“Rhyming Action,” a selection from Charles Baxter’s collection of essays on fiction, Burning Down the House, appeared in the Fall 1996 issue of MQR.

For the last three hundred years or so, prose writers have, from time to time, glanced over in the direction of the poets for some guidance in certain matters of life and writing. Contemplating the lives of poets, however, is a sobering activity. It often seems as if the poets have extracted pity and terror from their work so that they could have a closer first-hand experience of these emotions in their own lives. A poet’s life is rarely one that you would wish upon your children. It’s not so much that poets are unable to meet various payrolls; it’s more often the case that they’ve never heard of a payroll. Many of them are pleased to think that the word “salary” is yet another example of esoteric jargon.

I myself am an ex-poet. My friends the poets like me better now that I no longer write poetry. It always got in the way of our friendships, my being a poet, and writing poems. The one thing that can get a poet irritated and upset is the thought of another poet’s poems. Now that I do not write poetry, I am better able to watch the spontaneous combustion of poets at a distance. The poets even invite our contemplation of their stormy lives, and perhaps this accounts for their recent production of memoirs. If you didn’t read about this stuff in a book, you wouldn’t believe it.

Prose writers, however, are no better. Their souls are usually heavy and managerial. Prose writers of fiction are by nature a sullen bunch. The strain of inventing one plausible event after another in a coherent chain of narrative tends to show in their faces. As Nietzsche says about Christians, you can tell from their faces that they don’t enjoy doing what they do. Fiction writers cluster in the unlit corners of the room, silently observing everybody, including the poets, who are usually having a fine time in the center spotlight, making a spectacle of themselves as they eat the popcorn and drink the beer and gossip about other poets. Usually it’s the poets who leave the mess just as it was, the empty bottles and the stains on the carpet and the scrawled phrases they have written down on the backs of pizza delivery boxes—phrases to be used for future poems, no doubt, and it’s the prose writers who in the morning usually have to clean all of this up. Poets think that a household mess is picturesque—for them it’s the contemporary equivalent of a field of daffodils. The poets start the party and dance the longest, but they don’t know how to plug in the audio system, and they have to wait for the prose writers to show them where the on/off switch is. In general, poets do not know where the on/off switch is, anywhere in life. They are usually off unless they are forcibly turned on, and they stay on until they are taken to the emergency room, where they are medicated and turned off again.

Prose writers, by contrast, are unreliable friends: they are always studying you to see if there’s anything in your personality or appearance that they can steal for their next narrative. They notice everything about you, and sooner or later they start to editorialize on you, like a color commentator at a sports event. You have a much better chance at friendship with a poet, unless you are a poet yourself. In your bad moments, a poet is always likely to sympathize with your misery and in your good moments to imagine you as a companion for a night on the town. Most poets don’t study character enough to be able to steal it; they have enough trouble understanding what character is.

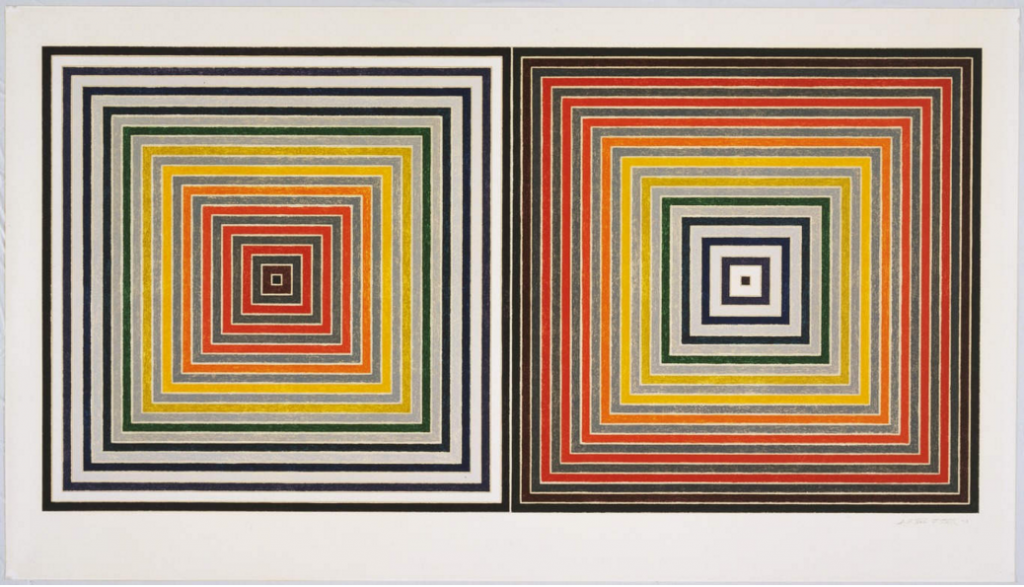

Image: Stella, Frank. “Double Gray Scramble.” 1973. Screenprint. MoMA, New York.