeks before her fortieth birthday produces a non-normative relationship to both masculine gender identity and lesbian sexual identity. This is in part produced by the confusion between the two categories, first established by nineteenth-century sexologists whose notion of the “sexual invert” equated homosexuality with gender inversion so that female same-sex object choice was the result of, for instance, “being a man trapped in a woman’s body.” But this confusion seems to persist among recent feminist scholars. On the one hand, Rich tries to imagine the expectations of Earhart’s audiences, and in the process projects her own anxieties backwards: “If anyone came expecting a coarse or odd person, perhaps even a lesbian (what sort of a woman would challenge an ocean and suggest that other women become aviators?), they were disappointed.”[42]On the other hand, the fact that Earhart shared certain fashion items with historical lesbians of the 1920s, requires provisos such as Ware’s:

Amelia bore no resemblance to the stereotyped figure of the upper-class mannish lesbian, which was common in bohemian circles like Paris’s Left Bank, New York’s Greenwich Village, Harlem and occasionally in Hollywood. These lesbians dressed in tuxedoes and adopted such male affectations as top hats, cigarette holders, and monocles, a style which was foreign to A.E. Nor did she affect the style of working-class lesbians, with their exaggerated role divisions (and corresponding clothes vocabulary) of butch and femme. [43]

In both cases we have what Terry Castle in The Apparitional Lesbian calls “the ghosting of the lesbian,” that is “an effort to derealize the threat of lesbianism by associating it with the apparitional.” [44] In the first instance, she literally fails to appear, contrary to audience expectation. In the second, she appears as stereotype and in no way looks like Amelia. To invoke the lesbian only to dismiss her is in itself a “queer” gesture. What then is “queer”about Amelia?

Earhart was married, but unlike Eleanor Roosevelt, is not rumored to have been pursued by or interested in members of her own sex. At the same time, as Ware rightly suggests, “she was rarely, if ever, presented as a sex object or as exuding any kind of heterosexual attraction.” [45] Rather than imagining the possibility of same-sex attraction, Ware solves this contradiction by resorting to the concept of “gender-blending” as one that reconciles both “a hint of manliness at the very heart of a feminine presence” and “an acceptance of sexual difference combined with a refusal of sexist inequalities,” what other critics have written about Greta Garbo and Katherine Hepburn, respectively. [46] But inasmuch as the aviatrix and the “cross-dressed” movie actress have certain characteristics in common, a female pilot’s only role is to play herself.

The aviatrix embodies neither married motherhood nor celibate, societal motherhood. Earhart is married but childless; as a former social worker and advocate of women in aviation, she nevertheless insists that most of her flying is “for the fun of it,” not for social or scientific progress. As a married woman she retained her name, and agreed to marry George Putnam only under the conditions outlined in a pre-nuptial agreement. [47] While the companionate marriage has been both praised and blamed for her commodification, it nevertheless contradicted the normative model which was that of “Mr. and Mrs. Pilot,” true for female fliers who either married their flight instructors, or like Anne Morrow Lindbergh, learned to fly from their husbands. In contrast, Amelia and her husband managed their joint property “Amelia Earhart” and Earhart agreed to this arrangement because it guaranteed regular solo flying. The “marital we” never compromises the “aeronautical we” of pilot and plane, even as Rich argues that the failure of the last flight can be attributed to a failing marriage.

She had short hair. She flew alone. She did it all “for the fun of it.” Earhart represented an alternative to both the decadence of the heterosexualized flapper of the 1920s and biological motherhood as it was appropriated by the fascists in the 1930s. Ware positions her as representative of post-suffrage feminism, the missing link between the “first” and “second wave” of the twentieth-century women’s movement, a generation marked by the liberal individualism and optimism of exceptional women who served as inspirational role models but found it difficult to institutionalize their success. Earhart wears pants not just to fly, required by the relationship to a machine such as the airplane that makes long skirts a safety issue, but also on the street: “It is possible that the advance of trousers for women is the most significant fashion change of the twentieth century.” [48] She leaves the wearing of the suit to Putnam, so that her boyishness is reinforced by the slacks’ connotation of sport and leisure, but also by a stunted masculinity. Yet she continues to benefit from and furthers the single sex organizations that characterized the same-sex environments of the Progressive era reformers: she insists on learning to fly from a female pilot, Neta Snook; the Friendship is organized and financed by a woman, Mrs. Guest; in 1930 Earhart founds and serves as president of the first organization for female pilots, the 99’s; she becomes consultant in the department for the study of careers for women at Purdue University beginning in 1935.

Just as keeping her own name in a childless marriage signifies a non-reproductive sexuality, “for the fun of it” becomes emblematic of non-productive work. By associating adventure with art, she divorces it from remuneration or social obligation, as required by the image of “the American girl”: “What I am trying to work toward is this: that beauty and adventure have a certain value of their own, which canbe weighed only in spiritual scales. I have the greatest respect for dollars and cents. They are quite important. They pay the rent and the grocer; they buy clothes and satisfy the tax collector. But they are not the final measure of the human spirit.” [49] By advocating for women’s right to physical adventure, she restates her commitment to women’s right to endanger their own lives, not just improve the lives of others. She also insists that what she does is something that does not require monetary compensation.

These traits have traditionally been associated with the figure of the dandy: “The role of the dandy implied an intense preoccupation with self and self-presentation; image was everything, and the dandy a man who often had no family, no calling, apparently no sexual life, no visible means of financial support. He was the very archetype of the new urban man who came from nowhere and for whom appearance was reality.” [50] Post-dating the dandy as historical subject, the aviatrix can be read as his successor in an American form inasmuch as she is constructed by her clothes and aestheticizes not flânerie but flying.

The aviatrix is less preoccupied with creating her image than with selling it, and maintaining its marketability. On the one hand this involves keeping grueling lecture schedules and making endless appearances for endorsements; on the other hand it means reinvesting all profits into future flights that simply perpetuate the cycle. The aristocratic origins of the dandy have been replaced by the commercial demands of the flier. The aviatrix engages in the luxury of long-distance flying during the Depression and she flies alone, both contributing to her glamour. She enters the male-dominated field of aviation yet insists on the company of her sex. A flâneuse of the air, she will never be confused with a streetwalker; a solo flier, she cannot be suspected of sexual desire. Neither tomboy nor butch, neither masculinized nor sexualized, the “queer” property of “A.E.” is one that nobody owns even as it continues to generate instant recognition.

ix. “Defense Secretary Les Aspin this week will order the military to drop most of its restrictions on women in aerial and naval combat, senior Pentagon officials said today. Mr. Aspin is expected to issue a directive on Thursday ordering the armed services to let women fly aircraft in combat. The administration will ask Congress to repeal a law barring women from serving on many warships. Finally, each service will be directed to justify all remaining jobs that are off limits to women, including service in ground combat units.” (New York Times, April 28, 1993)

x. “Flying a plane she calls ‘Harmony’ and accompanied by her flight instructor, a sixth-grader from Meadeville, Pa., believes she is the youngest girl to pilot a plane to Europe. Twelve-year-old Vicki Van Meter completed her trans-Atlantic flight Tuesday after taking her single-engine plane above the clouds to rid it of ice on the wings.” (Ann Arbor News, June 7, 1994)

postmodern postlude

To imagine Amelia not as solo flier nor as the wife in a modern marriage, but to reimagine her as the lover of her navigator Fred Noonan, becomes a symptom of the postmodern desire to write beyond the modernist ending. Noonan was a known alcoholic, like Earhart’s father, the only navigator Earhart could afford for her trip around the world, the only person ever to accompany her on a long-distance flight.

In Amelia Earhart: The Last Flight (1994), a made-for-TNT movie with Diane Keaton, they go down together and vanish, Noonan in love with Earhart, not just her flying. In Jane Mendelsohn’s novel I Was Amelia Earhart (1996), whose film rights have been sold to Fine Line, they land on an island and become lovers in a life after death, even as Earhart remains focussed on escaping their rescuers, and Noonan begins to display signs of dementia. In Alison Anderson’s Hidden Latitudes (1996) (with a sticker on the dustjacket marketing it as “A Novel of Amelia Earhart”) they become lovers while castaways on an island, perform a marriage ceremony and anticipate a child, before Noonan falls ill and is swept away by the ocean’s current, all recounted from memory by an Amelia who has lived into old age.

The postmodern rewriting de-“queers” Amelia by imagining a heterosexual romance, the one she never had, perhaps the one the contemporary woman in a dual-career marriage would like to have, or worse yet, fears she has renounced.

What if one were to land on a desert island, not preplanned and prepackaged as a tour? What if one had an affair with a male subordinate at work? What if one lived another forty years in order to experience a postmarital relationship that involved neither adultery nor divorce, but potential motherhood, for the indecisive or the infertile?

In these postmodern fictions Amelia either goes down because she’s afraid of old age or she disappears and doubles her age. She’s imagined as a survivor, or she’s imagined as immortal.

Are these the soft-porn fantasies of “sexually liberated” women?

Are these the symptoms of a feminist “backlash”?

The parallel narrative in Hidden Latitudes presents the anatomy of a contemporary marriage between Robin and Lucy who escape “modern life” on a thirty-five foot yacht only to end up stranded on an island in the Gilberts where a ghost (who may or may not be Amelia) makes herself known by stealing books and a jar of raspberry jam, leaving a coconut shell filled with potable water. Robin is a science teacher who has had an affair with a female student that almost made him cancel the trip; Lucy is being pressured to get pregnant while wondering whether her marriage is worth preserving. When she does get pregnant, she decides to keep the child, to make up for the one that “Earhart” lost after Noonan’s death.

Why does Anderson need to imagine Amelia’s story differently in order to invent her own?

Why do we need Amelia Earhart, not as girls, but as adult readers, or, especially, as first-time novelists?

What is it about the “last flight” that makes one want to rewrite it as the “last fling”? What is it about the modern heroine that makes one want to return her to the “primitive,” not as “premodern” but as the object of postmodern consumption: 30s retro, third world travelogue, desert island getaway? What is it about Noonan that makes him the ideal lover, the sensitive man who has a weakness, but is strong enough to be a provider in the wild?

On the one hand Earhart and Noonan are like a married couple, pilot and navigator; on the other hand they are like lovers, because time and place have been suspended. Once the plane is grounded, the pilot loses her job; once the pilot has saved the navigator, all he has left is his sex.

If Amelia herself has been de-“queered”, these texts nevertheless have their “queer” moments.

Mendelsohn’s Amelia is clearly in love with her plane, her desire much stronger for “Electra” than for Noonan, as she develops a homoeroticized connection to the plane in its cockpit, rather than in the (hetero)sexual union to a man who seeks his own narcissistic pleasure by getting high.

As she feels more estranged in her marriage, Lucy becomes increasingly drawn to the island, to the other woman, Amelia, who has been a mother and has lost her child, mothering Lucy so that she in turn will not make the mistake of aborting her own.

And finally, how can one not read Keaton’s Amelia as the reincarnation of Annie Hall, who by wearing men’s ties and failing to marry the hero, likewise enables “queer” identifications?

NOTES

1. Charles Lindbergh, “WE“ (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1927), 265.

2. Laurence Goldstein, The Flying Machine and Modern Literature (London, Macmillan, 1986), 98.

12. Mayor Walker quoted in Chicago Tribune, June 21, 1932, 9 (qtd. in Susan Ware, Still Missing: Amelia Earhart and the Search for Modern Feminism [New York: Norton, 1993], 19).

13. Mary S. Lovell, The Sound of Wings: The Life of Amelia Earhart (New York: St. Martin’s, 94).

14. Amelia Earhart, 20 Hrs. 40 Min. (1928; Salem, NH: Ayer Company, 1992), 11.

15. Lantern, July-August 1928 (qtd in Lovell, 111).

16. Hilton H. Railey, “Finding a Woman to Fly the Atlantic,” Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, 10 Sept 1938 (qtd. in Doris Rich, Amelia Earhart: A Biography [New York: Dell, 1989], 46-7).

17. Amelia Earhart, “Amelia Earhart Flies Atlantic; First Woman To Do It,” New York Times, 19 June 1928, 1.

18. Earhart, 20 Hrs. 40 Min., 100.

19. Earhart, “Flying the Atlantic—and selling sausages have a lot of things in common,” The American Magazine, August 1932, 17.

20. Earhart, Last Flight (1937; New York: Crown, 1988), 4-5.

21. Doris Rich, Queen Bess: Daredevil Aviator (Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993), 47.

22. Mary Loeffelholz, Experimental Lives: Women and Literature 1900-1945 (New York: Twayne, 1992), 191.

25. Anne Morrow Lindbergh, North to the Orient (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1935), 135.

26. Earhart, New York Times, 20 June 1928, 2.

27. Allen Raymond, New York Times, 20 June 1928, 2.

28. Earhart, New York Times, 19 June 1928, 2.

29. Earhart, New York Times, 20 June 1928, 2.

30. Earhart, New York Times, 21 June 1928, 1.

31. Earhart, New York Times, 22 June 1928, 1.

32. Ray Long, editorial, Cosmopolitan, November 1928, 33.

33. Earhart, “Why Are Women Afraid to Fly?” Cosmopolitan, July 1929, 71.

34. Earhart, “Why Are Women Afraid to Fly?” 138.

35. Joseph Corn, The Winged Gospel: America’s Romance with Aviation, 1900-1950 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983), 89.

36. Jane Addams, Twenty Years at Hull-House (1910; New York: Signet, 1981), 98.

37. Earhart, “Try Flying Yourself,” Cosmopolitan, November 1928, 33.

38. Earhart, New York Times, 22 June 1928, 2.

39. George Palmer Putnam, Soaring Wings: A Biography of Amelia Earhart (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1939), 41.

40. Earhart, 20 Hrs. 40 Min., 112.

41. See Karla Jay, “No Bumps, No Excrescences: Amelia Earhart’s Failed Flight into Fashions,” On Fashion, ed. Shari Benstock and Suzanne Ferriss (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1994), 76-94.

44. Terry Castle, The Apparitional Lesbian: Female Homosexuality and Modern Culture (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993), 62.

48. Elizabeth Wilson, Adorned in Dreams: Fashion and Modernity (London: Virago, 1985), 162.

49. Earhart, “Flying the Atlantic,” 72.

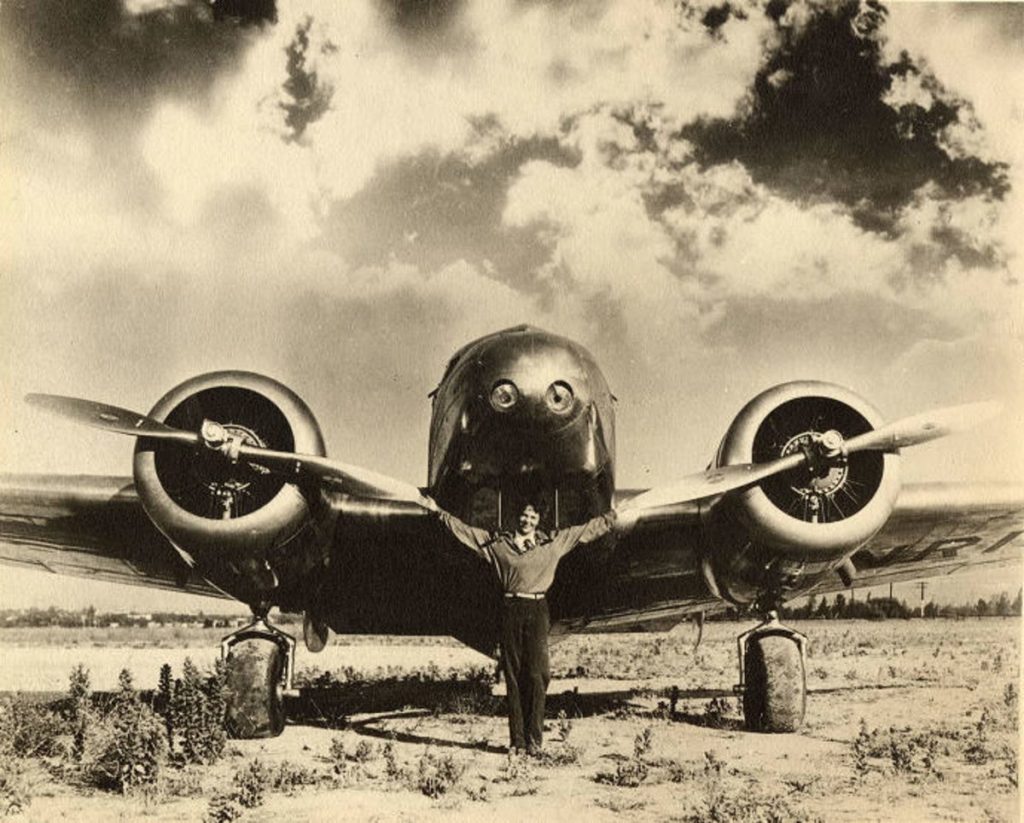

Lead image: Amelia Earhart with arms spread in front of her plane, ca. February 12, 1937. (Photo: George Palmer Putnam Collection of Amelia Earhart Papers, Courtesy of Purdue University Libraries, Karnes Archives and Special Collections.)