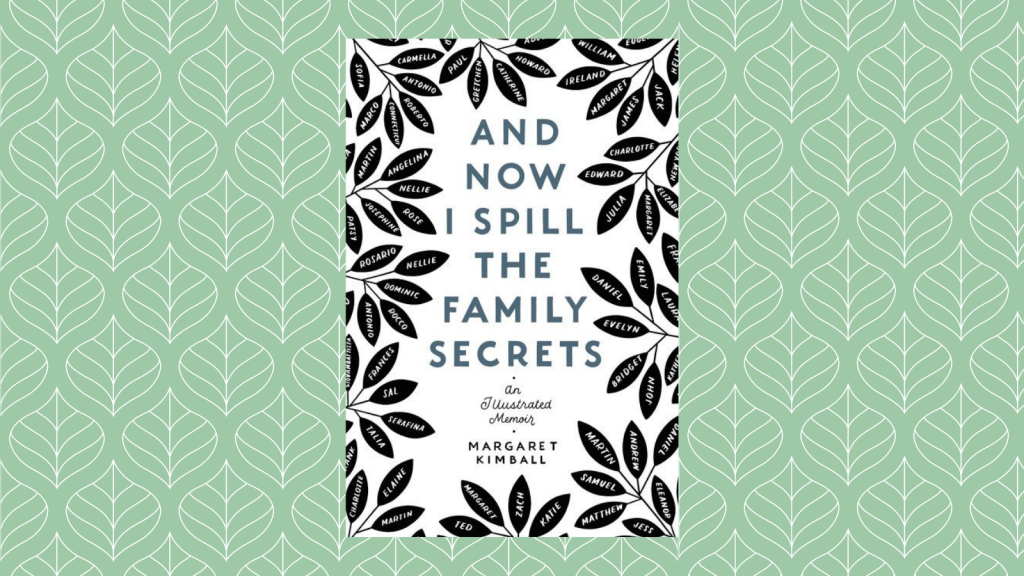

Margaret Kimball is an award-winning illustrator and the author of And Now I Spill the Family Secrets, a graphic memoir about mental illness and family dysfunction.

Her graphic essays have appeared or are forthcoming in The Believer, Ecotone, Black Warrior Review, South Loop Review, and elsewhere. Her work has been listed as notable in Best American Comics. Her hand lettering and illustrations have been published worldwide, and she’s worked with clients like Smithsonian Magazine, Macy’s, Boston Globe, Little, Brown, Simon & Schuster, Diageo, Ogilvy, Random House, and many others.

Born in New England, Margaret studied illustration at the University of Connecticut. She has two MFA degrees from the University of Arizona, one in creative writing and one in illustration. She was a Sarabande Writer-in-Resident at the Bernheim Forest, and she’s also been in residence at Yaddo and MacDowell.

Her debut graphic memoir came out on April 20, 2021, and she spoke to M.D. McIntyre about the process of writing a beautifully illustrated book about mental illness and her family, and of course, spilling all the family secrets.

M.D. McIntyre (MDM): It is so great to talk to you about your book. I felt connected to your memoir in so many ways. I also grew up in the 90s, and so many of those moments from your youth resonated with me and made me laugh out loud. But I also have many people close to me who struggled with mental health issues. I’m really curious about what sparked the project for you?

MK: It’s interesting because I was asking myself this question a few years ago too. I was putting the whole first draft together. I pointed to the phone call from my brother when I was nineteen when he first told me about my mom’s suicide attempt in 1988. I think that rattled me. I thought, what other secrets are these people hiding? What does all this mean?

But honestly, when I read my diaries from when I was ten years old, even at that point, I was saying things like, “My life is fit for a book; it is so crazy.” I didn’t say any specific thing that was crazy, which is, of course, really funny. But I always had this sense that I was going to document my life somehow. I was kind of always taking notes from my life and thinking about it in terms of a book. The process took, I don’t know, fifteen years longer than I imagined it would. But I think it was that phone call from my brother that sent me on this journey about these secrets in our family.

MDM: Is there a point where you knew that the book would take this form, a graphic memoir? Did you know that from the beginning?

MLK: I did, sort of. In college, I was writing essays because it never occurred to me that I’d be allowed to hand in my pictures for my English classes, so I would write essays. But once I got to grad school, my project was always in graphic form. It changed over time, how it looks, but it was always drawing and writing together.

I don’t think I could have done it any other way because it is my way of thinking and processing. Whenever I write, I always start by just writing alone and trying to get the story good enough by itself. Even when I think, “Wow, this is a publishable piece,” it just feels empty to me if there aren’t pictures in it. So, after I wrote an essay, then I would go back and put in pictures.

MM: Were you an artist first?

MK: I did start in the art department. I love to read, and when I was in college, I decided to minor in English. There was an autobiography class, and it sounded interesting to me. I ended up reading about six or seven memoirs and a bunch of essays, and I just fell in love with it. I thought maybe I can learn to write. When I got to grad school, I was in the Visual Communications program first. I started taking some writing workshops. I kind of weaseled my way into the classes, but then the professor asked me to join the program. I got in, but I started in the art program, and the writing program always felt secondary because I joined it later.

MDM: Do you feel like the illustrations are a reflection of your style? Did you know that the illustrations would always be black and white, or did you ever consider adding color?

MK: It’s definitely a reflection of my style. I’ve spent my whole life trying to loosen up my drawings. I can do it, but I always tighten them back up. So it’s funny. It’s like I want to buy art for my house or something, and I love loose drawings, but I can’t do it myself. I don’t know if there’s some anxiety in me or something, but I always get rid of those drawings and tighten them.

As for color, it is always so foreign to me. I can’t figure it out. I love colorful things; well, I say that and then I look around and my entire house is black and white. So I guess black and white is my favorite combination—I think because it’s so stark. But I wanted the illustrations in the book to feel rich. When I had just black and white drawings, I was having trouble. I decided to put the washes in to give them a visual richness and depth. And to allow for some depth of field. For example, with the trees, the washes helped create a foreground and a background.

I thought for a while I would do a wash with color like Alison Bechdel has in her memoir Fun Home. She has a blue wash while the rest of the book is black and white. But in the end, I never thought color looked right to me for my book. My daughter said, “You know everyone hates black and white, right? You know color is so much better?”

MDM: That is hysterical! I’m with you, though; I love black and white. Especially pen and ink drawings, I’m just drawn to it. Did you draw inspiration from anyone else’s stories when you were putting your book together? Were there certain artists or authors who inspired how you presented your story?

MK: Totally. Mary Karr is a huge influence. I love Marjane Satrapi. You know, there are some fiction writers who write amazing memoirs, like Elizabeth McCracken has a beautiful book, An Exact Replica of a Figment of My Imagination, and Kevin Brockmeier’s A Few Seconds of Radiant Filmstrip. You know, one interesting thing happened when I was getting into the investigative aspect of the book where I was trying to finalize documents and interview everybody, and I was trying to figure out how to build momentum. Then I read a memoir called Five Days Gone by Laura Cumming. It was just riveting. The story itself is basically that her mom disappeared for five days when she was a child, and the author goes back and tries to figure out what happened. She just went back to the town where her mom grew up, interviewed everyone, found every public record, and recorded every police record. I was just riveted with her process of trying to uncover the truth of what happened. Reading that helped me shape the book. I wanted it to be a little bit like an investigative piece, where I asked every question I could ask and found every document I can find. I think specifically in terms of the craft and shape of the book, that was a huge influence.

MDM: I love it when you find that essay or book that has the form you need.

MK: I feel like when you’re working on something, and then you find a book or an essay that does what you’re dreaming of, it’s just magical. I love that kind of puzzle, getting it to take a shape.

MDM: I think there’s a history in your book has that is so interesting. It seems like a unique moment for the discussion of mental illness in our country, and your book has a historical look at those issues, as well as a present look at how we could talk about mental illness. Did you know you were doing that?

MK: The book went through so many phases, and I spent a long time reading about the history of mental illness at one point. But then I realized, I’m not a historian, and I’m not a scientist. I’m not ever going to likely understand the workings of the nervous system or whatever. I just had to write my narrative. But I had read a lot about it and thought about how we treat people in our society with mental illness: how they are marginalized, and there is so much stigma around mental illness, and obviously, there are better ways to do things. I wanted to look back within my own family and try to understand my grandma’s experiences and my mom’s in relation to growing up with her mother. Then look at our experience with my mom, and then, of course, my brother. I tried to focus on the generational aspects within our own family history. But having said that, at different points in the book, I was reading books on mental illness, like at one point I was reading Foucault’s Madness and Civilization. I did an independent study in grad school on the history of mental illness and just read so much, so I feel like that’s just kind of in me, little bits and pieces of what societies have done over time.

MDM: Did you have an audience in mind when you were writing?

MK: It is a book that I would have wanted. Which made me think there must be people who go through this situation, where weird things are happening, and no one is talking about it. You get a diagnosis, but when you’re ten years old, what does bipolar mean? No idea. You know, for the entirety of my childhood, everyone says, “Oh, your mom gets sick sometimes, and you don’t need to talk about it to anybody. It’s nobody’s business.” I just wondered if I was crazy or I was not seeing things right. I always wanted someone to articulate things and say: This is what is happening. This is what it means. This is where your mom is at. But nobody else wanted to do that. I just thought it would give comfort to somebody experiencing a family member having trouble, and it is getting swept under the rug. So they can read something that says that situation is worthy of talking about and worthy of bearing witness to. I did hope my book could help people in that situation.

MDM: That seems important. One of my favorite scenes in the book is when you openly talk to your brother about what he is experiencing; it felt like someone bearing witness to his experience was so important in a scene.

I’m curious if you have thoughts for other writers about what it looked like going from completing your degree to the point where you were talking to your editor. For a lot of people, it is such a long road. What was that like for you?

MK: Everybody has a different path. I went into the program wanting to write a memoir, but my program is all about the essay. I think a lot of nonfiction programs are, and my program was really into lyric essays. I got swept up in this. I stopped reading memoir, and I was reading all these lyrics essays, but I was never really working on the craft of clear narrative. Because it was considered traditional and kind of boring. I think that derailed me for a long time.

It was a few years after I graduated when I realized I need to go on my path. Basically, I had to find my way back to memoir. Everyone talks about essays—they can be so smart. But it wasn’t for me because it is too much on the surface, too much façade. I just wanted to write about the mental illness in my family. I wanted scene, and I wanted dialogue. So I just had to let go of that feeling, that sense that I had to write essays to be smarter or had to write essays to please my mentors or be a part of my community. I wanted clear, descriptive stories. Mary Karr is a perfect example. I love all of her work. Once I finally just let go of whatever I’ve been studying and reading in grad school, it was much easier.

At the end of grad school, what I had was a collection of essays—or whatever it was. It was just sort of a mess. But later, I got a residency at MacDowell and literally just spent two weeks writing. I made a full draft of the book. I mean, I had a lot of passages written, and then it took two years after that to get it in good shape for editors. I think that determination— I’m going to sit down and write to start to finish—and then forcing myself to find the time and space to do that was integral to the book happening.

MDM: I think it is wonderful for people to hear that. Especially the people pleasing aspect of writing for others—our mentors or a program—it certainly resonates. We think a lot about what people like or what they want, and sometimes that is not what we want to do with our work.

MK: Some of the best advice I got was from Charles Bock, who said the publishing world will be there, don’t rush your book. It was so good to hear that because good writing is good writing.

MDM: Are you working on another project right now?

MK: Yes. Well, I was planning never to write a book again, because it’s a miserable process in many ways! Though I do love my book. But it turns out I am working on another book about my relationships. It is sort of a book about therapy or about the therapy I’ve gone through to work through some of my history. So I’m writing and reading about therapy. Have you read Laurie Gottlieb’s Maybe You Should Talk to Someone? It is so good. And I just read Christie Tate’s Group: How One Therapist and a Circle of Strangers Saved My Life. Both of those were riveting.

MDM: I think that I think that so relatable. There are these moments in therapy when you’re going through all these various processes, and I think those reflective passages in a book or ‘ah-ha’ moments are relatable to readers.

MK: Yes! I love therapy books.

MDM: Well, thank you so much for chatting with me; I can’t wait for everyone to see your book.

MK: It was great to talk with you, and I appreciate you reading the book and chatting with me about it.