Two students of mine recently asked me how to go about writing the impossible. They each had a narrative that was at once their own and also not: one was trying to write through his experience of being present during a national tragedy and another was trying to write about her illness, which was advancing at an exponential rate. I told them each that there were two possibilities: either they were resistant to taking on the responsibilities inherent in the act of narrating and they needed to face and embrace them—even if that meant getting it wrong—or their stories were unlanguagable, in which case they would have to find a new framework for giving the narrative voice. What am I trying to say? they each asked me and I told them that wasn’t the right question.

*

In his one-paragraph short story “On Exactitude in Science,” Jorge Luis Borges articulates the plight of a town that obsessively charts their land’s territory until the map designed to aid in navigation becomes transposed perfectly over the land the map hoped to trace “coincid[ing] point for point.” This piece offers a beautiful introduction to the relationship between literature and the world in which we inhabit, underscoring the notion that all writing—creative, critical, or something in-between—is a practice in decision making. What we privilege with page space is a product of our inability to “say it all,” and therefore every writing act requires the self-reflective question: what and how is this doing?

Importantly, this short piece elucidates the central contention at work in the act of writing through an image that is quite literally an illustration—an atlas transposed over the town such that the map overwhelms the very territory to which it should be subordinate. After all, a map is an instrument used to condense, a tool for imagining a landscape too vast to be grasped.

While Borges speaks of a visually rendering, we can imagine how text might map over this territory, as well; a scroll of writing that articulates the minutiae of the landscape to the point that the description makes obscure the space it is supposed to be illuminating. Borges’s choice to make the town’s intelligent mistake one of over-relying on the “science” of cartography is what places the story firmly in the realm of satire; in trying to make their imitative map as verisimilar as possible, they ultimately obscure reality with artifice.

*

In her 1932 address to the Society of Typographic Designers titled “The Crystal Goblet, or Printing Should Be Invisible,” Beatrice Ward introduced one of the most enduring metaphors about the relationship between type and text:

Imagine that you have before you a flagon of wine. You may choose your own favorite vintage for this imaginary demonstration, so that it be a deep shimmering crimson in colour. You have two goblets before you. One is of solid gold, wrought in the most exquisite patterns. The other is of crystal-clear glass, thin as a bubble, and as transparent. Pour and drink; and according to your choice of goblet, I shall know whether or not you are a connoisseur of wine. For if you have no feelings about wine one way or the other, you will want the sensation of drinking the stuff out of a vessel that may have cost thousands of pounds; but if you are a member of that vanishing tribe, the amateurs of fine vintages, you will choose the crystal, because everything about it is calculated to reveal rather than to hide the beautiful thing which it is meant to contain.

*

The potency of the literary arts depend on the voids we leave between and around and among what we privilege with page space. But the unsaid only works if it is productive, not protective; it must reveal while it contains, like a wine glass or a map.

Maurice Blanchot notes in The Writing of the Disaster that the disaster “is what escapes the very possibility of experience—it is the limit of writing. This must be repeated: the disaster de-scribes.”

If the unsaid is an equal agent in the meaning made on the page, then we have to ask ourselves, as Percival Everett does: “What is the performative force behind the act I am committing in these brief pages?”

*

What am I trying to say? my students asked me and I told them that wasn’t the right question. The better question—the question all of us need to be interrogating every time we place pen to page—is not about what we are trying to say, but what we are choosing not to.

And so, as we navigate these last days of the year 2015, a year full of all kinds of unlanguagable events, let us ask ourselves and then let us face our answer:

What are we trying not to say?

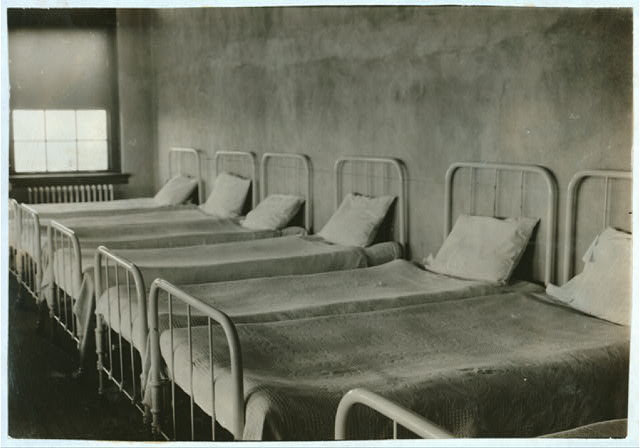

Image: “Crowded dormitory (one wall) in Training School for Deaf Mutes. Sulphur, Oklahoma.” by Lewis W. Hine, 1917. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Online Catalog.