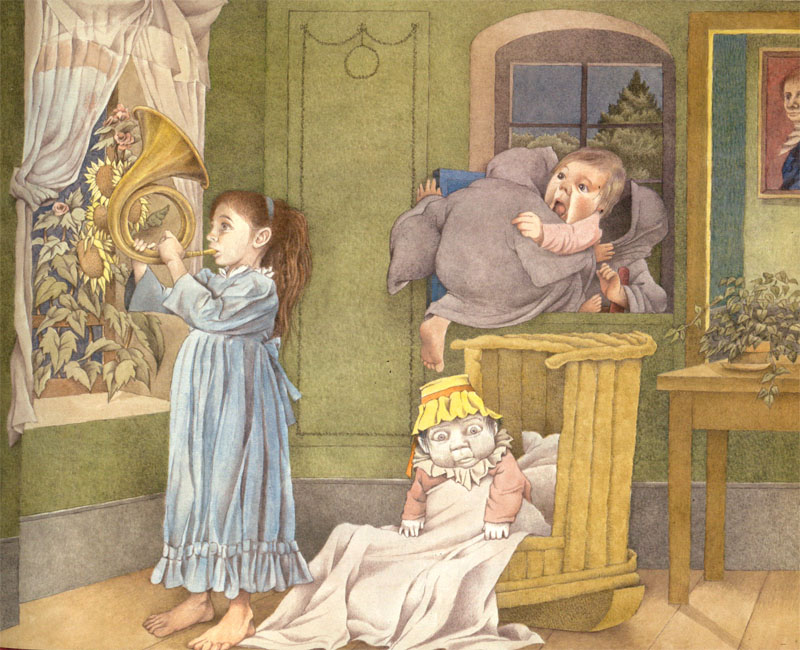

It’s Maurice Sendak’s textures that get me: in Outside Over There, my favorite of his books since I was a child, I am drawn again and again to the thick, shadowy folds in the fabrics of the clothing his characters wear: the mackintosh, belonging to her mother, the girl Ida puts on to go outside over there and rescue her baby sister from goblins; the cloaks the goblins wear while they steal the sister and replace her with a baby made of ice.

The books I read before I was old enough to read by myself loom almost as vividly as real memories. The most prominent are from the time when I was not totally illiterate, but still best trusted an adult to unlock the words on the page, leaving me to focus on the separate, often richer story of the pictures.

When I graduated from college, my first job was an AmeriCorps year at a literacy organization that provided libraries of children’s books to community-based organizations around Boston. That year, I read hundreds of picture books. Just as it has done in other countries and at other times, the picture book holds an elevated status for some of America’s most accomplished writers and illustrators: artists like Ana Juan, Kadir Nelson, Jon J. Muth, Chris Raschka, and Ed Young became some of my favorites. Students who were unsure about their reading skills, we told educators, could still look at a rich page of pictures and invent a story to go with them, or use the pictures to guess what would happen next.

Sometime during the year, I remembered Ida and her sister, and sure enough, we had a copy of Outside Over There in our office library. As part of our residence at each program, we designed a few lesson plans around books we thought kids would respond to, and gradually turned the planning over to the permanent staff members. We worked with mostly children of color, and so kept a bibliography of realist portrayals of diverse characters. Sometimes, as with Grace Lin’s Dim Sum for Everyone at a site where most children spoke Cantonese at home, culturally resonant picture books became favorites (after reading that one, the kids rushed to argue about the best of the dishes mentioned). But very young children, by and large, still prefer to live in a world of rich invention. By the end of the year, at an elementary site where every student was the child of Haitian immigrants or an immigrant herself, the book the kids begged for again and again was Walter the Farting Dog, a book with absolutely nothing to say about the Caribbean-American experience.

Could I read Outside Over There? I wondered again and again that year. Other books kept crowding it out–Chris Raschka’s glorious and nonsensical Charlie Parker Played Be-Bop, which provided a better introduction to both poetry and jazz than any tired anthology; the silly and loving I’d Really Like to Eat a Child (about a small crocodile who doesn’t want to eat bananas, a stand-in for “healthy” food), and a bevy of books that worked a lot like Saturday morning cartoons (by now, if there’s a toddler in your life, you’ve heard of the smash hit Don’t Let the Pigeon Drive the Bus). In a pre-Hunger Games era, I wasn’t sure if there was room for the themes and images of Outside: a dangerous journey a child takes on her own, unbeknownst to her mother, and for the nightmare-worthy goblins that carry a baby away. In the office, one colleague saw me reading it and sniffed that she never understood why we kept it around. It was too dark, and hard to relate to.

But Sendak knew that “relatability”–that charged word–was malleable for young children. Would it help every child to see heroes in his books that looked and talked like him? Yes. And in the milky wash of the book’s illustrations, Ida and her sister seem a transparent, old-world kind of white, and practically never speak directly. But the strength of the story is that it takes place both entirely in a child’s world, as in Where the Wild Things Are, but with the shadow of the darkest part of the adult world hanging over it. Adults aren’t present because Ida’s mother is “in the arbor,” looking very depressed indeed, and her father is “away at sea”—for commerce or contemplation, unclear, but not improbably for war. It’s no accident on Sendak’s part that to rescue her sister, Ida must go not to a spooky basement or attic or wood, but “outside over there”–over there being the sung euphemism for the world wars, as well as suggesting any location so far from home and so unknown that the only way of describing it is in terms of its distance from where you are.

This kind of fantasy, with a firm anchor in the real world, has the power of children’s real imaginative play, which, Sendak probably knew as well as D.W. Winnicott, does more than statically mirror their experiences: it also prepares them to feel capable in situations they fear they can’t control. This is the secret reason pediatric dentists keep denture-wearing toy bears and horses in their waiting rooms. In the over there Ida must venture to, only she, not an adult, knows the dangers and the possible tools for protection: she wears her mother’s mackintosh and carries her “wonder horn” (it fits in the coat pocket). When she plays the horn, the goblins transform from specters of nastiness into something slightly annoying but beloved and familiar: babies. The goblins wail at the music, a noise Ida associates with her sister and which brings her back to the world of her responsibilities.

Ida’s creative power not only generates a world with real dangers and unknowns, it conjures a problem she alone can solve. Beloved Max, in Where the Wild Things Are, conjures a world, but it exists in the empty spaces amid adult rules and routines (suppertime, bedtime), not in the more volatile space of grown-up absence and under the spell of grown-up conflict. Until the end of his life, Sendak, the child of Polish-Jewish immigrants, was haunted by the specter of the Holocaust–the dreadful, distant magic that gave his parents a family one day and none the next. Missing from Outside Over There’s text, but present in the illustrations, is ambiguity over where the figments of fear begin and end; early in the story, before they’re introduced verbally, goblins appear on pages alone (or beside a beautiful German shepherd–Sendak loved dogs). Ida disarms them in the end, but the pictures are clear: they could come from anywhere.

Who really gets to imagine? Not just to make things up, but to use imagination to navigate the world? As educational tools, illustrated books that give credence not only to children’s waking, real-world experiences, but also to the transformative power of their play, seem most often earmarked for privileged children, just as, for adults, the writing of fiction rooted in pure invention or methodical research, rather than autobiographical experience, is received most seamlessly when it’s done by white authors. (For the adult version of this discussion, see V.V. Ganeshananthan’s examination of the critical reception of Bill Cheng’s Southern Cross the Dog). Picture books like Faith Ringgold’s Tar Beach (which I’ll examine in more depth in a future post), which allows a protagonist of color to take the imaginative leap from the real world into a child-directed fantasy, are still too few, and get crowded out by educators’ desires to provide children with an authentic mirror or window into “real” human experiences (as if imagination wasn’t real). Why must a child choose between books that feature diverse characters and those that privilege her imagination–can’t we have all of the above, and lots of it?

In my next few posts, I’ll be taking a look at works of illustrated fantastical/magic realist fiction for very young readers that feature protagonists of color, and speaking with educators who have used those titles in their classrooms. (And I would love your suggestions!) For this series of posts, I’m focusing on full-color illustrated books geared at readers from ages 2-8, but I’d be happy to look at chapter books for slightly older readers. I think illustration is key, though, to the way a book gives a child license to make a story his own: in the deceptively simple words of Ed Young: “There are things words can do that pictures never can, and likewise, there are images that words can never describe.”

~

Postscript: When I describe Outside Over There to people who haven’t read it, they almost always say, “that sounds like Labyrinth.” The film was made five years after the book was published – Jim Henson “acknowledges his debt” to Sendak in the credits.

Image: Scene from Outside Over There, by Maurice Sendak.