This summer I read two books about music, equally fascinating on their own and even more so in combination. The first, Elijah Wald’s Escaping the Delta: Robert Johnson and the Invention of the Blues (Amistad, 2004), pushes back against the well-known and oft-repeated legend of Johnson as the best, most original, and most influential of the Delta bluesmen recording in the 1920s and ’30s, and argues instead, by looking closely at both the charts and the records themselves, that the way we—a largely white and after-the-fact audience—understand the history of the blues often bears little relationship to the actual details of that history. In fact, according to Wald, Johnson was little known in his own day, and even if we dig a little deeper and seek out varyingly available recordings of artists like Big Bill Broonzy, Kokomo Arnold, or Hacksaw Harney, we have to remember that we can only listen to the recordings that were made, i.e., the recordings that northern executives predicted most salable, which represent only a fraction of what these artists wanted to, could, and did play for audiences outside the studio.

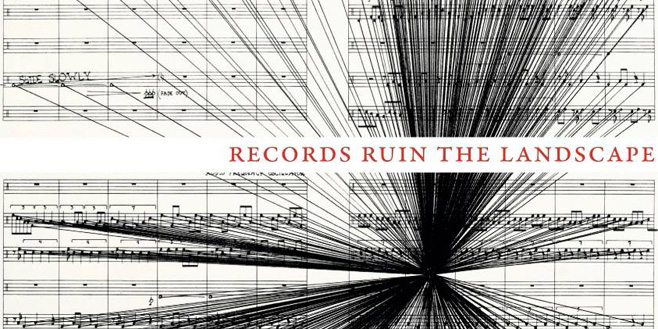

The other book, David Grubbs’s Records Ruin the Landscape: John Cage, the Sixties, and Sound Recording (Duke, 2014) in many ways continued the conversation about cultural memory and the history of recording begun in Escaping the Delta. Here Grubbs looks at the world of experimental or “new” music, whose narrative, like that of the Delta blues, has been informed (or deformed) by the technical logistics, financial considerations, and aesthetic ramifications of sound recording. Not only did the un-marketability of this difficult, abstract music keep much of it unheard in its time, but certain artists and composers also considered the nature of their work unsuitable to and even undermined by sound recording and reproduction—for example Cage’s “indeterminate” compositions, with each performance of a given piece unique, more tool than object, more “camera” than “photograph,” or British guitarist Derek Bailey’s works of “free improvisation,” which when recorded, removed from the context of their one-off making, and issued for repeated listening, risk spuriously coming to seem “composed” or worse, becoming background or “mood” music. As Grubbs quotes Bailey as saying: “If you could only play a record once, imagine the intensity you’d have to bring into the listening.”

The other book, David Grubbs’s Records Ruin the Landscape: John Cage, the Sixties, and Sound Recording (Duke, 2014) in many ways continued the conversation about cultural memory and the history of recording begun in Escaping the Delta. Here Grubbs looks at the world of experimental or “new” music, whose narrative, like that of the Delta blues, has been informed (or deformed) by the technical logistics, financial considerations, and aesthetic ramifications of sound recording. Not only did the un-marketability of this difficult, abstract music keep much of it unheard in its time, but certain artists and composers also considered the nature of their work unsuitable to and even undermined by sound recording and reproduction—for example Cage’s “indeterminate” compositions, with each performance of a given piece unique, more tool than object, more “camera” than “photograph,” or British guitarist Derek Bailey’s works of “free improvisation,” which when recorded, removed from the context of their one-off making, and issued for repeated listening, risk spuriously coming to seem “composed” or worse, becoming background or “mood” music. As Grubbs quotes Bailey as saying: “If you could only play a record once, imagine the intensity you’d have to bring into the listening.”

Not suspecting that I was adding a crucial third dimension to my reading, about the same time this summer for my aunt’s 70th birthday I burned a CD of the top three Billboard hits each year from 1959 to 1965, guessing that these years would mark a formative period of her youth, one susceptible to the infections of pop music. The first song I downloaded was Johnny Horton’s goofy and admittedly contagious “Battle of New Orleans.” Oh God, I thought, wincing as I paid to introduce this thing into the immaculate and proudly curated space of my iTunes. I had neither the desire nor the time to listen much as I went on downloading—Lloyd Price’s “Personality,” the Jim Reeves’ “He’ll Have to Go,” Bobby Lewis’s “Tossin’ and Turnin’”—disconcerted for having thought myself a fan of this period of music but recognizing relatively few of its most popular artists and songs, relieved when in 1964 and 1965 I landed in familiar territory with early Beatles, Motown, and the Rolling Stones.

We listened to the CD in the car on a long drive to lunch in New Hampshire, and for my aunt the present-day experience of these 50-year-old songs was very different from mine, of course. Had I spent so much time lately exploring the harsh topography of the musical avant-garde and contemplating the various implications and distortions brought about by “the archive” that I had forgotten what it was to be transported suddenly into the past—an intimately personal, charged past—by a pop song half-heard dozens and dozens and dozens of times, peripherally? These aren’t the significant self-other projections of genres crossing racial lines but experience stowing itself away where the intellect can’t taint it, in songs that seem content to drift into the background and wait to perform their magic act. Whereas John Cage forces us, if only for four and a half minutes, to give ourselves over to whatever’s offered by the present moment, Johnny Horton allows us to preserve a composite present, loaded with emotions—both pursuits noble and necessary, I think. And let Derek Bailey scoff, but the word “intensity” applies perfectly to my aunt’s reaction to the first quaint banjo notes and snare rolls of “The Battle of New Orleans.”

We listened to the CD in the car on a long drive to lunch in New Hampshire, and for my aunt the present-day experience of these 50-year-old songs was very different from mine, of course. Had I spent so much time lately exploring the harsh topography of the musical avant-garde and contemplating the various implications and distortions brought about by “the archive” that I had forgotten what it was to be transported suddenly into the past—an intimately personal, charged past—by a pop song half-heard dozens and dozens and dozens of times, peripherally? These aren’t the significant self-other projections of genres crossing racial lines but experience stowing itself away where the intellect can’t taint it, in songs that seem content to drift into the background and wait to perform their magic act. Whereas John Cage forces us, if only for four and a half minutes, to give ourselves over to whatever’s offered by the present moment, Johnny Horton allows us to preserve a composite present, loaded with emotions—both pursuits noble and necessary, I think. And let Derek Bailey scoff, but the word “intensity” applies perfectly to my aunt’s reaction to the first quaint banjo notes and snare rolls of “The Battle of New Orleans.”

Track after track my aunt sang and danced in the back seat, laughed and “oohed.” And it was the theme from A Summer Place, probably the blandest song of them all by my standards, that brought my aunt to tears as she recalled an early movie date she’d been on with a boy named Ruddy. Several songs later, Ruddy had broken her heart. Minutes in the car were moving her through years of her life with impressive power and efficiency. And it was moving. But by the time we got to “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction,” my aunt’s enthusiasm for the CD seemed to have flagged a little—maybe I had mis-guessed which were the most impressionable and absorbent years, maybe extended acts of nostalgia just take it out of you—but now I had something even more interesting to ponder and wonder at than the indeed telling shift of popular tastes from 1959 to 1965.