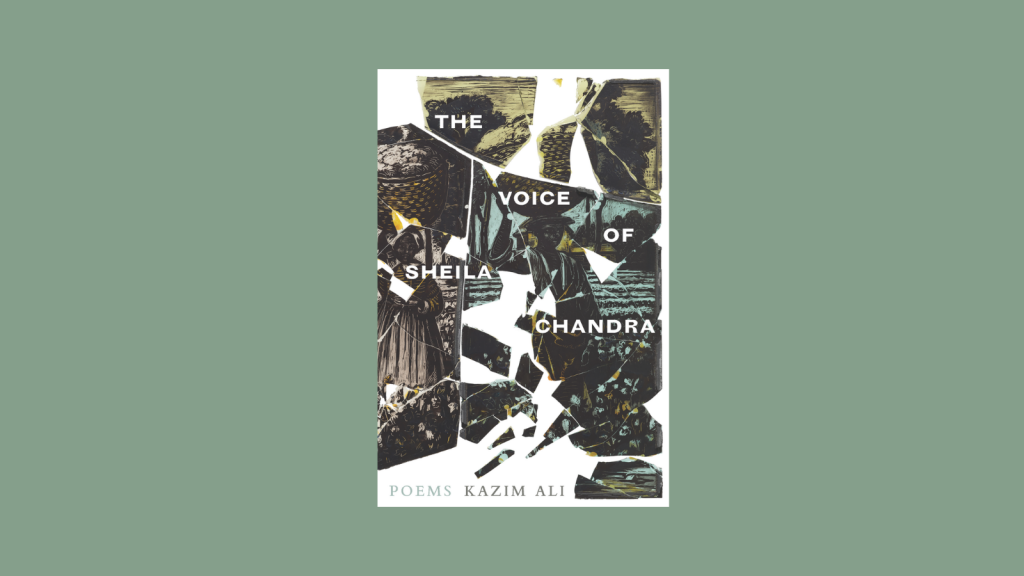

The Voice of Sheila Chandra, Kazim Ali’s latest collection, profoundly sings. The music in this book is generated by a constellation of fellow artists and history makers that Ali has gathered across time and space. God is included, too, in this choir; Ali’s opening invocation, “Recite,” sets the tone: “God’s like you a misfit / You don’t fit he don’t fit.” To name just a few of the holy misfits we encounter, there is Corey Menafee, the former dining hall attendant at Yale, who broke a stained- glass window depicting images of enslaved Africans picking cotton, and Sheila Chandra, an experimental pop vocalist, who had to abruptly stop singing due to a rare condition called burning mouth syndrome. This book is also formally daring, orbiting around three long poems: “Hesperine for David Berger,” a thirteen-page lament against violence and injustice; “The Voice of Sheila Chandra,” a forty-part sonnet sequence summoning Chandra’s voice; and “Phosphorus,” which slides from free verse into a puzzle of letters, inviting readers to participate in a translation-like process.

Ali’s “Hesperine for David Berger” gives necessary lyricism to feelings of sorrow and rage. Curious about what a hesperine might be? It is a free-verse form that Ali has invented. Within the body of the poem, a hesperine is described as “not a serenade nor an aubade but rather a curse to first darkness itself begging it not to fall.” It is also a poem “to ward of death.” The music Ali achieves in his hesperine is best described as symphonic given the poem’s sweeping thematic range – confronting violence caused by nationalism, Islamophobia, Antisemitism, and white supremacy; connecting bodies across time and space; and defying death and night. Here is a sampling of one of the more heated moments of this curse before nightfall:

Sun is going down on the wrong horizon, the sea glows green then blue then green again this where I was born this in-between place

And so I curse this fucking dawn that grinds men to powder tears them from their bodies flings them down the hot dark barrel of a gun

In these lines, grief hits our ears and shifts to rage. There is a leaden weight in the long “o” that recurs in “going down” and “wrong horizon,” which is interrupted by a high-pitched cry, the “i” in “this” and “flings.” Fury is also not withheld in the hard “c” consonants of “curse” and “fucking.” Sitting with Kazim Ali’s hesperine took me back to Audre Lorde’s essay, “Uses of Anger: Women Responding to Racism.” Notably, in this piece, Lorde says: “Anger is information and energy.” She illustrates how the anger of women, particularly the anger of women of color, can lead to radical insight. While the specific contexts igniting Audre Lorde’s and Kazim Ali’s work are different, their passions for justice and self-reflection run parallel. I am struck by how the speaker of “Hesperine for David Berger” uses the energy of anger to search for meaning. Notice how the previously mentioned excerpt is followed by these stirring lines of inquiry:

How then to catalog the metadata of all the corpses that locate for us our own bodies and register their Western comfort

Bullet punching through a body like punching through a ticket registering it for passage

Do you know god is what’s not do you know what art is what’s not do you know what a nation is a citizen a crime

The speaker’s anger leads to a spiral of questions and a critique of “Western comfort.” Throughout “Hesperine for David Berger,” thoughts collide at a fever pitch amplified by the poem’s lack of punctuation. But in moments of introspection, such as the one above, an absence of punctuation subverts syntax, upending the meaning of words. Ali blurs where some questions begin and end. The effect of this slippage is an interrogation into what God, art, and nationhood are and are not.

Another standout moment in this poem is when the speaker compares Corey Menafee’s shattering of stained glass with a broom to singing. Especially poignant is the enjambment after “he” and before “sang,” which emphasizes Menafee’s embodied response to the legacy of white supremacy in his workplace:

What Corey Menafee did is he climbed up on top of a table in the dining room and with the long handle of his broom he

Sang in bits and pieces to god the road you knew which was the confusion road the one made of all your wrong turns

By describing Menafee’s action as singing, Ali suspends and elevates this moment in time, as the act of singing a song is slower than the act of breaking glass. Also, by comparing Menafee’s action to singing, Ali conveys the beauty in decisively acting on one’s outrage. In the retelling of the moment, the speaker clarifies that what is violent is the oppressive, racist imagery looming in stained glass, not the choice to disrupt this imagery with a broom. The split-second during which Menafee acts is one that the speaker returns to across the poem. By returning to this instance, the action becomes a powerful refrain, such that the mere mention of shattering or glass in the poem invokes Menafee’s revolutionary song.

Corey Menafee is just one remarkable figure in Ali’s poem. Throughout “Hesperine with David Berger,” Ali disrupts and bridges the time-space continuum by placing disparate lives and energies side by side. For example, the poem aligns two athletes of different decades, homeplaces, and religions. We visualize Mohammed Al-Khatib, the Palestinian sprinter with Olympic dreams, in Ramallah in 2016 training without “spikes nor coach nor starting blocks,” while simultaneously visualizing David Berger, the American-Israeli weightlifter, dying during the massacre at the Munich Olympics in 1972. At one point, the speaker declares, “These boys’ bodies are particles of light that travel one into the other.” A diction of connection and possibility illuminates the poem, as the speaker invites us to imagine potential intersections between lives, bodies, and particles. Ultimately, Ali’s hesperine generates a transformative logic, where grief, rage, and inquiry garner enough energy to shatter time, open portals, and remap history:

What sounds breaks the circle of action and reaction If space do bend then time Can history be unwoven the tightness released to make it possible to breathe and write anew Are we pieces made up of pieces made up of pieces

The title sequence, “The Voice of Sheila Chandra,” explores the breaks that occur in the artmaking process. The poem considers breaks as crisis moments where no sounds come and breaks as threshold spaces between boundaries. There is a moment in the 9th sonnet when the speaker says, “You do not want to say but sing,” implying that singing grants access into that which feels unsayable. Each sonnet moves athletically down the page, engaging our mouths in a conscious consonant and vowel workout. In the opening lines, language rushes and eddies off our tongues:

Breaks is constant was like The river light on the river Riven that remained a rift An old rill that sounded She merged with the vibe

Throughout the poem, there is a sense of continuity between Sheila Chandra and the poet-speaker, a feeling of fluidity between their voices. In fact, it is as if the speaker has picked up a baton of song that was handed off by the pop singer and found his own: “Chandra/ Lost her voice around the same/ Time I found mine at midnight.”

As the poem progresses, the speaker sings explicitly at the boundaries of faith, gender, language, and speech. These threshold spaces carry some of the poem’s most engaging sonic collisions:

Is the voice to know or to know The edge of knowing Muslims do not Depict or particularize God only gesture With blank spaces Ali Kazim does not Paint with a brush but pounds powdered Pigment right into the paper he compromises Masculinity by picturing a muscular Man with a flower tucked behind his Ear shaving himself with a straight razor He reinvents manhood as a form of The feminine texture of a voice breaks in 2007 I saw a Catalan Antigone and at the moment Of her incomprehensibility the actress began Screaming in English

As the speaker challenges normative masculinity in the sonnet above, a plosive consonant “p” pulses through the diction: “pounds powdered / Pigment right into the paper.” The absence of punctuation also contributes to a sense of flux. When the “texture of a voice breaks,” the voice could be that of the speaker reinventing manhood or that of the actress screaming in English during her multilingual performance.

Singing versus saying also leads to unexpected diction, such as when Ali writes, “What represses unhomes in the sound.” What does it mean to unhome? We can’t be certain. But the word “unhomes” makes intuitive sense when naming a break with repression. The word vibrates in the mouth, generating energy, as the resonant “n” and “m” consonants reverberate. The notion of breaking with home also leads to questions of origin:

What represses unhomes in the sound Who has made me what is made me Is a voice just muscles and shape and Breath to phrase a song boats assemble At the mouth of the harbor mouth in Earth you who wrote an ode to silence Never wrote of what is silenced I did

Again and again, the speaker in this poem returns to the home that is the body, fundamentally trusting the voice made of “muscles and shape and breath.” Guided by boats at the “mouth of the harbor mouth,” Kazim Ali breaks silence and writes silence into song.