“Primal Postcards: Madeline as a Secret Space of Ludwig Bemelmans’s Childhood,” by Mary Galbraith, appeared in the Summer 2000 issue of MQR.

Picture books offer serious artists a space to return to and depict the dramas of their own childhoods. However, picture-book editorial mandates for a light tone and for content suitable for young children serve as an external censor that drives intense feelings—grief, terror, unbearable pain, and even ecstasy—underground. In addition, picture-book creators’ own defenses customarily keep them from fully realizing what they are depicting in their work. The expectations and defenses of readers similarly keep disturbing content at a safe distance or out of awareness. Paradoxically, then, under the protective cover of a children’s storybook, primal scenes that would otherwise stay buried can surface without being consciously recognized.

From encountering several classic picture books that fit this pattern,[1] I hypothesize that a necessary ingredient to make a picture book a classic—that is, a book of great and enduring literary value and appeal that meets the conventional criteria of a picture book for a manifestly light tone and happy ending—is that the book be motivated throughout by a creator’s restaging of early trauma (primarily through allegorical narrative and line drawing). One or more pictures stand out as the book’s primal raison d’etre; that is, there is at least one picture which activates a “flashbulb memory” from the creator’s childhood and which the story explains in an ambiguous way. The manifest storybook explanation for this primal scene is benign and reassuring while the latent and historical interpretation is traumatic and unbearable. Thus, the classic picture book can be seen as a secret space of childhood whose deepest significance is hidden in plain sight.

A masterful and amply supported example of such an auteur picture book is Ludwig Bemelmans’s Madeline, originally published in 1939. This storybook’s forty-four pages of seemingly light entertainment feature one child’s story of primal loss, death, war, and a bittersweet survival, and range in scope from intensely private scenes to evocations of world history, all against a backdrop of joyful immersion in color and form. In order to convey a sense of these riches, I will first sketch events from Ludwig Bemelmans’s “Swan Country” period from birth to six, and his Lausbub period from six to sixteen.

Ludwig Bemelmans was born in 1898 in Austria during the last days of Empire, the child of a failed marriage between an eccentric Belgian artist and a German brewer’s daughter. The boy spent his earliest years on the grounds of his father’s Austrian hotel in Gmunden, cared for by a Frenchwoman whom he called Gazelle (his pronunciation of Mademoiselle). Reliving his earliest memories in an essay called “Swan Country,” Bemelmans recalled that “I was her little blue fish, her little treasure, her small green duckling, her dear sweet cabbage, her amour” (Bemelmans 1985, 7). Gazelle may well have suckled Ludwig, since putting a child out to nurse was the custom among well-off Germans at that period. According to Doris Drucker, who was a young child in Cologne and Mainz during the prewar and wartime years between 1910 and 1918,

A wet nurse was usually a village girl who had gotten herself “into trouble.” As soon as her baby was born, it was given away to an “angel maker” (a woman who starved to death the babies in her care), and the young mother was hired out as a wet nurse. (77)

In any case, Gazelle nurtured the boy on “long hours [. . .] with postal cards of Paris, the Album of Paris, the children’s stories of France, the songs written for French children” (Bemelmans 1985, 10), even as he imbibed through her the rhythms, colors, and weather of Gmunden. In the picture accompanying, a portrait of himself and Gazelle drawn from memory, note how Ludwig’s head overlaps her body in the shelter of a small gazebo covered with vines—the vines that will reappear as an organizing motif in Madeline.

Bemelmans’s father’s sexual liaisons apparently included not only Ludwig’s mother and Gazelle, but Ludwig’s maternal grandmother. When Ludwig was six-years-old, Lampert ran off with yet another woman, leaving both Ludwig and Gazelle, who was pregnant with Lampert’s child. In despair, Gazelle committed suicide by drinking sulfured water. If she indeed had given birth out of wedlock before becoming Ludwig’s nurse, with the results as described by Drucker, the prospect of repeating this scenario may well have been unbearable. Without making clear what story he was told about these events as a child, Bemelmans later summarized his child hood feelings thus:

And then one autumn the leaves in the park were not raked, the swan stood there forlorn and it was all over—all had come to an end. Papa was gone and so was my governess, and I wished so much that he had run away with Mama and left me Gazelle. (Bemelmans 1985, 10)

In the aftermath of this devastation, Ludwig’s mother—a virtual stranger to him and also pregnant—came and took him to live with her parents in Regensburg, Germany. At that time, he did not speak German (Miller and Field, 264-5).

In the beginning Mama tried to replace Gazelle: mostly in tears, she dressed and undressed me. [. . .] [S]he would tell me stories about her own childhood—of how alone she had been as a little girl and how she was shipped off to a convent school. . . . She was much happier there than at home, for her parents had never had any time for her. This made me sad. She cried, and I cried. She lifted me up; I looked at her closely, and a dreadful fear came over me. I saw how beautiful she was, and I thought how terrible it would be if ever she got old and ugly. (Bemelmans 1985, 10-11)

After this beginning, his mother became hardened in her care of Ludwig and “was determined to erase all traces of the past from me.” Thus began Bemelmans’s Lausbub years, in which German relatives tried to make a German out of him: “The golden curls came off my head, I was shorn and put into new clothes, high-laced shoes with hobnails.” The effect on the boy was to make him intentionally defiant. “I said to myself they can kill me, but I won’t give in. I will not change, never never never” (quoted in Marciano 6). When he was a young adolescent, the lyceums he was sent to tried to cow him into submission, but he persisted in behaving with Gallic fatalistic flair, and he was sent home from them all in disgrace.

Again he was sent away, this time for a stint in the family hotel business in Tyrol, and again he skirted Teutonic authority. Then in 1914 he did something more serious. In an interview with the New York Times in 1941, Bemelmans described this serious offense: while working in one of his uncle’s hotels as a busboy, a “vicious” headwaiter threatened him with a whip. “I told him that if he hit me I would shoot him. He hit me and I shot him in the abdomen. For some time it seemed he would die. He didn’t. But the police advised my family that I must be sent either to a reform school or to America” (Van Gellens 2). Whether or not this “abdominal wound” story is factually correct—Bemelmans treated the distinction between fact and fiction as something to play with—something else stands out about the time of his exile to America: it came four months after the beginning of all-out European war. Because of his “serious offense,” Bemelmans sailed to America in December 1914, escaping service as a “potato-head” in the Central Army and death in the trenches of World War I. His escape recalls the widespread use of self-wounding, and the less common but well-known practice later in the war of shooting superiors as a means to escape the inexorable march to the front. Bemelmans was not opposed to military service per se—he later enlisted in the Allied Army and served in a mental hospital in New York—but to the brutal and oppressive militarism he associated with Germany.

Madeline’s story centers on four primal breaks in the life of Ludwig Bemelmans: first, the suicide of Gazelle when he was six; second, his immediately subsequent introduction into German discipline; third, his “disgrace” and evacuation to America in 1914 at the beginning of World War I when he was sixteen; and fourth, the wholesale wartime slaughter of his European age mates (his only brother also died an untimely death).

In addition to the disguised presentation of these events, Bemelmans portrays his own perceived relation to and response to these traumas—crying out for help from his bed, resisting regimentation through defiant behavior, escaping from mobilization in the Central Army by means of a “self-inflicted” abdominal wound, and grieving the loss of his peers.

Specific uncolored pictures in the book capture Bemelmans’s traumatic experiences as fused and condensed tableaux: the last picture in the book combines a flashbulb memory of his last sight of his beloved Gazelle (“there wasn’t any more”) with a complex portrayal of Europe’s response to its traumatized youth in World War I; the picture of an elevated but isolated Madeline standing on her bed exhibiting her abdominal scar memorializes both the triumph and the trauma of his escape from the Lausbub life at age sixteen; and the repeated pictures of two rows of “soldiers” divided by a “trench,” culminating in the picture of the eleven remaining children wailing in their beds too late to escape their fate, register regimented school life as well as the slaughter of millions in World War I.

In addition to objectified figures representing himself as child and artist—Madeline and a mysterious unmentioned figure in a fez who haunts the pictures—the background atmospherics of tone, color, weather, and landscape evoke the sensory and emotional preverbal experience of Ludwig Bemelmans with Gazelle in his “Swan Country” period, when she was for him a place as well as a person. Among these atmospheric elements are the postcard landmarks of Paris which Gazelle used to pore over with him in the wintertime, and the sensuality and emotional significance of the light and weather—rain (which Gazelle referred to as the tears of le bon Dieu), snow, and darkness predominate, and the sun is a glorious face shining upon Madeline after her return to consciousness in the hospital. In the color pictures early in the book, even the air is a palpable and womb-like presence, saturated with the personal relationship to form and color Bemelmans describes elsewhere from his earliest memories. Significantly, the early pages of his “Swan Country” memoirs contain no “I,” since the “I” is still completely immersed in its experience. Similarly, the landscape and weather in the early pages of Madeline evoke an immersed time before the “I” is objectified.

The placement of the uncolored pictures also carries meaning. After the narrative switches focus from Madeline to the other eleven girls, there are no more color pictures—enacting both the change in Bemelmans’s life after Gazelle’s death when he was six, and the situation of his age mates as they approached the age of being mobilized. The pictorial narrative here is carried by Bemelmans’s expressive cartoons only. Most notably momentous are the line drawings of Miss Clavel as she runs fast and faster in fear of a disaster—her figure, always missile-like, assumes the energy and drive of a launched artillery shell that penetrates the room where the doomed eleven are crying out.

Madeline’s story captures Bemelmans’s survival strategy for coping with abandonment in his early childhood and for responding to the threat to his life from authoritarian adults from age six to sixteen. When Madeline emerges as an individual separate from her eleven compatriots, she exhibits the defiant attitude by which Bemelmans survived after he moved to Germany with his mother. In the narrative of the book, a scenario opening “In the middle of one night” and then “In the middle of the night” is played out twice, first for Madeline and then for the other eleven: being trapped in a room with disaster looming and without access to a comforting or rescuing body, a child cries out for help. Madeline’s cry works, at least well enough to save her life: she gets cradled, carried away, and saved, but now she is separated not only from her family but from her peers. Everyone else’s cry is summarily dismissed; the door closes on them and “there isn’t any more.”

The attachment dynamics of Madeline, and of Bemelmans’s primal scenario, are centered on access through doorways. Miss Clavel is seen ambiguously in a protective or blocking position over and over in doorways throughout the picture book. When Madeline reaches the hospital (an event resonating with Bemelmans reaching the United States), Miss Clavel (a fusion of the loving but finally abandoning Gazelle, European nun-teachers, and the madonna of wartime death) no longer controls the doorway, but both her presence and her loss cut both ways in Bemelmans’s life:

In the middle of the night, I often wake up—and stare at the open doors through which I cannot walk and at the closed ones that I can’t open—and the children’s books that keep me from blowing out my brains are created in this hour [. . .] . (Bemelmans letter, quoted in Collins 130)

Seen through this lens, the child Madeline crying in bed in the first “middle of the night” and the eleven other children in the bed in the second “middle of the night” all express premonitions of or reactions to the unbearable loss of Miss Clavel and to the unbearable horrors of war. Finally, they express the “traumatic awakening” (Caruth 91) that is Bemelmans’s personal legacy, and his survival through an artistic expression that honors and is made possible by his earliest experiences of love and vibrant beauty:

Like the pages of a children’s book, the days were turned and looked at, and the most important objects in this book were the sun, the moon and the stars; people, flowers and trees. Large trees, whose leaves throbbed with color and which reached up to the sky—black tree trunks, sometimes brownish-black and shining in the rain, young in spring, and yellow in the autumn, when each leaf in the light of afternoon was like a lamp lit up. [. . .] The sky is blue, the gardener’s apron is greener than spinach. The eyes of Gazelle are large and brown and kind. (“Swan Country,” Bemelmans 1985, 3-4)

1. A partial list: Millions of Cats, The Story of Babar, And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street, Goodnight Moon, Moon Man, and Where the WildThings Are. Other picture books clearly motivated throughout by childhood trauma experiences are The Lonely Doll and CuriousGeorge, but I see these as being in such thrall to a punishing parental position that their emancipatory force, and thus their artistic stature, is compromised, though both books exercise a continuing fascination. On the other hand, The Snowman is a masterpiece, but too mournful even in its manifest content to qualify for the limited genre I’m considering here.

I. Works by Bemelmans (for a complete list, see Eastman or Marciano, below):

Madeline. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1939.

Tell Them It Was Wonderful. Ed. Madeleine Bemelmans. New York: Viking, 1985.

II. On Ludwig Bemelmans’s life and work:

Collins, Amy Fine. “Madeline’s Papa.” Vanity Fair 455, July 1998: 116-30.

Drucker, Doris. “Invent Radium or I’ll Pull Your Hair.” The Atlantic Monthly, August 1998: 73-91.

Eastman, Jacqueline. Ludwig Bemelmans. New York: Twayne, 1996.

Marciano, John Bemelmans. The Life and Art of Madeline’s Creator. New York: Viking, 1999.

Van Gelder, Robert. “An Interview with Ludwig Bemelmans.” New York TimesBook Review, 26 January 1941, 2+.

III. On creativity and primal experience:

Barrett, William. “Writers and Madness.” Literature and Psychoanalysis. Eds. Edith Kurzweil and William Phillips. New York: Columbia University Press, 1983.

Freud, Sigmund. Writings on Art and Literature. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1997.

Miller, Alice. Thou Shalt Not Be Aware. Trans. Hildegarde and Hunter Hannum. New York: Meridian, 1984.

_____ Pictures of a Childhood. Trans. Hildegard Hannum. New York: Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, 1986.

_____ The Untouched Key: Tracing Childhood Trauma in Creativity and Destructiveness. Trans. Hildegarde and Hunter Hannum. New York: Doubleday, 1990.

IV. On picture books and primal experience:

Galbraith, Mary. “‘Goodnight Nobody’ Revisited: Using an Attachment Perspective to Study Picture Books about Bedtime.” Children’s LiteratureAssociation Quarterly 23, No. 4 (1999): 172-80.

_____ “Agony in the Kindergarten: Indelible German Images in American Picture Books.” In Jean Webb, ed., Text, Culture and National Identity in Children’sLiterature. Helsinki: NORDINFO Publication 44, 2000.

_____ “What Must I Give Up in Order to Grow Up? World War I and Childhood Survival Schemas in Transatlantic Picture Books.” The Lion & the Unicorn, forthcoming special issue on “Children and War.”

Lanes, Selma. The Art of Maurice Sendak. New York: Abrams, 1980.

Lobel, Anita. No Pretty Pictures: A Child of War. New York: Greenwillow, 1998.

Nathan, Jean. “The Secret Life of the Lonely Doll.” Tin House 1, No. 2 (Fall 1999): 32-52.

Ungerer, Tomi. Tomi: A Childhood under the Nazis. Niwot, Colorado: TomiCo (Roberts Rinehart), 1998.

V. On early childhood trauma and the production of visual narrative:

Caruth, Cathy. Unclaimed Experience: Trauma, Narrative, and History. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

Masson, Jeffrey, ed. The Complete Letters of Sigmund Freud to Wilhelm Fliess, 1887-1904. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1985.

Share, Lynda. When Someone Speaks, It Gets Lighter: Dreams and theReconstruction of Infant Trauma. Hillsdale, NJ: Analytic Press, 1994.

Terr, Lenore. Too Scared to Cry: Psychic Trauma in Childhood. New York: Basic Books, 1990.

Wright, Kenneth. Vision and Separation: Between Mother and Baby. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson, 1991.

VI. Picture books cited (original editions):

Bemelmans, Ludwig. Madeline. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1939.

Briggs, Raymond. The Snowman. New York: Random House, 1978.

de Brunhoff, Jean. Histoire de Babar, le petit elephant. Paris: Editions du Jardin des Modes, 1931.

Gag, Wanda. Millions of Cats. New York: Coward-McCann, 1928.

Rey, Hans Augusto. Curious George. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1941.

Sendak, Maurice. Where the Wild Things Are. New York: Harper & Row, 1963.

Seuss, Dr. [Theodor Geisel]. And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street. New York: Vanguard, 1937.

Ungerer, Tomi. Moon Man. New York: Harper & Row, 1967.

Wright, Dare. The Lonely Doll. New York: Doubleday, 1957.

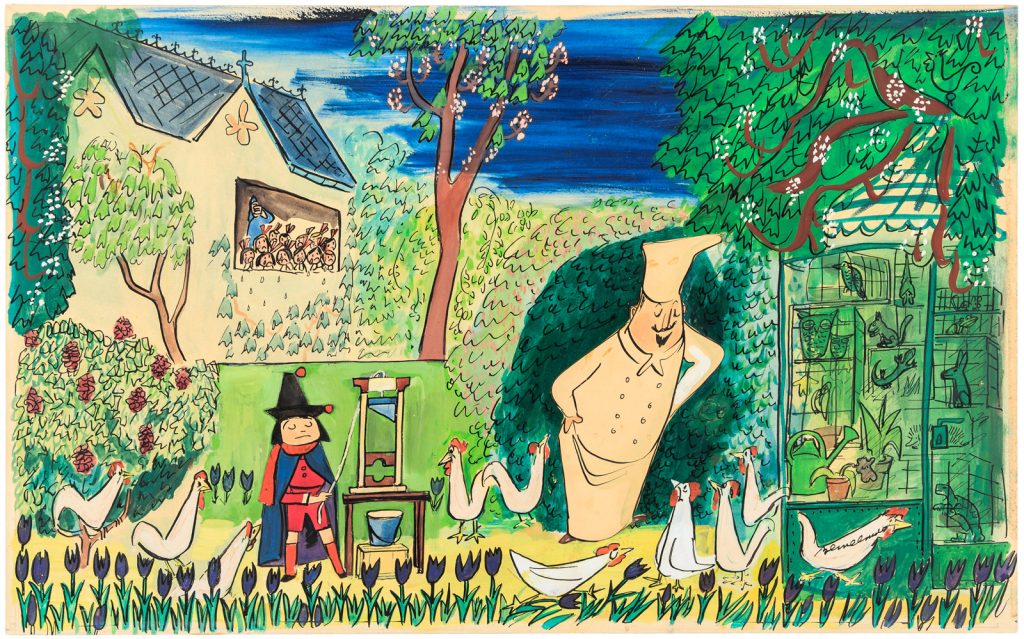

Lead image: Bemelmans, Ludwig. “He Built Himself A Guillotine,” an illustration from Madeline and the Bad Hat. 1956. Ink and watercolor wash on Whatman Drawing Board.