“What I Want to Tell: A Sequence of Rooms,” by Michael Martone, appeared in the Winter 1999 issue of MQR.

A Room

“What do you want to tell me?” a Doctor X asks me. I am in an office room, an office room very much like my own office room. It has a desk, a desk chair, and some chairs. The overhead lights, a panel in the false drop ceiling, are off. The desk lamp is on as is a torchier in the corner, its halogen humming in the silence that follows the question. What light there is sifts through a drawn blind on the window. When I moved to S four years ago, I looked up the city in the places rated guides and found it ranked first in only one category. S, with its month or so of scattered days of available sunlight, days bright enough to cast one’s shadow on the ground, is the only place to live if one wishes to avoid skin cancer. The city is famous for its cold as well. I want to tell him about when I moved to town what a colleague wrote on the title page of his book when he autographed it for me. “Welcome to S,” he told me. “With warm regards, W. P.S., You’re going to need all the warmth you can get!”

The Same Room

“What do you want to tell me?” I find the question hysterically hilarious but not so as the man who asked me, Doctor X, would know. In a word, I am depressed. I think of that word, depressed, as one of his words. My words have yet to arrive. He doesn’t know a thing about me yet as I haven’t told him a thing, and I am sitting stone still in his office thinking about what I have to tell him and how funny that is since what I have to tell him is about telling. For the last twenty years, I have made a living, more or less, telling stories, always imagining an imaginary audience prompting me to tell a story with a question like this. And I have been teaching students the last twenty years, telling them how to tell stories. And now the last year and a half I have been telling the same story about something that happened a year and a half ago, to a variety of people—investigative committees, administrators, colleagues, reporters, hearing examiners, students, friends who have called. And every time I tell the story of the thing that happened a year and a half ago, that occasion of the new telling, that version of me telling the story and the way I told it that particular time, becomes attached to the bigger story, the ongoing story, so that each time I tell the story there is more of it to tell, and when I am rehearsing the story for someone new, as I am about to do now for Doctor X, I am also not simply telling the story but paying attention to myself telling the story so that the next time I tell it I will remember to add the details of the last time I told the story, the way the room was, its light and furnishings and the person or persons there, so that those things can be incorporated into the next time I tell the story.

Still in the Same Room

What is so funny is that I have, with great authority, told my students all about where to start a story, even using Latin to give it a special patina of power. In mediasres. In the middle of things. I tell my students of this ancient technique. How to go backwards from there in order to go forward. Funny, then, that I have started here in this room, in the middle of things, to tell the story again, this time to you who are reading this story. Funny, too, that when I was in the doctor’s office and when he asked me the question, “What do you want to tell me?” I, a person who makes a living, more or less, telling stories and teaching other people how to tell stories, was silenced for the moment by the existential nature of the task. That is, that we must tell stories in some order since our words line up one after another and accumulate and are read here in a conventional sequence from the top down, from left to right, are followed step by step. Now, I am in this room because I am at the end of one rope of words. I wish at this moment I could tell the doctor what I have to tell all at once, simultaneously. Though it is true that the events that have led me here happened in a sequence so much of the sequence now seems repetitive, glossed, as if I have been polishing a table and a flat surface has taken on this depth. Rooms within rooms. I sit there. It is like a pen held to paper, this story I have to tell, the stain of ink spreading, the color deepening everywhere all at once. And I have no words, no means to make them tell. Not a line at all. A dark dark blot spreading.

Another Room (Versions)

I am not in this room. It is the end of March and dark. A party at a student’s house. A poet, D, in my department, drunk, calls a woman—not his student but a student in the department—a name and throws a drink in her face. Subsequent retellings of the events of that night would add detail, more or less, because the people there were poets and fiction writers, narrators all. It was night and dark. There was a visiting poet who later, back home in Idaho during the investigation, refused to ever tell his story. Versions vary but some say he said or didn’t say something about the woman’s breasts or D said or didn’t say something about her breasts to the visiting poet or to the woman. Which did or didn’t spark the woman to say something or not to D who was either hurt or mad by what was said or not said. He threw the drink and the liquid hit the woman, everyone agrees. But there are versions about what was said by D, the words delivered with the gesture in the air with the alcohol. I was struck later, on April Fool’s Day, when I heard a version of the events for the first time by phone along with the news that the student had filed a complaint of sexual harassment with the university, by the gesture itself. I was struck by the gesture itself, the throwing of a drink. How artificial it seemed. How like something self-consciously cribbed from a movie. The words that were or, perhaps, were not uttered, how they seemed, even then, the first time I heard them, so scripted and rehearsed. And I thought of Henry James, the great chronicler of the tragedy of the broken teacup, who wrote that stories reveal themselves through selected perception and amplification.

An Amplification

The room where I teach my workshops at the university in S has been renovated. In this old building the high ceilinged rooms have been cut in two and the floor of the room I am in now floats halfway up the old space. The tops of the old windows, then, arch frowning at our feet. Outside it is gray and cold. What light there is must struggle up, reflected from the dark ground and the stone pavement outside. We talk about the two step formula of how one gets a story started. There is the “Once upon a time” and there is the “One day.” The anecdotal “Once upon a time” seems easy for my students. They understand the chronic tensions of life, the conflicts of family, friends, lovers. They sense the asymmetry of character strengths and weaknesses, the pressures of job and gender, history and place. They know the atmospheric weight of birth and death and the specific gravity of a character’s attraction or repulsion. This they get. This they get because it seems like life, the elaboration of conflict, tension, and difference. Life is like this. What is hard is the “One day.” What is hard is the making up of the “One day,” the thing that happens that sets all of these accumulated and congested details into motion so that more happens. That is the fiction part of fiction I tell them, that is the thing that you make up. It is a coincidence, I tell them, that one day the magic mirror tells the evil queen that she is no longer the fairest in the land. Coincidences like this we accept in stories. I tell them that these coincidences are what make anecdotes stories because the “One day” allows for things to change. Our lives are a systemic melodramatic mess, busy but static. The “One day” is hard to imagine, but this is the part that must be imagined. This “One day” that changes your life. We shake our heads in sympathy with one another. How hard this will be to imagine I tell them reassuringly. How the “One day” has always been not life but the hard part of the art, the artifice of art. And then, one day, a man at a party throws a drink at a woman…

The First Room

But that is not what I want to tell Doctor X in his office when he asks me what I want to tell him. It is now the fall after the party at the end of March where D has thrown the drink and much has happened. This, the following list of events, is still happening in my head. There is the meeting in W’s office with some of the other faculty of the creative writing program where K and H and I talk about what we should do. There is the meeting in my office with the woman who was hit by the drink. And the meeting with the chairman of the department and the faculty members who make up an executive committee in the committee room with its big table which is the same room I use to teach my fiction writing classes. And this is about the time of the meeting before what I call the big meeting, where the creative writing faculty meets to decide whether we should have the big meeting. Then there is the big meeting with the open mikes and the reading of statements. And then, after that, all the small private meetings with individual students who, because of what went on with the big meeting, now have things to say about D and the program in creative writing. And this is before the investigative hearings by the faculty senate in another committee room. The meeting with the graduate students in creative writing I call the blizzard meeting because I made a reference to a late spring snowstorm that was going on as we met, the wet snow turning the tiny windows in the room white. The meeting at the Thai restaurant and at the bar before. Then, after the report came out listing D’s history of behavior but also the program’s complacency and complicit nature. The meeting in the vice president’s office where W, K, and H, the other writers in the program, denounced the whole investigation. The meeting in the office of the chairman of the investigative committee when I gave him a memo that made clear how I differed from W, K, and H about what should be done. Then the actual hearing itself where I testified in a room to a committee. The committee sat with its back to windows and I remember the sky being occluded as always, but it was summer then, June, and it might have been one of the bright blue skies worth remembering if I could remember it. D was sitting next to me on the left and the woman who brought the charges on the right. A committee member asks me, “Given all that was going on in your program why didn’t you do something?” And I say, “This is what I am doing. I am doing this now.” And I could start with that or with the summer writers’ conference two weeks later where I am on the staff with D who hears, that week, the results of the hearing and leaves early and where I hear from the new chair of the English Department that the other teachers of creative writing, W, K, and H, now are angry at me. But I didn’t start in any of these places. I started at the meeting that happens later that summer where I sit for five hours and listen to W, K, and H angrily tell their stories about me and, afterwards, in an office very much like mine, I weep for two hours more, not only because what they have said about me has hurt but because I know that the things they have said have been designed to hurt, and I realize that I need help. I need a way to stop telling the story of these stories. The meetings in meetings. I need, I understand, a story that would no longer nest in a nest of other stories.

An Amplification

Crying is funny. I am holding on to the arms of the office chair I am in, howling. Every time I come up for air, I am conscious of the secretaries outside this office at their desks in the outer office. Surely they can hear these noises, these sounds I am making. The gagging. The sputtering. The hiccups of breath. The empty whoops. The plosive sighs. They must hear this on the other side of the glass wall and hollow cored door. Filtered I could sound like a Stooge whose own comic sound effects accompanies his beating. Two friends are holding me down, it seems, in the chair. I let them touch me. I want them to touch me. And they are making sounds too, a kind of burbling murmur that comforts me when I hear it and initiates a whole new burst of wailing in me, hearing it, out of gratitude. I have no words but this slurry of speech. I am way beyond words in this place. I am letting go. Perhaps that is why I am clinging so hard to the arms of this office chair, why my friends have collapsed across my knees, wrapped their arms around my shoulders. It is as if I would levitate on all the unsounded breath I am gulping. I believe I am communicating that, for a while here in this office, I don’t want to talk anymore. I have come here after five hours in a room in the Philosophy Department. At this moment, I am remembering just one sliver of what went on. I remember H instructing me on my attitude, my manner, the way I choose my words. He says I have, upon occasion, been sarcastic, then defines the word for me, its roots, as the ripping of flesh. When I was a student, a teacher told me that humans use language to convey only one message: “Do you like me? Do you like me? Like me!” I remember laughing when I heard this for the first time, a kind of witty distillation of experience teachers deliver in a classroom and which passes and is passed along as a truth.

A Room in the Philosophy Department

In August, the chair of the English Department arranges a meeting with a professional mediator. It is held on the top floor of my building where one wall is all windows looking out over the hazy sky. Off in the distance I can see what everyone says, quite proudly, is the most polluted lake in the Western Hemisphere. I didn’t want to meet again. I sensed what was coming. But the chair assures me the mediator is a pro and will be fair. I walk last into the room in the Philosophy Department and notice the table where W, K, and H sit is sown with mini Hershey bars the mediator is encouraging us to eat. As I recount this detail, Doctor X snorts. And I tell him the mediator says that chocolate will relax us. I continue my story about the meeting in a room of the Philosophy Department. I realize the mediator with her big felt pens and clipboards and xeroxed ground rules about “no piling on” is not anticipating the meeting for which I know we have met. She is attempting to manage a group of angry, professionally verbal people with chocolate and chalk. W’s most recent book about the trauma of his experience in Vietnam will be a National Book Award finalist. K’s new memoir of her childhood will soon be on the best-seller list. Between us I count a couple dozen books and a half century of classroom teaching. The mediator, according to her résumé, has authored articles entitled “Teambuilding in a Technical Environment” and “Using Psychology to Reward Teamwork.” In her report written after the meeting, she writes that the bad feelings will dissipate. Like the weather, I think. In W’s boyhood memoir, the one he autographed for me with warm regards, there is a scene where his evil stepfather sadistically makes him clean out every bit of mustard from an empty jar W threw away. The stepfather twists the jar into W’s eye. Is it empty? I call this meeting, the meeting in August in a room in the Philosophy Department, the Mustard Meeting. We are going to get every bit of mustard. We play along with the mediator a while. I look out the window. The lake. The clouds. K, impatient, says to W, ignoring the mediator who never speaks again, “Do you want me to start or do you want to?” He wants to.

The Waiting Room

This is nothing. I know this is nothing compared to what has happened to other people, what is happening to people now, what is happening to the people here, say, in Doctor X’s waiting room. It is nothing in comparison. It wasn’t bodily trauma in any way. I am not physically ill. I am not dying. Nor have I struck anyone. I do not feel like striking anyone. This is about something that happened at work, I keep telling myself, something that is now way out of proportion. What happened finally, I think, was I couldn’t fix things when I thought I could. I thought that things could be fixed. Or I thought things needed fixing. Something. It occurs to me, in the waiting room, that since last March I have been sitting in my office listening to students and colleagues tell me stories about the consequences of D’s actions and being helpless really. How do I feel in the waiting room? Embarrassed. Embarrassed that I am so stunned by this nothing. Embarrassed that I have hired a professional listener to listen to my tale. And I am taken by the luxuriousness of this, of hiring an audience, this utter indulgence. I am depressed, depressed with a small D. To me, the depression is a kind of small black dot, a dot no bigger than the period at the end of the sentence, at once an insubstantial speck of ink while at the same time a collapsed world with the specific gravity of a black hole. I am taken by this paradox. I am insisting too much on this nothing. What has happened is, in my professional opinion, boring, yet I am deeply fascinated with the intricacies of the events. The storyteller in me keeps telling me there is no story here really. But I can’t stop wanting to make it a story. I can’t stop telling it. This is nothing but it has become everything. By calling it nothing I can’t rid myself of it. And I am quite conscious of the inconsequence of all this to others. They see it as the nothing it is. They suggest, politely, at the end of another rendition that I talk to someone. And here I am. Here I am ready to tell this story again.

A Room in a Basement of a Church

In the middle of things, a friend takes me to an open AA meeting. He suggests that, though I don’t drink, alcohol in this crisis has profoundly changed my life. D was drunk when he threw the drink, and he did throw a drink, and has offered that—that he was drunk—as a mitigating circumstance and has indicated that he has entered the program. He is sober now, he says. A changed man. The room in the basement of the church feels, oddly, like my classroom where stories are told, tables and chairs, but it is not like my classroom. The framing of the storytelling is different. And my friend who is a literary scholar tips me as to the aesthetic differences to come. He tells his story to us without the literary flourish I know he knows. He has told me that the notions of creativity and originality are different in this room. The stories are supposed to be repetitious and predictable. And they are. They are relentless in this relentless style, their stylelessness. That’s the point. The one day here does not lead to a rising action, climax, and denouement but to the next one day and the next.

In Camera

After another day of meetings, I sit in the living room, the answering machine on, screening calls. My wife and I watch television and, during the commercials, I rehearse for her the scrolling events at school. The phone rings, and we both start. We hear an angry voice laying down a track on the tape. New threats and curses. An aggressive gloss of the very version of events I have just related to my wife. All night, every night, for months voices emanating from the machine. “Talk to me, you sorry son of a bitch” or “Call me, I’ve got something to say to you.” The little box of the TV we watch seems to have only one story to tell. Scandal and corruption everywhere it seems. The detective stories, all the investigations, only reveal ambiguous evidence. Locally, the story I am involved in disappears in the local news as another sexual harassment investigation blooms at the nearby airbase. Men and women fighter pilots fighting. My wife and I, everyone I know, longs, I think, for an actual dogfight. The gray jets screaming and looping in the gray skies above the city of S. Instead there are the usual waves of statements and denials, charges and counter charges issued for the press with or without attribution. The whole catastrophe. Behind the stock footage of the F-16s skidding down the runway in the late season snowstorm, I imagine the G-suited pilots in the cockpit of their offices, the warrens of their bureaus, the meetings and workshops, the sessions with consultants. It is the season of debriefing. And I imagine that cast of characters in their own living rooms watching this broadcast, the one I am watching, listening to this endless spool unraveling, taken from the wreckage, the black box of this crash that keeps crashing.

Another Amplification

For years I have been routinely sketching for my students the theory of realistic fiction, the one that ties it to the rise of the middle class and the invention of privacy and leisure. There is time now, I suggest, to read books and there are places now where one can go to read them. And the content of domestic fiction? This reiteration: Intimates keep secrets from one another. The drama is in the discovery of those secrets and the discovery of the depth of those secrets. Adultery, a favorite theme. The metaphoric exhaustion of an upstairs and down. The closets that are rooms within rooms. Could Freud have even evolved his theories without the elaboration of all the specialized rooms within the detached house? The bathroom! The bedroom! The innovation of the hallway was profound, I say. No more walking through rooms to get to other rooms. Doors can be closed in order that secret things go on behind them. I see my students roll their eyes. This is all theory, I say, laughing, this storytelling that takes place within walls that turn transparent, that is about the renovation of the chambered spaces of the house and the heart and the head.

In the Room

I want to tell him everything but there isn’t enough time. That’s not it exactly. There isn’t enough space either. I can only provide a map of this disaster and the scale will always be distorted, will not correspond point to point. You can’t feel what I feel. I tell him this. And I tell him this: How hard this is to tell. And I muse for a moment about such a map, a map on the scale of 1:1, a map that when we unfold it would map everything exactly. The map would settle on those chairs, the desk, on us exactly, a new skin, would correspond exactly molecule to molecule. You would feel what I feel. I have run out of words. I look around for another handy metaphor, another physical tool to pry open all the abstractions. Any port in the storm. It is the place, I suggest, that has made me so sad. This particular combination of physical detail. Maybe it’s in the water, the air. It is always so cold and so dark. We both look at the window, and Doctor X draws open the blinds dramatically. The lumens in the room increase infinitesimally. We regard the familiar gray sky, the light my wife jokes about each morning. The famous light, she says, painters come here from the whole world over to capture.

A Final Amplification

I edited a magazine once called Poet&Critic, and, as part of a promotion campaign, I ran a contest for a poster design to feature the words POET and CRITIC. I received fifty entries, and all but one characterized POET in a display font that was flowery and fluid, italic at the very least, but always cast to look improvisational, spontaneous, creative. The CRITIC, on the other hand, was figured as severe, in serifed types or bold block letters, regimented and defined. Only one designer reversed this take—the POET permanent and the CRITIC scribbled in by hand. And that was right. That was it exactly. All the stories I have read, all the books and magazines and typescripts—these were printed, set in type. It is my scrawl of analysis, my random thoughts, the critic in the margin and between the lines, the editor that ferrets around by hand amending commentary. It is so difficult to see the obvious. I watch Doctor X scribble on a pad of yellow legal paper as I talk. I tell him about a story I read once. The story was about Superman, the comic book hero, but it was a pop treatment. The author’s trick was to take the conventions of the form and the character to logical conclusions. When Superman, in this story, uses his x-ray vision, I tell Dr. X, all he sees is lead. The x-ray keeps going, see, through everything until it can’t go through anything more, until it runs into some lead. And in this story, I say, Superman’s speech balloons and his bubbles of thoughts are invulnerable like the rest of him. He says something or he thinks something and the words appear for a second above his head and then they drift down, coating him in verbiage, a kind of sticky paste, layer after layer, impervious to detergent or thinner. Our hero encased in a cocoon of words, the light filtered by the thatch of entwined letters.

In the Waiting Room

“You can go,” Doctor X says. I am in his office and I take his “you can go” both ways. That is, I can go now and leave this room which is, I realize at this instant, a kind of waiting room now, outside, as it is, of the next room I must enter. Or I can go, leave this place, this S, altogether. There was a moment in the Mustard Meeting, in the room in the Philosophy Department, a moment when I knew I would go. With the silent mediator opening square after square of chocolate, enthralled by the stories being constructed by W, K, and H. In the middle of this, I was struck by the thought that all was lost, that I was lost. I was an M. I was merely a character now in this room, in this place, written out in the meantime, in the corroborating narratives of W, K, and H, reiterated in the meetings they had together in the run-up to this meeting with me. An M. An M who had been written up and written off. I wasn’t in that room anymore. So I could go. And I went.

The Copy Room

I am in the copy room, copying my vita, an academic résumé. The copy room is windowless, air forced in through vents near the ceiling. The wall of shelves is stacked with reams of white paper, letter and business. The lights hum and the copier stutters through its cycle. All around are the fossil remains of extinct business machines, heaps of the obsolete technologies of duplication—thermagraph, ditto, mimeo—their cords coiled. The machines are clad in those exhausted colors—putty, gunmetal, drab. With each swipe it makes, the green light of the Xerox machine leaks a little from beneath the lid. For the purposes of furthering my employment opportunities elsewhere, I have reduced my life to a page of copy. I am making fifty copies of the copy. The vita’s form is boilerplate. There are bullet heads for EDUCATION, AWARDS, PUBLICATIONS, TEACHING, SERVICE, in bold all caps. H comes into the copy room, queuing up behind me. We exchange pleasantries. “Be done in a jif.” We have all been pleasant this fall after we have CLEARED THE AIR in the August meeting, the one I call the Mustard Meeting. That’s how W, K, and H characterize what happened then and there: THE AIR WAS CLEARED. WE CLEARED THE AIR. On my vita, there is the bullet labeled EXPERIENCE, and I have advertised there the position I still hold, Director of Creative Writing. The meeting in August, the one I call the Mustard Meeting, was held because W, K, and H had LOST CONFIDENCE in me as Director. Now a few weeks later I am still Director. “Be the Director,” I was told at the end of the Mustard Meeting. You know, Doctor X says to me in his office, this hasn’t been about you as Director. This hasn’t been about CLEARING THE AIR. This hasn’t been about LOSS OF CONFIDENCE. The copy machine performs its little rumba of reproduction, counting down to nought.

The Cloud Room

Before we go out to the car to go for good, we walk through the empty house in S, my wife and I and our two boys. We say goodbye to all the empty rooms, starting in the basement where Sam had set some handprints on a jacking pad we’d poured when we moved in. I carry the little one, Nick, the two year old, and borrow the chant from one of his bedtime story books. I have learned, in telling my stories to Doctor X, in listening to myself tell my stories to Doctor X, the power of litany to both cudgel and comfort. At this moment, I am all for the possibility of comfort, the soothing murmur of the lullaby, of language laying to rest. Say goodbye, I say. Goodbye kitchen. Goodbye dining room, goodbye. Goodbye living room. Goodbye stairs. Goodbye your room and goodbye Sam’s room. Goodbye our room. Goodbye bathroom. Goodbye Mom’s office painted school bus yellow. We climb into the finished attic where some sorry soul poked a few skylights through the roof to get what sun there was, my office, where I wrote, three storeys up inside a blue house. The cloud room, Sam called it when he first saw it. Dad is in the cloud room. Say, goodbye cloud room, goodbye.

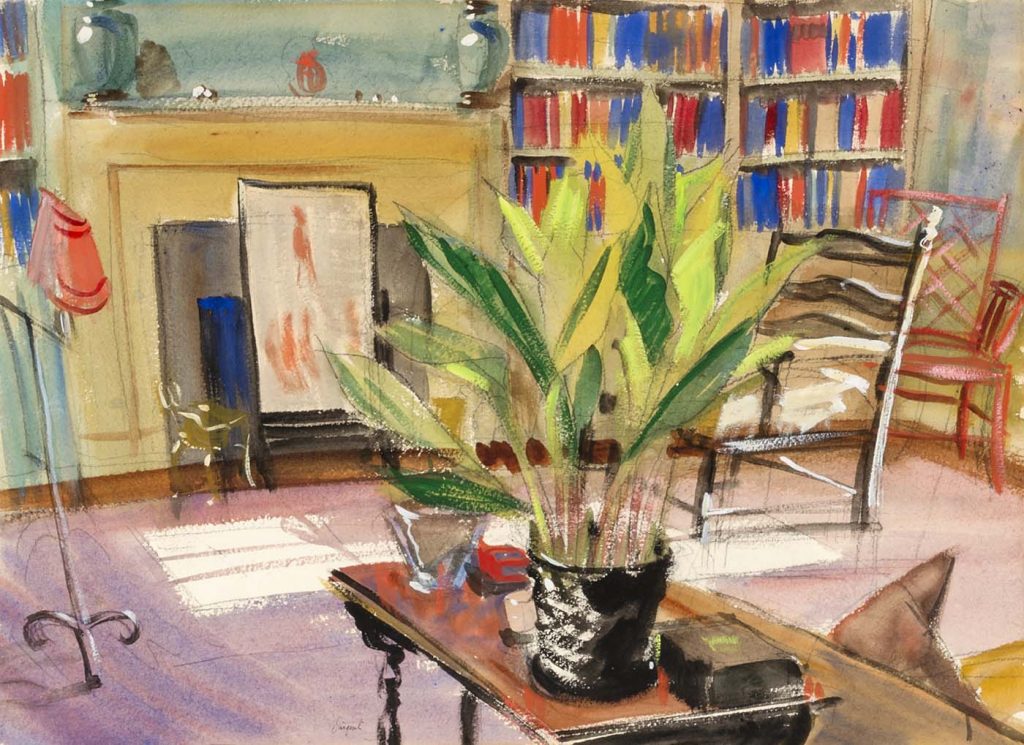

Image: Sargent, Richard. “Untitled (Room Interior).” N.d. Watercolor and pencil on paper. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.