When I was an undergraduate at a small liberal arts college in the desert outskirts of Los Angeles, one of the literature professors I most admired referred to me as “an intensely serious student.” I had taken his 19th Century Russian Novel course that semester. Was I serious? In manner, probably not. But in my soul? In my mind? Yes! I believed so. And the aesthetics of seriousness certainly appealed to me–Turgenev’s gorgeous sentences, Dostoyevsky’s heft–such that I always chose the most beautiful library on campus, not the one closest to my apartment, in which to read and write. I was flattered by the compliment, but more so, I felt vindicated, rightfully seen.

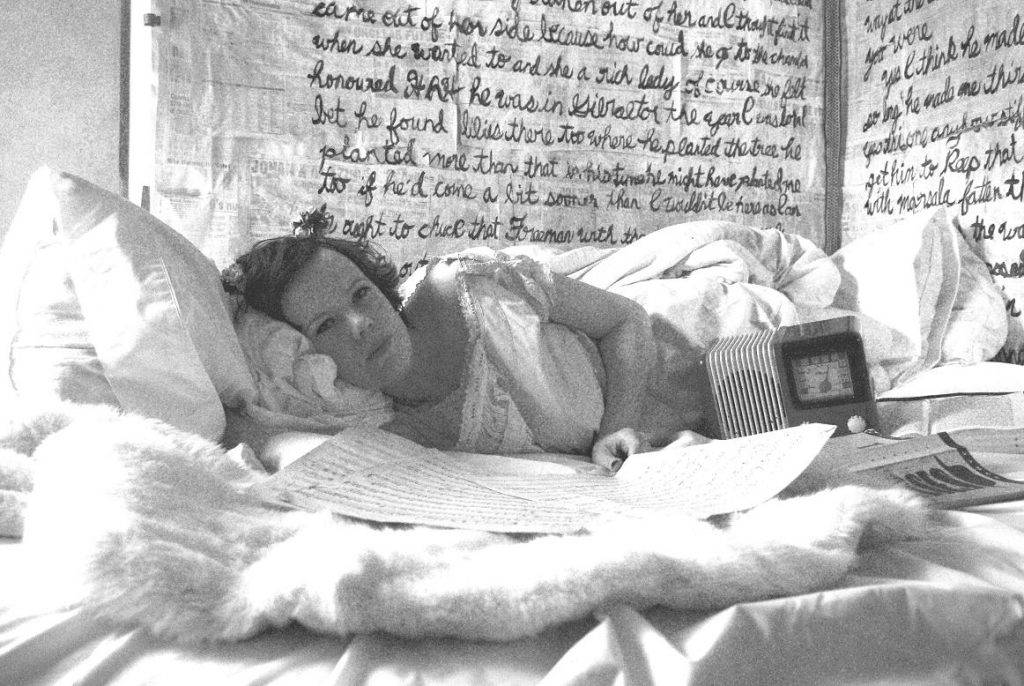

Those days, I cut my hair in 1920s styles, with kitchen scissors on the patio of my apartment, aided only by a hand mirror. I wore 75-year-old lace nightgowns as sundresses. I drank a lot of red wine and I scowled at the girls in stretchy shorts and at the boys without shirts, who played games with the object of drinking beer I deemed terrible, who listened to music I deemed terrible, who studied finance or accounting, or something else I deemed terrible. At an honors dinner, a wealthy donor to the college asked me if I thought the creative writing thesis option, which I had taken, amounted to “the easy way out,” and I nearly spit on him, despite my financial aid scholarship. I was angry about the things that bored me, banished them from my proximity. Indeed, I was serious. I wanted to surround myself with heavy, ornate things, elaborate conceits; perhaps that’s why I enrolled in a Joyce seminar the last semester of undergrad. Southern California, and I was 21 years old. Primed, raring, for Ulysses.

The professor of the Joyce Seminar had incredibly long hair and wore a different pair of stylish leather boots to every meeting. She spoke of attending Joyce conferences all over the world–which sounded outrageously glamorous to me. She introduced us to the smutty love letters between Joyce and his wife Nora. “My little shitbird.” Nobody had ever called me that. She seemed to have read everything, and thus I imagined that she lived, as Joyce wrote, near to the wild heart of life, in Ireland attending Joyce conferences in her fabulous boots, dipping down to southern Spain to write in the sun with a bottle of wine and cavort with beautiful intellectuals, writing dazzling papers on international flights, and having her hair deep conditioned and brushed in the meantime. Hers was the life that would be mine in the next decade. In my thirties, I thought to myself, I will have read everything and I will have a chestnut mane. During one of her lectures I made an idle note to read every volume of In Search of Lost Time over the summer.

Nearly every student in the class purchased a defective Gabler’s Ulysses. Loose pages fell from the classroom’s books in simultaneous clumps that seemed timed by some great watch. A bad batch of glue. We wrote to the publisher en masse, and received replacement copies, nearly as badly bound as the originals.

We read the Ellmann biography of Joyce, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Dubliners, and Ulysses. She told us to save Finnegan’s Wake for the summer. One guy with pompous hair talked too much, which is not an unfamiliar phenomenon in a literature seminar, and which I only found intolerable when he interrupted the professor. I committed her gestures and phrases to memory. She complimented another student on her skirt, which she called “heliotrope, a Joyce color.” “Far too much white grape,” she said, after taking a sip of a student’s smoothie (Why? I suppose it was offered) at the beginning of class.

Once I came to the Joyce professor’s office hours to discuss my term paper and mounted what I thought was a convincing, though breathless, argument for the confluence of certain of Matisse’s line drawing nudes with aspects of Molly Bloom’s physicality. She frowned kindly. I pulled a sheaf of JSTOR photocopies from my dingy canvas tote bag and gestured. She put the matter succinctly: “There’s a lot of crap out there.”

She told me instead, to study the text. To re-read Molly. And to listen to it. I watched Molly’s soliloquy performed by Fionnula Flanagan and rewrote my term paper proposal. Since then, I’ve heard other actors perform Molly. Marcella Riordon, Caroid O’Brien, Aedin Moloney. This week I revisited the videos to hear Molly’s voice. “I’d like to get some of those red slippers,” Molly said; and, “I’d love a big juicy pear now to melt in your mouth.” This week, in the days before and after Bloomsday, another Molly Bloom has shown up in my searches–some ruthless poker runner, very tan. The wonderful thing about Joyce’s Molly Bloom is imagining her words in the mouths of many different women–this bronzed celebrity poker princess might also utter: “What kinds of flowers are those they invented like the stars?” Or another great line: “A woman, whatever she does, she knows where to stop.”

I’m in my thirties now, adjuncting, working in a bookstore, and I haven’t yet read all of Proust. I tell my students, the brightest and most lost amongst them, to re-read carefully. When I was around their age, between 17 and 21, I was certainly not as serious as I wanted to be. I whiled away many long afternoons, sitting beside a sparkling swimming pool on campus. For some of those years I owned a fake ID that permitted me to drink fruity liquors to excess. Once, I made out with the wrong boy in the beautiful library. Enchanted by postmodern whimsy, I took “the easy way out” in several passages of my creative thesis, using cheap typographical tricks I cringe as I recall now, rather than writing like a sensible, self-possessing artist.

Southern California, I was 21. Full-blown Spring, the vertiginous experience of reading the last page of Ulysses in my apartment, the door cracked open, my roommate’s Brazilian samba beats thudding across the gray carpeted hallway.

I was a Flower of the mountain yes when I put the rose in my hair like the Andalusian girls used or shall I wear a red yes and how he kissed me under the Moorish Wall and I thought well as well him as another and then I asked him with my eyes to ask again yes and then he asked me would I yes to say yes my mountain flower and first I put my arms around him yes and drew him down to me so he could feel my breasts all perfume yes and his heart was going like mad and yes I said yes I will Yes.

Here, the accumulation of the book’s loose pages seemed to ripple in the propulsive breath of that closing soliloquy; my wild heart leapt. Molly Bloom–adulteress, Gibraltar-born opera singer, pure fiction–knew something about me. Again, I was seen, and vindicated. This is what I wanted, this serious desire, this rapid, shining certainty, breasts all perfume, this multitudinous, heliotrope-flecked life.