The shadows were thick behind the fence: in the dry transparent air, even more transparent monsters were roaming around. I didn’t need to become a wandering tree; I only needed to stay here and wait for a certain change to occur. Change truly did begin.

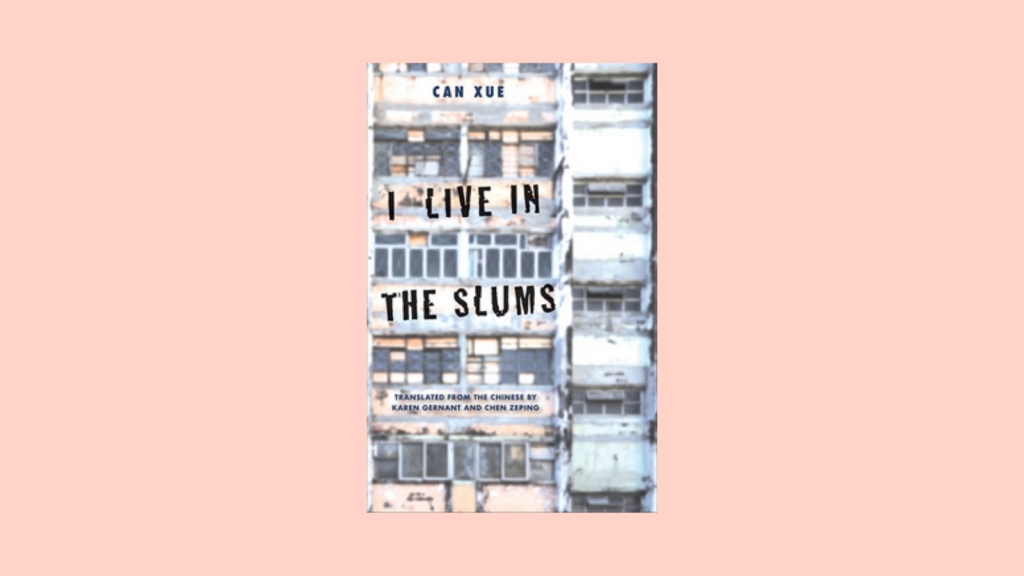

At the end of what was arguably the strangest, most isolating year in recent memory, the experience of reading I Live in the Slums by renowned master of avant-garde literature Can Xue was a little like looking into a distorted mirror that reflected a certain lingering agitation. In her newest collection (translated from the original Chinese by Karen Gernant and Chen Zeping and published by Yale University Press in May 2020), Can Xue has written into existence a dark clutch of nightmare worlds that embrace the stifling nature of society while remaining gorgeously expansive. Characters fight to understand their own purpose. They are isolated in the midst of teeming crowds. They struggle to find joy when they are just trying to survive. Much like 2020, the characters and stories in I Live in the Slums feel disorienting and hauntingly familiar at the same time.

During an interview with Dylan Suher and Joan Hua for Asymptote, Can Xue (a pseudonym for Deng Xiaohua) stated, “Every reader must stand up and perform in order to enter the realm of experimental literature.” In I Live in the Slums, however, it is not only readers who are required to cross the threshold; characters, too, must make these risky leaps to truly feel alive. Two little boys long to venture over a partition between a communal kitchen at midnight only to enter a seemingly alternate reality full of invisible cooks. A young man devotes his life to transcending his ancient city to experience even a moment inside the fabled swamp beneath it. A married magpie couple journey from the safety of their nest built in a waving poplar tree to visit the empty shell of a human house in which they had previously watched the inhabitants burn to death. In each of these stories, Can Xue’s often hallucinatory twists of plot and character demand that both protagonists and readers reassess our understanding of the world and what we are willing to do to be part of it.

Much is made of the way Can Xue experiments with form and structure; the book jacket on my copy, for example, explains her “stories observe no obvious conventions of plot or characterization.” For the uninitiated, this unique style can result in a befuddling reading experience—one that requires readers to double back again and again to check the meaning-making the author has parceled out in crumbs along the way. How does “Story of the Slums,” the 85-page novella at the start of the collection, change if we decide that the narrator is a rat as they are frequently called, or maybe a dog (slightly more likely), or perhaps a ghost, or even a metaphor for a city’s impoverished citizens? Perhaps they’re all of these things and more, and maybe that’s exactly the point. If you’re looking for an easy out, you won’t find it in Can Xue’s writing. Sometimes it’s enough to make a reader question their ideas and abilities, but this, the author argues in the Asymptote interview, is exactly the point. “If the eyes of the readers are open, and their curiosity is piqued,” she says, “they may become eager to add their own interpretation to the work they are reading, or even to the fiction that they themselves write.”

Whether characters fear both a sinking pit beneath their bed and the impending destruction of their neighborhood, they are lost inside an abandoned building whose floors and support beams shift like a kaleidoscope, or they are haunted by spectral swamp piglets, the invisible character in each story is bewilderment. The protagonists never feel quite at ease; menacing shifts to reality erode their self-confidence, and no one ever knows who they can trust. This instability has the counterintuitive effect of allowing readers to sink deeper into Can Xue’s stories because it allows us a kinship with the characters as they live out our bewilderment on the page. This meta, Neverending Story-like experience has a way of inducing familiarity even amid otherwise surreal landscapes and experiences.

The narratives in each of the 16 stories in this collection vacillate between the micro—insects, rodents, birds, plants, and the macro—life, death, civilization, humanity. Can Xue’s prose, too, vacillates between playful turns of phrase and deadly serious subject matter to provide a constantly shifting narrative experience. At times, it can feel almost overwhelming, but if you read on long enough, you’ll get satisfying little jolts of recognition as the same characters, images, and themes pop up across the collection. In “The Outsiders,” for example, one of the last stories, a child named Daisy interacts with the “rat” from the first story. In “The Outsiders,” however, the creature is described as “a plump little animal crouching on the massive tombstone to her right. It was pale red, and its skin was so thin that it was transparent.” Later, Daisy notices, “Its head was wrinkled, sort of like an old man’s.” Then, perhaps most baffling, “the expression in its eyes made Daisy think of Dad.” Daisy can’t quite decide what to make of the creature, and so she can’t help but obsess over it, longing to hold it in her arms and understand just exactly what it is. Daisy, like us, cannot look away.

So, what to make of a collection that is at turns confusing and deeply engaging? What happens when we find ourselves face-to-face with a 13-year-old girl in love with her Venus-obsessed cousin or an elderly cicada cantor who lacks an audience when his voice turns from joyful to agonized? I’ll posit that while our task as readers of this collection occasionally veers towards burdensome, it is far more often exciting. After all, how frequently are we invited not merely to read and enjoy, or to read and wonder, but to read and examine? To read and clarify? You could spend time trying to fight against the weirdness of these stories, but it’s significantly more satisfying to wade into the often unsettlingly beautiful universe Can Xue has created until you are swimming in it, your head beneath the water; only then will your submersion be complete.