One Sunday at work, in the middle of a series of lectures and panels–a day-long affair with no planned bathroom or coffee breaks–a man stands up. He does so while I am moving a lectern across the stage, and I think recognize him, even before he begins speaking, as someone who lives under the weight of New York City’s constant renovation, someone whose patterns have long ago been papered over. At the institution I work for, a Jewish archive and library whose existence spans nearly a century and two continents, people like this come all the time, or call on the phone. They’ve woken up and started looking, desperately, for places they’ve lost.

The man turns to face the audience and begins speaking as if to a stadium crowd, though there are barely two hundred people, some of them asleep. I worry about the next event starting late, a talk by a boyish professor who will first acknowledge his nursery school teacher sitting in the audience. The man explains, in a thick French accent that has passed through somewhere else, that he was born in Vilna, a city, I’ve learned since working at the institution, that saw its country disappear and a new one take its place, all while its own population, or at least the Jewish part, disappeared as if into holes in the ground. So it became a new city both because it suddenly belonged to a new country and because it had lost its memory, almost simultaneously. Unlike the way the family of an old person losing her memory can refer to her body as a physical portal to her former self, Vilna after the war and during the Soviet period seems to have lost both body and mind, its governors and inhabitants partially complicit in both losses.

I wonder what exactly is left after such a transformation. I think of an essay by a transgender writer about the ghost of the previous self left behind after a person transitions–how it never really goes away, how it can mingle and converse with the ghosts of the dead. The ghosts of lost cities must work that way, becoming dozens of sub-cities, living and yet not: the city of exiles, the city of the dead, the city of the forgotten, the city of the forgetters. Even today, scholars who study the city’s history chop Vilna’s name into a multiple choice question whose answers transport one across geopolitical borders and time–Vilna/Wilno/Vilnius.

The man doesn’t say any of this about the place he was born, although as soon as he begins speaking it is clear he is the product of a place with such a history, that he’s followed by the ghosts of the men he would have been in Jewish Polish Vilna, in Lithuanian Vilnius, if he had remained. Instead, he mentions that he has a book he thinks the audience may be interested in. (Around here, someone is always writing a book, or has just written one, as if a certain number of pages of Jewish memoir and history would build something solid enough to pass for the earth.) I am still on the stage, holding onto the lectern. I can’t see the man’s face. I can’t see the faces of the audience, either: the stage lights bear down and besides, I don’t want to look at them. But I know the palette that occurs when the skin becomes thin and the fluids of the body pool together, the body resting inside itself. The man continues, getting to a part of the story where his father is sent to prison. I can feel the crowd’s bewilderment, but also their joy–this kind of confessional transmission, more than scholars discussing the opening of the Soviet archives, is what they’ve come for, like worshippers at a revival. But I come down from the stage and put a hand on his shoulder. From what feels like a much greater distance than the actual distance separating our bodies, I ask him to sit down. But this distance, the distance that divides my attempt at cool professionalism from his need to confess, is part of the New York that’s tried to paper him over, to ghost him away. He won’t have that, and he lets me know it.

You can’t even give a survivor of Vilna two minutes of your time?

Please, sir, I say. We’re on a very tight schedule. I feel the words “tight schedule” like the taste of cigarette smoke in my mouth.

Yes, I can see you’re on a tight schedule, he sneers. I am your family, he seems to say without looking at me. For a moment, his eyes gain a kind of traction on mine. Some of the old women in the crowd, those who feel most at home when they are at a memorial, put their hands to their mouths and call out Let him speak!

You see, he says to me, bludgeoning me with the distance I’ve put between us, they want me to speak.

~

While interwar film footage of Jewish Poland plays in the darkened auditorium, I stand in the bathroom and watch myself cry. When I return, I scan the crowd for the man, but he is gone. A colleague tells me later that he stormed out, muttering to himself.

Later I say to my friend Sarah: when someone has gone through a terrible trauma, it must feel like that trauma knocks the whole world out of balance, trumps everything else forever. Like it is never not the right time to change the subject and talk about it. And in some ways, that person is right. They haven’t lived a normal life, they’ve been dealt a blow disproportionate to the blows a human is equipped to handle in his lifetime.

The ability to tell or receive such a story is a burden, a gift. As Muriel Rukeyser wrote, “if you refuse it / Wishing to be invisible, you choose / Death of the spirit, the stone insanity.” After many tellings, it’s possible that such a transmission also bears, and even enacts, some of the violence inextricable from the events. Such a story isn’t just a telling, but a happening.

That’s very generous of you, my friend says. An archivist, she has been working here longer than I have, handling with gloved fingers handwritten documents salvaged from the war, the very work of the hands of people who suffered the same or worse fates as the man in the auditorium. She says, I think he was just shilling for his book.

~

When war broke out in the institution’s founding city–the same city, Vilna–it relocated to New York, where it’s been ever since. Even after 75 years in America, a feeling of incompleteness, a sense of a phantom limb left in Europe, persists. Office apocrypha say that there are some documents in the archives which, due to the haste with which the founders smuggled materials out of the hands of the Nazis, are literally split in two, one half having spent its life greyly behind the Iron Curtain, and the other half having sailed into port at Ellis Island: a letter that starts in Europe and ends in America.

Years of researchers poring through the archive have never produced an actual example of a letter or other document’s missing half, and it seems exceedingly unlikely that such an example exists–more probably, the missing half of any letter found in America isn’t locked up in an un-catalogued post-Soviet archive somewhere, but simply missing. Yet the myth is appealing: if you are missing a piece of yourself, it must be somewhere, and imagining it makes its absence a little less. This ability we have to recognize the shape of people in their things, to make of an absence a presence, marks a fork in the road dividing the beginning of fiction and the beginning of history. Glimmering in the piece we have is the possibility of the other half, a reflection fading in and out. “And I will go back before my beginning / and be and not be / like a star / in water,” wrote the Yiddish poet Avrom Sutzkever from the Vilna ghetto.

When two of my colleagues tell me about this myth of the archives, I recall a story whose title and author I’ve forgotten–I have a blurry memory of reading it in Spanish, in a sunny kitchen in spring–about a man picking up a lost glove and having sudden access to the wearer of the other glove, who lives maybe across the city, maybe on the other side of the world. He doesn’t read her mind, or see her through some kind of wizard’s ball, but the single glove sends him into a rhapsody of memory or imagination, filling out the life of its partner’s wearer, inventing or reporting the details of what is otherwise just a glove someone else has dropped, searched for a while, and forgotten.

That’s all of the story I remember, and I have to invent the rest.

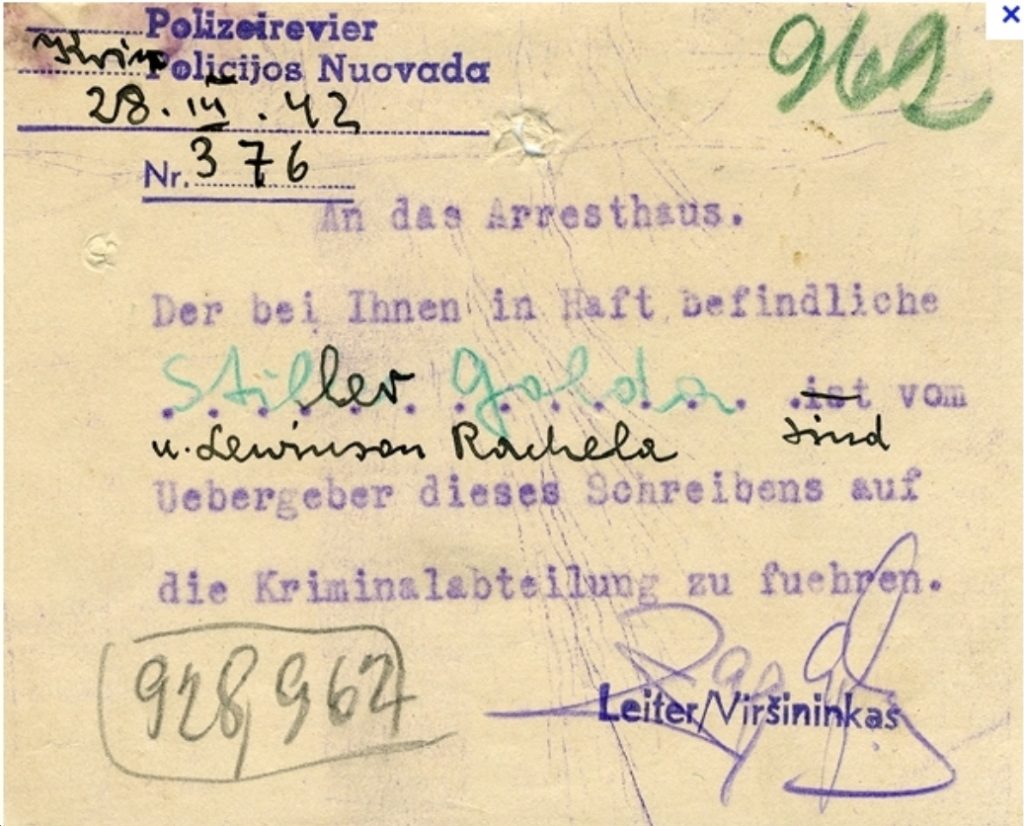

Image: 1942 document courtesy of Chronicles of the Vilna Ghetto.