“…Did you note the propensity of second/-ary, lesbian, Post, identity transsexuals to limn greek mythology?/Was Anne Carson a transsexual, was Lesbos?”

—Trish Salah from Lyric Sexology, Vol 1

*

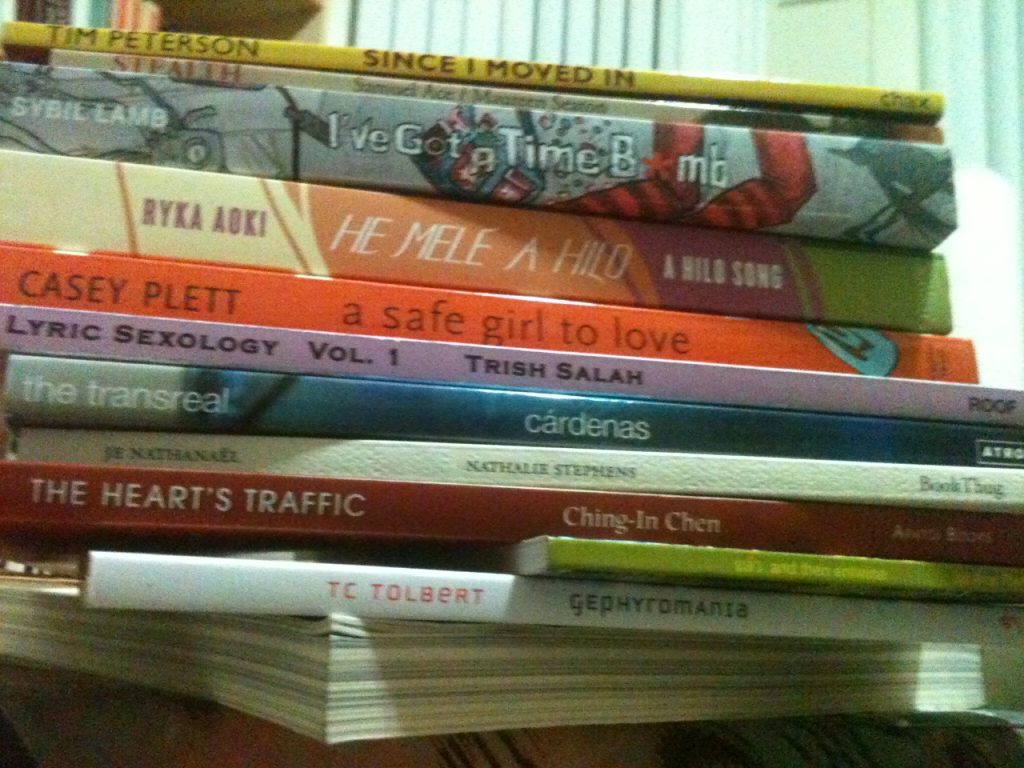

In her bio, author and editor Trace Peterson lists her two favorite things: sex and literary criticism. While many other creative writers don’t go in for it (criticism, that is), I share Trace’s enthusiasm. Sometimes, I just want to light a few candles and analyze literature. Case in point, this stack of books on my chair, some of which I’ve read and re-read, some skimmed, some not yet cracked. I want to read and delve into the complexity of their language. Instead I find myself having written a piece mainly about politics and context. I can’t resist the impulse to explain. Beyond the manifold pleasures within the text, I get a thrill from being able to participate in helping texts and authors find their audiences.

At the Writing Trans Genres conference that I discussed in my previous post, there were several conversations about the reception of work by trans and gender variant writers. Some of us may produce difficult work, but any work we produce faces interpretation by means of our ‘difficult’ genders. We’re frequently called on to account for ourselves in institutional and social contexts. As we achieve a wider audience, this demand carries over from our persons to our work—often inextricable in the popular imagination. I vacillate between explanation fatigue and an awareness that if I don’t try to represent myself, and speak about (but not for) my community, others are willing to step in and do it for me. I do this with full awareness that there will never be a definitive essay about trans and gender variant writers, because our experiences and identities range widely (although there’s a lot of material for basic self-education).

After this post, I’m going to give myself a break to finish my sequence of tarot poems and read these books — anything but be the explainer for a while, however useful it might be. As Paula Mendoza notes in her post Difficult Poetry and Sarah Vap’s End of the Sentimental Journey, “…‘use’ and ‘relevance’ often reveal themselves to be no more (or less) universal than one’s personal experience, tastes, and preferences.” Pair this with Ryka Aoki’s remark, “Don’t confuse what you want to hear with what I want to say.” When a trans person decides to educate others about their life, it is a risk for them, a gift for you, and not necessarily in line with your expectations or ‘accepted narratives,’ such as coming out. Visibility unites the emergence of a literature and the coming out process. In order to talk about the emergence of trans lit, I find that I have to talk about time as well. Emergence (again, like coming out) presupposes a linear trajectory. To say that a literature has emerged is a useful fiction; a shorthand for a host of possibilities, which span many verb tenses and possible relations to existence.

In his essay on contemporary choreographer Sean Dorsey’s dance work “Lou” (2009), about transsexual activist Lou Sullivan, “Embracing Transition, or Dancing in the Folds of Time” Julian Carter explores this notion:

Anticipation, retroflexion, and continuity co-exist in the same body, at the same moving moment of space and time. Transitioning subjects anticipate a gender content they generate recursively out of their physical medium’s formal potential in relation to the context of its emergence. One might say transition wraps the body in the folds of social time. (28)

What happens when we attempt to understand individual writers in the context of the idea(l) of a community of trans and gender variant writers? What happens when we attempt to consider the community of trans writers and its place among trans people in general? Within the community of writers in general? The coexistence of multiple modes of temporality in individuals resolves into increasingly abstract and imaginal communities whose deployment forms the precondition for historical time.

In one of the panels at WTG, Imogen Binnie expanded on some points from one of the posts on her blog, Keep Your Bridges Burning, in which she draws on the introduction to Jean Baker Miller’s Toward a New Psychology of Women. Miller posits a system of stages through which the writings of an oppressed group progresses. My notes from Binnie’s summary:

1. “Actually, we are just like you”

2. “That’s cis-suprematist bullshit”

3. “Creating our own lexicon”

The first item on the list refers to the initial stage of the reception of work by trans and gender variant writers, in which the struggle for any serious attention demands the use of mainstream formal and narrative devices. The second captures the inevitable reaction against this practice. The third represents where we are today, or as Binnie suggests in her post, where we are stalled today and, perhaps, a generative site of potentiality.

Some of the fiercest debates within, or unfortunately sometimes between queer and trans communities focus on language. Who should or should not say the t-word?To what extent should trigger warnings be incorporated in artistic or academic contexts? (see also) The tenor of these debates may confuse even those with a stake in them. Perhaps a better question would be: what are we talking about when we talk about terminology? Binnie again, to clear it up: “…how are we going to talk about the ways trans women are marginalized within trans and queer communities if we can’t even get to square one with regard to language? How do we talk about privilege when you can’t even tell that you’re erasing me with yours?” This analysis draws heavily from the work of Julia Serano, author of Whipping Girl: A Transsexual Woman on Sexism and the Scapegoating of Femininity and Excluded: Making Feminist and Queer Movements More Inclusive, who coined the term transmisogyny, to point to the specific intersection of oppressions that trans women and other gender variant DMAB (designated male at birth) folks face.

These debates, contentious though they are, rest on assumptions of shared trans identity (also called the trans umbrella), but there is no umbrella big enough to cover all of us. At WTG, Gein Wong talked about the experience of googling trans history and finding Renée Richards, Kate Bornstein, etc.—the image of what transgender is in the mass media for the past ~60 years. In contrast, she presented several indigenous gender roles, such as fa’afafine, who have a special role to take care of elders, and Muxe, saying that this research can help affirm some gender-variant histories as magical or spiritual; that is, part of society and not counter-cultural.

The same racial hierarchies that structure social inequality in society as a whole pervade trans communities. These communities are arguably more vulnerable to this logic because of the persistence of the idea that oppressions are somehow equivalent or interchangeable. A post by Latoya Peterson on Racialicious turned me on to Andrea Smith’s essay, “Heteropatriarchy and the Three Pillars of White Supremacy”, featured in Color of Violence: The INCITE! Anthology. Smith discusses the obstacles inherent in prior approaches to women of color or people of color organizing with respect to the diversity within organizations or coalitions: “First, it tends to presume that our communities have been impacted by white supremacy in the same way. Consequently, we often assume that all of our communities will share similar strategies for liberation. In fact, however, our strategies often run into conflict” (67). Smith writes that one source of the conflict “…is that we are seduced with the prospect of being able to participate in the other pillars” (69). Her stated goal is, “…to ensure that our model of liberation does not become the model of oppression for others” (69). I believe that some aspects of Smith’s model, like Miller’s, can be applied to the trans and gender variant community, inasmuch as we are a diverse group with a power differential that makes us vulnerable to political co-optation.

Trans literatures, in that they can be spoken of collectively, have a strong grounding in activist traditions. This makes sense, considering the persistent disenfranchisement of trans folks. Given, however, that a space is opening up for more trans writers and publishers—what shall our relationship to this tradition be going forward? We might acknowledge, as a start, that trans folks are not a uniform group with uniform political and literary goals. I’m excited to think about what might emerge when disparate groups can make common cause—perhaps even a more liveable life for a greater number of trans and gender variant people? That’s why I’m giving so much space here for politics: we need to be able to exist and thrive as people, in order for our literatures to fully come into their own.