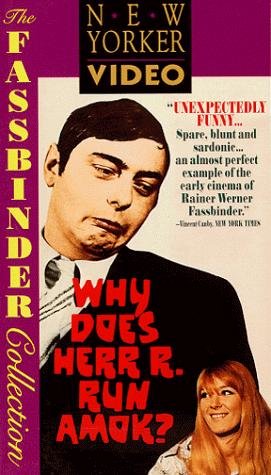

“The most disgusting film I ever made.”

Rainer Werner Fassbinder on Why Does Herr R. Run Amok?

When I was an undergrad at Santa Clara University, I took buses to San Francisco to see foreign movies. I remember rushing into a double-bill of New Yorker Films. During the first movie, Why Does Herr R. Run Amok? (1970), I had to go to bathroom. I thought nothing important is going to happen, so I went.

Why Does Herr R. Run Amok?, co-directed with Michael Fengler, is Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s first color movie, but the atmosphere is mute and monochromatic. The camera work switches between long static shots and jerky handheld takes. The scenes can be uncomfortably long. The conversations are improvised and natural like John Cassavetes’ films. The characters are named after themselves. Kurt Raab has the Kafkaesque name Herr R.

This documentation of a petite bourgeoisie family is like a reality show that is not edited for drama and entertainment. It records the ordinary and mundane middle-class. Kurt Raab works as a draftsman in an architectural firm. His stay-at-home wife mainly focuses on having parties, worrying about her status in the neighborhood, and her husband getting a promotion. She doesn’t spend much time solving the problems of their son in school, and her idea of dinner is bread and cold cuts.

The couple spends their time at vapid gatherings, with often dull and trite conversations. The back jacket of the fantoma released DVD explains, “A middle-class German, leads a life of boredom and quiet desperation. Between the blandness of his job and the disappointment and frustration of his family life, Herr R. can find no peace.”

Kurt Raab is often alienated, marginalized, and withdrawn in the social gatherings. When he tries to speak and give a toast during the Christmas party, it turns to a disaster. His boss refuses his drunken toast and his wife reprimands him says, “The older you get, the more stupid you become, and fatter. Even the neighbors are talking about it.” She continues, “At home you can’t find your tongue and here you don’t stop talking bullshit!” I also remember the irony of the other scene where he is animated while reminiscing with a classmate. The scene ends with Raab singing their old hymn, “Oh, where am I to turn when grief and pain oppress me?”

By the end of the movie, the packed theater was almost empty. Only a dozen of us remained to hear one of the more banal conversations, in which a neighbor explains to Raab’s wife how she made her boyfriend jealous by flirting on their ski vacation. Then what should have been obvious from the film’s title comes to catch us by surprise. Raab, who has been trying to watch TV during their conversation, takes a candlestick from above the TV, lights the candle, and bashes the head of the neighbor. Next, he strikes down his wife with a blow and goes to his son’s bedroom and kills him. He then returns to the living room and turns off the TV, which is playing the song “Stand by me,” cutting off the phrase, “When the night has come, and the land is dark . . . ” The next morning at work, after his co-workers deny to the police their ever having socialized with him, they find Kurt Raab hanging dead in the bathroom.

What is so shocking about the ending isn’t the actual murders. It’s the result of what Nick Pinkerton from Reverse Shot calls “a relief from the eighty-odd minutes of psychic violence that preceded it.” Apparently all the people who had left the theater felt the same. His mundane life was too painful to watch. The audience had killed him long before he followed their lead. And I was complicit in having gone to the bathroom thinking that his life was forgettable.

Fassbinder makes us think about our own ordinary lives. He allows us to experience the force of pure cinema. If it is too painful to watch, is it too painful to live? I never forgot the experience of watching an ordinary life become extraordinary. You have to go through the experience to be haunted by it. Emily Dickinson says, “If I read a book [and] it makes my whole body so cold no fire ever can warm me I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only way I know it. Is there any other way”?

Another director who made me experience a similar visceral sensation of pure cinema was Chantal Akerman—also a 25-year-old LGBT director. Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxeille (1975) is a different film, made by a woman about a woman and a landmark of feminist cinema. But there are also great similarities. Both movies focus on a main character whose name is emphasized in the title. Again we have a movie with a shocking ending that challenges us through the viewing experience of the everyday life. In both movies the directors only record activities of their characters, avoiding explanations or the psychological traits. These films are dark meditations on the quotidian lives whose surface once broken will shatter the world and haunt us.

A few years later, when I was studying at University California, Santa Cruz, we drove up to San Francisco to watch Jeanne Dielman. The audience this time was more receptive, though Akerman describes people leaving the theater in its first showing at the Cannes. I was also more prepared for the slow foregrounding of the domestic work. Akerman, by choosing a leading French actress, Delphine Seyrig, prompts us to concentrate on the everyday work of a woman. But nothing prepared me for the consequence of rupture in the contained ordinary life.

Akerman uses a wide-angle lens and a fixed camera that is set at a waist-level, framing Dielman in a symmetrical picture, which she often enters and exists. These are long takes. Instead of the improvisatory style that Fassbinder uses, Akerman takes a formalist approach, inspired by Michael Snow’s Wavelength and La Région Centrale. And she goes a step further, adding the narrative and emotional resonance. She turns the suspense in the formal exercise of repetition and variation into something more–an existential revelation. The movie becomes a new way of engaging traditional themes, such as the role of women as caring mothers or sexual objects or whores.

The film begins with documenting the daily routines of Dielman, which–with the exception of the visit of a john who leaves her bedroom giving her money–are ordinary, uneventful, and unemotional. We are drawn to the obsessive way in which Dielman structures her day, a compartmentalization that enables her to control and contain her emotions. There is a great deal of care in the depiction of her ordinary life.

After the visit of a second john on day two, a chain reaction starts. With small gestures, the ordinary and familiar routines are broken. She forgets to put back the lid of the soup bowl where she keeps her money. She forgets to turn off the light. She cooks the potatoes for too long, and frantically tries to figure out what to do with them. We begin to sense her anxiety watching Dielman enter and exit the frames as if she is breaking out of the containments of hallways and doors. There are now more dark scenes and more cuts.

But as much as she tries, she can’t return the order. I remember, during the third day when she put a dish in the drainer with soap bubbles still running down, everyone in the audience gasped. The ordinary turned to the extraordinary. We can’t look at the mundane daily routines in the same way anymore. We don’t need the roller-coaster ride of Hollywood blockbusters to feel the suspense and be spellbound. From now on every switch of the light is a passage between light and dark, between order and chaos.

We look for clues. Did something different happen in the bedroom with the second john? Did she stay too long? Did the last night’s conversation with her son about how she met her husband trigger it? The son Sylvain said to her, “If I were a woman, I could never make love with someone I wasn’t deeply in love with.”

The second night’s conversation with her son goes a step further. He admits to being frightened by the description his friend gives of the man’s penis being like a sword that thrust deep into a woman. He repeats the conversation to his mom, “What? Dad does that to Mom? I hated Dad for months after that, and I wanted to die. When he died, I thought it was punishment from God. Now I don’t even believe in God anymore.”

During a third john’s visit, we are allowed into the bedroom, watching Dielman as she undresses, not knowing he is also watching, until we hear his cough. We then see her try to free herself from underneath him. We watch the signs of pain and pleasure that seem to end in an orgasm. Akerman in the interview on the Criterion DVD says that Dielman had her first orgasm with the second john. The recurrence is now an omen of permanent rupture. The repressed emotions can no longer be contained. As she dresses, Dielman glances at what looks like her and her deceased husband’s photo on the dressing table, picks up the scissors (a domestic household tool) from behind the picture and stabs the third john in the neck.

Unlike in Fassbinder’s movie, however, Dielman doesn’t kill herself. Instead she sits at the dinning table with blood on her hand and on her white shirt near her heart. We stare in silence at her subtle display of different emotions in the semi-dark for seven long minutes. We wait for the new era that this fissure of the ordinary life has opened. I recalled how Emily Dickinson began her poem:

My Life had stood – a load Gun –

In Corners – till a Day

The Owner passed – identified –

And carried Me away –