After my grandmother died, my mother was given all of her possessions. There was a lifetime of sentimental trinkets, of furniture that had never gone a day without its dust-protecting plastic jacket, and of strange redundancies. My grandmother left her with four refrigerators, three televisions, and twelve swatches of fox fur. My mother complained to a friend that she had no idea what to give up, what to throw away, what to burn. There was no talk of keeping.

Through my elementary and middle school years, I spent three summers in my grandmother’s apartment. The space is simultaneously cast in light and shadow, as any childhood home is. I still see clearly the plastic plants she had me sketch for art class; hear the crackling oil as my grandmother pan-fried eggplant fritters; feel the frustrating heat as my grandmother refused to plug in her air-conditioners, which hung like silenced deities on the walls. A place both ordinary and magical, a place where I grew up.

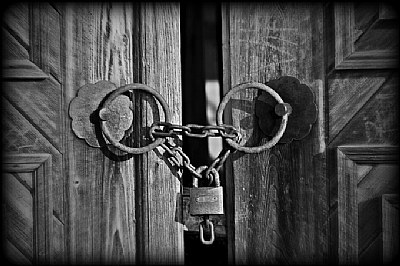

I consider a farewell incomplete if I am not able to say goodbye to the objects and spaces that made the experience whole. After breakups, after the end of the school year, after the lease runs out, I sit in couches, lie down on beds, feel the paint on the walls and think, this is the last time. With my grandmother’s apartment, Apt 1203, I did the usual routine. But my grandmother has too many things.

My grandmother was not present when I said goodbye to all of the familiar parts of her home. I had already said goodbye to her, at the hospital—not a “forever,” adieu sort of goodbye, but one that pretended, and almost felt, like a normal one. I was going back to America. The summer was over. Maybe I would see her next summer. Maybe she could even come to visit me. We hugged. Her grip was strong and her eyes were as fierce as always. We did not say “I love you” because we never had. She was the most ferocious woman I’d ever met.

When my grandmother died, my mother had been taking care of her for four months. They had not been close. Their relationship was difficult. But on the day my grandmother died, my mother told me that she had no regrets. In those four months, she had cared for my grandmother like she was her own child. She’d clipped her toenails, washed her body, and distracted away her tears. As a tribute, my mother also told me about how, after my grandfather died, my grandmother had reconnected with another man she’d known when she was a young woman. He was, in my mother’s and grandmother’s words, a very romantic man. They had met most afternoons in the park near my grandmother’s place where they would sit on a bench and talk. My grandmother, protective against more loss, never wanted more. She did not let anyone tell him she was in the hospital. He might still be in that park, waiting on their bench. I love this story because, under a certain light, it can seem like a sad story, but if you knew my grandmother, and you knew not only how stubborn and controlling and domineering she was but also what made her that way, then you would also love this story because you would understand that a happy ending is one with no regrets, and that no regrets, for my grandmother, meant taking control of whatever you could.

One regret: I should have taken photos of my grandmother’s apartment. The kitchen, the two bathrooms, the enclosed balcony, the bedrooms, the hallway with the mirrors—these pictures are clear in my head, but they won’t always be. Taking pictures is the opposite of saying goodbye to a place. Taking pictures means having pieces of paper, meaningful only to me, that I will never be able to throw away. Pictures that I will take from apartment, to apartment, from house, to house. Until, one day, my own children, facing my mountain of junk, all glittering with unknown significance, will look through these photographs and wonder, why in the world did she keep this?

But I have saved the next generation this one, small hassle.

One regret, in the aftermath, is not so bad.