In planning a course on the Middle East Through Graphic Novels for the fall, I was surprised by the number and quality of the different works, as well as how often these books could be used as teaching tools. The Middle East, with its mythic and socio-political significance, has become a great source of inspiration for many important graphic novelists.

A quick thematic survey follows. Naturally many other important features in these works are worthy of consideration, such as stylistic and formal elements. Maybe in a future post I will look more closely at one of the books or discuss the different aspects of the graphic novel.

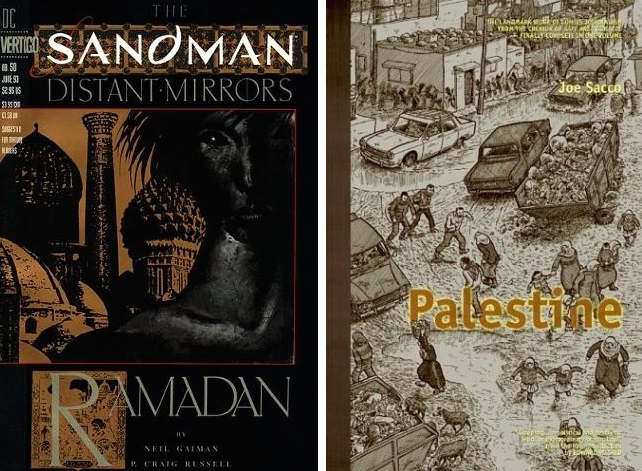

In 1993, two important but very different comics dealing with the Middle East were published. One was by the revered Neil Gaiman. The Sandman #50: Ramadan is a beautifully rendered Orientalist tale set in Baghdad with Caliph Haroun Al Rashid, his carnal harem, Lord of Sleep, and a magic carpet. It remembers the majestic past of the city against the devastation after the Gulf War bombing. The other is by Joe Sacco, a comics journalist who spent two months during 1991-92 in the Occupied Territories. Sacco wrote a series of nine pieces reflecting on the first intifada that were collected into the graphic novel Palestine in 1996 and won the American Book Award.

The extremely influential graphic novel by Satrapi followed the success of Sacco’s work. Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood, first published in France in 2000 and then subsequently in United States in 2003, focuses on the Iranian revolution. Next came The Photographer: Into War-torn Afghanistan with Doctors without Borders, the story of the photojournalist Didier Lefèvre’s 1986 trip to Afghanistan during the Soviet war. It first appeared in three volumes, also in French, between 2003 and 2006.

The books started a trend in which major social-historical issues are discussed through the author’s personal experience. Travelogue, memoir, and journalism are combined in something akin to a For Beginners graphic non-fiction, allowing personal narratives and character interactions to make sense of social events and conditions. The works are neither essays nor fiction.

These graphic novels appeal to the exotic and tackle difficult subjects, entertaining as they teach. They confer on the consumer what Gillian Whitlock in Soft Weapon: Autobiography in Transit calls the status of “an enlightened, sympathetic, and politically correct individual” (15). Through subjective truths, the authors “personalize history and historicize the personal” (20). The works also reinforce the role of the individual as representative, which reinforces the role of democracy and the bourgeoisie that stands for the greater society and the dominant American ideologies.

The narrator frees the story from needing to be purely objective and factual, not that anything can be purely objective. Yet the narrator’s experience as evidence also makes the reader feel like they are getting closer to the truth. The autobiographical characteristic increases the empathic identification in the reader.

Examples of the popularity of this type of graphic novel can be found in a number of recent books on Palestine and Israel. In the past six years, at least seven books have tackled this troubling area from different perspectives.

Sacco’s Footnotes in Gaza (2009) continues his journalistic reporting on the Palestinian experience. This time his character is less prominent and the graphics more straightforward. He aims to bring to light two historical footnotes, the massacres of 1956 in Khan Younis and Rafah. Yet he is also aware of the challenges of his undertaking. His interviewees and friends question the purpose of writing about something that happened so long ago. They want him to report on current events–the bulldozing of homes and the expansion of settlement. Sacco also questions the limitations of his finding, wondering how one can determine what happened when all you have are the fallible memories of survivors.

Memory and remembrance are the topics of Waltz with Bashir as well. The narrator and Israeli author Ari Folman is trying to recall what happened during the war in Lebanon. The shadow of the 1982 massacre at Sabra and Shatila looms in his psyche. As an Israeli soldier who was in Lebanon, he wonders why he can’t remember. While the Israeli Defense Force (IDF) was not directly responsible for the massacre, they aided the Phalangists and were aware of what was going on but didn’t do anything to stop it. Can we blame Waltz with Bashir for not providing enough historical explanation of the Lebanese civil war as others have done? Was it the indirect culpability that enabled the Israeli government to admit to wrongdoing? Or does this indirect involvement only raise the bar of guilt and responsibility for all of us who find ourselves on the sidelines watching the tragic conditions of the Middle East continue? The strain of needing to remember and the instinct to repress horrific incidents, something with which the Jewish history is burdened, haunts this frightening and powerful film (2008), which was later made into a less effective graphic novel (2009).

Jerusalem is the title of two very different graphic novels. Jerusalem: A Family Portrait (2013) by Boaz Yakin & Nick Bertozz is based loosely on Yakin’s family. In a sweeping cinemascope and with a large family cast, the novel presents different Jewish perspectives during WWII and the formation of the Israeli state. Yakov is not afraid of showing the dark side of the society. One can get a sense of how the social conditions and the vociferous extremes took hold; how the fervor of youth, desperation under oppression, and zealousness became the transformative forces of community. We watch/read how Avraham, a war hero who has become a communist fighting alongside Arab brothers in solidarity with workers and the oppressed and for independence, joins the Jewish army. The argument goes like this: stand with your family and community, for if Jews win, then you won’t be able to look the community in the eyes, and if the Arabs win, then you will be killed (214).

Jerusalem is the title of two very different graphic novels. Jerusalem: A Family Portrait (2013) by Boaz Yakin & Nick Bertozz is based loosely on Yakin’s family. In a sweeping cinemascope and with a large family cast, the novel presents different Jewish perspectives during WWII and the formation of the Israeli state. Yakov is not afraid of showing the dark side of the society. One can get a sense of how the social conditions and the vociferous extremes took hold; how the fervor of youth, desperation under oppression, and zealousness became the transformative forces of community. We watch/read how Avraham, a war hero who has become a communist fighting alongside Arab brothers in solidarity with workers and the oppressed and for independence, joins the Jewish army. The argument goes like this: stand with your family and community, for if Jews win, then you won’t be able to look the community in the eyes, and if the Arabs win, then you will be killed (214).

Jerusalem: Chronicles from the Holy City (2012) is another travelogue by Guy Delisle who writes on distant and foreign places. Delisle’s aloof, outsider perspective allows other western readers to identify with him. He confronts the situations as a non-religious visitor having to deal with the stereotypical religious customs. He explores Jerusalem, loosely commenting on the political situation without trying much to empathize or explain the roots and purposes of the customs. So it is not surprising that many critical reviewers on Amazon see his reaction to Sabbath, Passover, and Purim as offensive. They even go so far as to call him an anti-Semite. What these reviewers miss is that he does the same thing to Islam, whether it is his frustrated reaction to the early morning call for prayer or his tactless and provocative presentation of nude drawings of women for his traditionally veiled students. He also complains of the Palestinian neighborhood where he lives without a park, playground, and outdoor café and finds all his desired western amenities in the Jewish quarter. I could easily list a dozen similar examples. The biased readers, Jew or Muslim, may see these perspectives as natural when it comes to cultures to which they have no attachment, but offensive to their own faith.

The next three books are written by Jewish Americans about their relationships with Israel. As a response to Sacco’s Palestine, Miriam Libicki has been writing Jobnik!, a series of autobiographical comics about her experience of enlisting in the Israeli military. Her work is more a coming-of-age story with the fear and danger of terrorism in the background than a study of the political issues. It is meant to humanize the Israeli military by telling the stories of the soldiers.

The next three books are written by Jewish Americans about their relationships with Israel. As a response to Sacco’s Palestine, Miriam Libicki has been writing Jobnik!, a series of autobiographical comics about her experience of enlisting in the Israeli military. Her work is more a coming-of-age story with the fear and danger of terrorism in the background than a study of the political issues. It is meant to humanize the Israeli military by telling the stories of the soldiers.

Sarah Glidden’s How to Understand Israel in 60 Days or Less (2012) details her experience as a birthright tourist visiting Israel for the first time. Birthright tours are funded by Jewish organizations in partnership with the Israeli government for North American Jews age 18 to 26. From the start, Glidden is very honest and critical of the Israeli government and continues to question various narratives she is told throughout the book. But she is also surprised that the Israelis she meets and the tour guides are more honest and critical. They are not espousing propaganda as she expected. She is repeatedly told that the situation is more complicated than she thinks (76, 118). Slowly, she begins to come around to empathize with Israelis and their concerns. One can say that the birthright tour was a success in its mission to strengthen the connections between Israel and the Diasporic community. This is no surprise for those familiar with ideas of Antonio Gramsci and Slavoj Žižek. The most effective way to teach ideology is not through overt propaganda, something that many Middle East nations have yet to grasp.

Not the Israel My Parents Promised Me (2012) is primarily a candid monologue by the influential underground comic writer Harvey Pekar, who was raised by Zionist parents. He questions the actions of the Israeli government and is censured as a self-hating Jew. To make his point, Pekar quickly goes through a great deal of Jewish history from Abraham to the present day. An interesting contrast can also be made with Glidden’s birthright experience here. When trying to immigrate to Israel, Pekar was refused because of his lack of prospects. He never visited Israel. The book was finished posthumously. I wonder if it would have been different if Pekar had more time to work on it. As it is, the book is neither a very successful graphic essay nor a moving autobiography.

Of course, not all of the books about the Middle East follow this autobiographical, socio-historical trend. For example, there are two fictional tales of the metropolitan city of Cairo, which became a focus of political interest again after the 2011 Egyptian protests: the not so successful Cairo (2007) by G. Willow Wilson and M.K. Perker and Metro: A Story of Cairo by Magdy El Shafee. Published in 2008, Metro, deemed “the first adult Arabic graphic novel,” reflects the corruption and disintegration of the social system under the Mubarak’s regime. Reading it gives us an uncanny sense of the coming Arab Spring. Not surprising, the English translation came out in 2012, which may have more to do with interest in the Arab Spring than the quality of the book.

Habibi (2011), similar to The Sandman #50, is a beautifully rendered work by one of the most important graphic novelists, Craig Thompson. While the works on Israel and Palestine are often criticized for being politically biased, Thompson’s graphic novel is controversial because of its Orientalist approach. There is even an online roundtable. Both Gaiman and Thompson are of course aware of what they are doing. Which bring us back to the other common narrative of the Middle East, the one embedded in the retelling of The Arabian Nights.